When I want to emphasize a point on criminal justice reform, I lead with the data. There are huge racial gaps in arrests, convictions, and sentences. I’m shocked by the statistics and assume that’s also true of readers.

But according to a new study from Stanford University psychologists Rebecca C. Hetey and Jennifer L. Eberhardt, the stats-first approach to issues of race and incarceration isn’t effective—in fact, it’s potentially counterproductive.

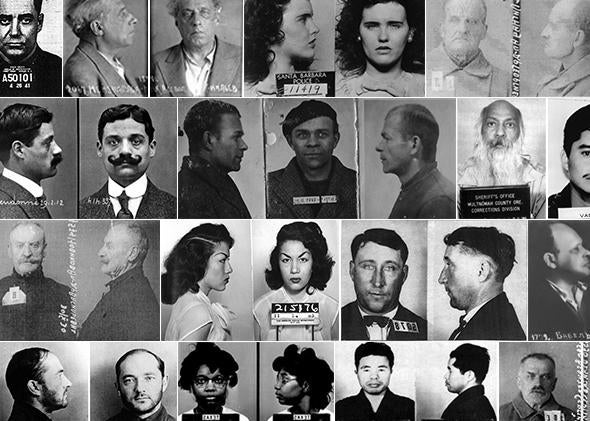

Hetey and Eberhardt conducted two experiments, one in San Francisco and one in New York City. In the former, a white female researcher recruited 62 white voters from a train station to watch a video that flashed 80 mug shots of black and white male inmates.

Here’s where it gets interesting.

Unbeknownst to the participants, Hetey and Eberhardt had “manipulated the ratio of black to white inmates, to portray racial disparities in the prison population as more or less extreme.” Some participants saw a video in which 25 percent of the photos were of black inmates, approximating the actual distribution of inmates in California prisons, while others saw a video in which 45 percent of photos were black inmates.

After viewing the mug shots, participants were informed about California’s “three-strikes” law—which mandates harsh sentences on habitual offenders with three or more convictions—and asked to rate it on a scale of 1 (“not punitive enough”) to 7 (“too punitive”). Then participants were shown a petition to amend the law to make it less harsh, which they could sign if they wanted.

The results were staggering. More than half of the participants who viewed the “less-black” photographs agreed to sign the petition. But of those who viewed the “more-black” photographs, less than 28 percent agreed to sign. And punitiveness had nothing to do with it. The outcome was as true for participants who said the law was too harsh as it was for those who said it wasn’t harsh enough.

In which case, Hetey and Eberhardt hypothesized, there must be another explanation. Hence the New York City experiment, which tested the role of fear in driving support for harsh law enforcement policies. There, they found similar results using a variation on the San Francisco test.

Instead of photos, researchers gave demographic statistics on New York state’s inmates to a sampling of 164 white adult New York City residents. As with the previous experiment, one group received a “more-black” presentation—where the prison population was 60.3 percent black and 11.8 percent white, approximating the racial composition of inmates in New York City jails—while the other received a “less-black” variation, where the prison population was 40.3 percent black and 31.8 percent white (approximating that of the U.S. prison system writ large).

Next, participants read that a federal judge had ruled NYC’s “stop-and-frisk” policy unconstitutional, and they were asked to answer several questions: “Given the ruling, how worried are you that crime will get out of control without the stop-and-frisk program?”; “How comforted were you knowing that people were being stopped as part of the stop-and-frisk program?”; “To maintain safety, how justified is it to use stop-and-frisk tactics?”; and “How necessary is it to have the stop-and-frisk program in place to keep crime low?”

After questioning, researchers gave participants a sample petition calling for an end to stop and frisk and asked them the following question: “If you had been approached by someone and asked to sign a petition like the one you just read, would you have signed it?” They had a choice of “yes” or “no.”

Again, participants in the “more-black” group were significantly less likely to endorse the petition (12 percent) than those in the “less-black” group (33 percent) even though most saw stop and frisk as a punitive measure.

The researchers also found that “crime concern” affected the willingness to sign the petition, as they wrote in their paper: “The more participants worried about crime, the less likely they were to say they would sign a petition to end the stop-and-frisk policy.”

Taken together, the conclusion was that “exposing people to extreme racial disparities in the prison population” led to a greater fear of crime and—at best—an unwillingness to support reform. For as much as you might be outraged by the vast racial disparities in marijuana arrests, for example, the general public might see the image of a young black man and hunker down in its support for marijuana prohibition.

It’s disheartening. But, if I can indulge my cynicism for a moment, it’s also not too surprising. From previous research, we know that—among white Americans—there’s a strong cognitive connection between “blackness” and criminality. “The mere presence of a black man,” note Eberhardt and other researchers in a 2004 paper, “can trigger thoughts that he is violent and criminal.”

Indeed, they continue, simply thinking about black Americans can lead people to see ambiguous actions as aggressive and to see harmless objects as weapons. When Michael Dunn saw 17-year-old Jordan Davis and his friends, he perceived a threat, imagined a gun, and opened fire, killing Davis. “I was the one who was victimized,” said Dunn in a phone call to his fiancée before his trial. It’s ludicrous, but it’s not dishonest. Like many other Americans, Dunn sees black people—and black men in particular—as a criminal threat.

What’s striking is this goes both ways. “In a crime-obsessed culture,” says the study, “simply thinking of crime can lead perceivers to conjure up images of Black Americans that ‘ready’ these perceivers to register and selectively attend to Black people who may be present in the actual physical environment.” In other words, the connection between blacks and crime is so tight that just thinking about crime—irrespective of the environment—triggers thoughts of black people in the same way that thinking of black people triggers thoughts of crime. And if you want a more disturbing thought, consider this: In one of the 2004 experiments, researchers found that exposing police officers to crime-related words followed by photos of black inmates “increases the likelihood that they will misremember a black face as more stereotypically black than it actually was.”

On top of this, there’s the stubborn persistence of false or faulty ideas. “Misperceptions, like zombies, are difficult to kill,” writes political scientist Brendan Nyhan, citing the health care reform “death panel” myth, which persists five years after Sarah Palin pushed it into the mainstream. In fact, they’re so durable that giving counterinformation can strengthen the original misperception. Confront vaccine-skeptics with evidence that vaccines don’t cause autism, and they may respond with greater skepticism.

The dynamic between race, crime, and criminal justice reform is similar. Tell people that blacks are overpoliced and over-represented in prison, and it triggers thoughts of crime, which leads to fear, which causes a backfire effect as people follow their fear and embrace the status quo of unfair, overly punitive punishments.

The immediate takeaway is that advocates might want to try different language (or a different approach) in their campaign to reform the criminal justice system. Racial injustice might be the main problem, but that doesn’t mean it’s the problem the broader public wants to solve.

To go a little deeper, however, I think this study further underscores the extent to which “blackness” retains its racial stigma, even as we move far away from the time of explicit anti-black attitudes. The dramatic progress of the past 50 years hasn’t dismantled America’s racial hierarchy or reshaped its form. The mythical “war on whites” notwithstanding, black Americans remain a disfavored class, subject to negative stereotypes, residential segregation, and rampant police violence.

Not that there aren’t bright spots. Large communities of black Americans succeed and thrive in ways that weren’t possible a few decades ago. But ask yourself, during downturns and recessions, why are blacks the worst off? Why do they fall furthest? Is it some unique pathology? Or is the racial caste system—and our subconscious racial attitudes—more durable than we want to believe?