Last week, people around the world mourned the death of beloved actor and comedian Robin Williams. According to the Gorilla Foundation in Woodside, California, we were not the only primates mourning. A press release from the foundation announced that Koko the gorilla—the main subject of its research on ape language ability, capable in sign language and a celebrity in her own right—“was quiet and looked very thoughtful” when she heard about Williams’ death, and later became “somber” as the news sank in. Williams, described in the press release as one of Koko’s “closest friends,” spent an afternoon with the gorilla in 2001. The foundation released a video showing the two laughing and tickling one another. At one point, Koko lifts up Williams’ shirt to touch his bare chest. In another scene, Koko steals Williams’ glasses and wears them around her trailer.

These clips resonated with people. In the days after Williams’ death, the video amassed more than 3 million views. Many viewers were charmed and touched to learn that a gorilla forged a bond with a celebrity in just an afternoon and, 13 years later, not only remembered him and understood the finality of his death, but grieved. The foundation hailed the relationship as a triumph over “interspecies boundaries,” and the story was covered in outlets from BuzzFeed to the New York Post to Slate.

The story is a prime example of selective interpretation, a critique that has plagued ape language research since its first experiments. Was Koko really mourning Robin Williams? How much are we projecting ourselves onto her and what are we reading into her behaviors? Animals perceive the emotions of the humans around them, and the anecdotes in the release could easily be evidence that Koko was responding to the sadness she sensed in her human caregivers. But conceding that the scientific jury is still out on whether gorillas are capable of sophisticated emotions doesn’t make headlines, and admitting the ambiguity inherent in interpreting a gorilla’s sign language doesn’t bring in millions of dollars in donations. So we get a story about Koko mourning Robin Williams: a nice, straightforward tale that warms the heart but leaves scientists and skeptics wondering how a gorilla’s emotions can be deduced so easily.

Koko is perhaps the most famous product of an ambitious field of research, one that sought from the outset to examine whether apes and humans could communicate. In dozens of studies, scientists raised apes with humans and attempted to teach them language. Dedicated researchers brought apes like Koko into their homes or turned their labs into home-like environments where people and apes could play together and try, often awkwardly, to understand each other. The researchers made these apes the center of their lives.

But the research didn’t deliver on its promise. No new studies have been launched in years, and the old ones are fizzling out. A behind-the-scenes look at what remains of this research today reveals a surprisingly dramatic world of lawsuits, mass resignations, and dysfunctional relationships between humans and apes. Employees at these famed research organizations have mostly kept quiet over the years, fearing retaliation from the organizations or lawsuits for violating nondisclosure agreements. But some are now willing to speak out, and their stories offer a troubling window onto the world of talking apes.

* * *

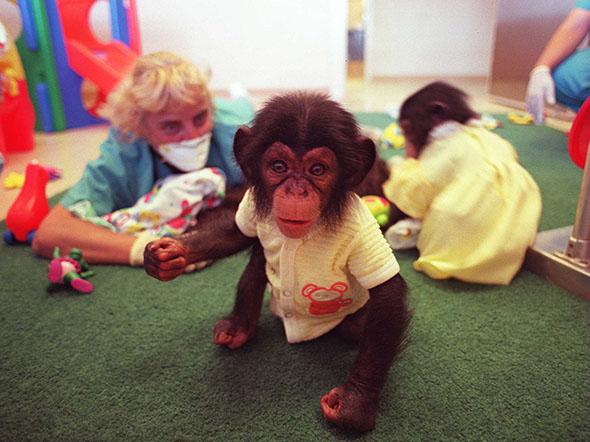

The first attempts to communicate with other primates began in the 1930s. Scientists knew that chimpanzees were our closest relatives and they wondered why chimps didn’t also have language.* Researchers theorized that culture could have something to do with it—perhaps if apes were raised like humans, they would pick up our language. So Indiana University psychologist Winthrop Kellogg adopted a 7½-month-old chimpanzee he named Gua. He raised Gua alongside his own human son, Donald, who was 10 months old when Gua arrived. Time magazine wrote that the experiment seemed like a “curious stunt”; others were critical of separating a baby chimp from her mother or rearing a child with a chimp. At one year of age, Gua could respond to verbal commands, but to her humans’ disappointment, she never learned to speak. The experiment was abandoned after nine months.

Courtesy of Creative Commons

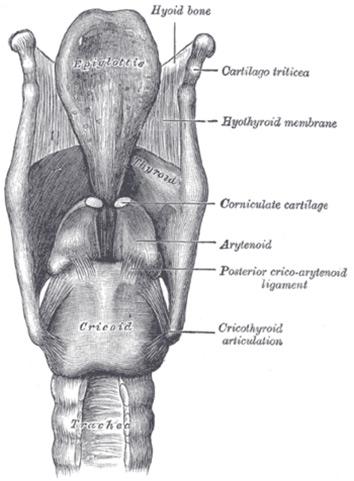

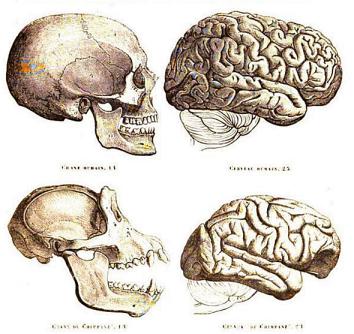

In the following few decades, scientists discovered that anatomical differences prevent other primates from speaking like humans. Humans have more flexibility with our tongues, and our larynx, the organ that vibrates to make the sounds we recognize as language, is lower in our throats. Both of these adaptations allow us to produce the wide variety of sounds that comprise human languages.

In a stroke of genius, researchers decided to try teaching apes an alternate, nonvocal way to communicate: sign language. Washoe, a chimpanzee, was the first research subject. Washoe was born in West Africa, then captured and brought to the United States. University of Nevada psychologists Allen and Beatrix Gardner adopted her in the 1960s. Like Gua, Washoe was raised as a child: She had her own toothbrush, books, and clothes, and the Gardners took her for rides in the family car. Over the course of her life, Washoe learned more than 250 signs, and she reportedly even coined novel words. One famous story has it that she signed “water bird” after seeing a swan. Skeptics remain unconvinced that this was evidence of spontaneous word creation, suggesting that perhaps Washoe merely signed what she saw: water and a bird.

The next decade saw an explosion of human-reared ape language research, and the same cycle of claims and criticism. Scientists named chimps as if they were human children: Sarah, Lucy, Sherman, Austin. Another was named Nim Chimpsky, a playful dig at Noam Chomsky, the linguist known for his theory that language is innate and uniquely human.

Photo by Paul Harris/Getty Images

Scientists tried raising other ape species as well: Chantek, an orangutan; Matata, a bonobo; Koko, a gorilla. Koko, especially, was a sensational hit with the media. Originally loaned as a 1-year-old to Stanford graduate student Francine “Penny” Patterson for her dissertation work, Koko remained with Patterson after the dissertation was complete, and Patterson founded the Gorilla Foundation in 1976 to house Koko and another gorilla, Michael.

* * *

Of the many ape savants studied over the years, two stand out as the most celebrated: Koko the gorilla and Kanzi the bonobo. Both have been profiled repeatedly in the media for their intellect and communication skills.

Koko’s résumé is more impressive than most humans’: She stars in a book called Koko’s Kitten written by Patterson and Gorilla Foundation co-director Ron Cohn, chronicling Koko’s relationship with a tail-less kitten that Koko named All Ball. The book, according to the Gorilla Foundation’s website, is “a classic of children’s literature,” and it was featured on Reading Rainbow in the 1980s. Koko has had her likeness turned into stuffed animals, and she was the guest of honor in two AOL chats, in 1998 and 2000. Koko has also had many celebrity supporters over the years: She’s met Leonardo DiCaprio and the late Mister Rogers. William Shatner says she grabbed at his genitals. Betty White is on her board of directors. Robin Williams tickled her in 2001. At the end of the day that Patterson and other colleagues told Koko about Williams’ death, the Gorilla Foundation announced, Koko sat “with her head bowed and her lip quivering.”

Another media favorite was Kanzi, a bonobo whose brilliance was discovered by accident. Kanzi was born at Yerkes Primate Center in 1980. Kanzi’s mother was a female named Lorel, but a dominant female named Matata laid claim to Kanzi and unofficially adopted him. Matata was being trained to communicate by pointing to symbols on a keyboard called lexigrams that corresponded to English words. Much to the chagrin of her human researchers, Matata showed little interest in her studies, but one day in 1982 Kanzi spontaneously began expressing himself using the lexigram board. From then on, researchers turned their focus to him instead. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, a researcher at Yerkes at the time, had worked with chimps and other bonobos, so she oversaw Kanzi’s training. He quickly built up a lexigram vocabulary of more than 400 symbols. He’s also been said to invent new words by combining symbols, refer to past and present events, and understand others’ points of view, all of which are skills usually attributed only to humans.

Photo by Laurentiu Garofeanu/Barcroft USA/Barcoft Media via Getty Images

These apes are able to communicate with humans, and this alone is a testament to primate cognition. But in the past few decades there has been a spirited debate about whether apes are using language in the same way humans do. One major difference between ape and human communication appears to be their motivation for communicating. Humans spontaneously communicate about the things around them: Adults make small talk with the grocery store clerk about the weather; a toddler points out a dog on the street to her parents; readers write comments about stories on Slate.

Unlike us, however, it seems that apes don’t care to chitchat. Psychologist Susan Goldin-Meadow points out that studies with Kanzi show that only 4 percent of his signs are commentary, meaning the other 96 percent are all functional signs, asking for food or toys. Similar skepticism about Koko emerged in the 1980s, when Herb Terrace, Nim Chimpsky’s former foster parent, published a fairly scathing critique of ape language research, leading to a back-and-forth with Patterson via passive-aggressive letters to the editor of the New York Review of Books. Among other criticisms, Terrace asserted that Koko’s signs were not spontaneous but instead elicited by Patterson asking her questions. Patterson defended her research methods, then signed off from the debate, saying her time would be “much better spent conversing with the gorillas.”

Courtesy of Paul Gervais/Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères/Creative Commons

Critics also allege that the abilities of apes like Koko and Kanzi are overstated by their loving caregivers. Readers with pets may recognize this temptation; we can’t help but attribute intelligence to creatures we know so well. (Or to attribute complex emotions, such as grief over the death of a beloved comic and actor.) I recently wrote an article on a study suggesting that dogs experience jealousy, and the top response from dog owners was: “Anyone with a dog already knows this.” It’s hard to resist reading into animals’ actions, and it turns out, animals read into our actions, too. They carefully watch us for cues about what we want so they can get our attention or treats. In a classic case, a horse named Clever Hans was thought to understand multiplication and how to tell time but was actually just relying on the unconscious facial expressions and movements of his owner to respond correctly.

Long-term studies with human-reared apes are designed to create bonds between apes and their caregivers so that the pair feels comfortable communicating. This closeness often means that the caregiver is the only person able to “translate” for the ape, and it’s difficult to disentangle how much interpretation goes into those translations. As a result, the scientific community is often wary of taking caregivers’ assertions at face value. Some are straight-up skeptics. In a 2010 lecture, Stanford primatologist Robert Sapolsky alleged that Patterson had published “no data,” just “several heartwarming films” without “anything you could actually analyze.”

According to a list of publications on the Gorilla Foundation’s website, this isn’t entirely accurate. They’ve published three papers in the past decade—the latest in 2010—but only one is about gorillas’ cognitive abilities. According to the paper, the data are observational, and come from “unpublished, internal-use video” created by Patterson and another Gorilla Foundation employee, as well as “unpublished lists of Koko’s sign lexicon” and a 1978 paper where Patterson describes Koko’s earliest signs. There is currently no data or video from the Gorilla Foundation available to outside scientists, which makes it difficult for others to evaluate the foundation’s claims. (The Gorilla Foundation says it has been focusing efforts on digitizing its data, and recently announced a project to make it available to researchers.) In lieu of other data to evaluate, a transcript from Koko’s 1998 AOL chat, in which Koko signed something and Patterson translated for the audience, offers an interesting glimpse into how Patterson interprets Koko’s signs. An excerpt:

Question: What are the names of your kittens? (and dogs?)

LiveKOKO: foot

Patterson: Foot isn’t the name of your kitty

Question: Koko, what’s the name of your cat?

LiveKOKO: no

Patterson: She just gave some vocalizations there… some soft puffing

[chat host]: I heard that soft puffing!

Patterson: Now shaking her head no.

Question: Do you like to chat with other people?

Koko: fine nipple

Patterson: Nipple rhymes with people, she doesn’t sign people per se, she was trying to do a ‘sounds like…’

Nipples, as we’ll see, come up a lot with Koko.

In his lecture, Sapolsky alleges that Patterson spontaneously corrects Koko’s signs: “She would ask, ‘Koko, what do you call this thing?’ and [Koko] would come up with a completely wrong sign, and Patterson would say, ‘Oh, stop kidding around!’ And then Patterson would show her the next one, and Koko would get it wrong, and Patterson would say, ‘Oh, you funny gorilla.’ ”

* * *

Criticisms of ape language studies wore down researchers, and projects fizzled out as the humans in charge lost interest in defending their research, being full-time ape parents, and securing ever-more elusive funding to continue the projects. Even as the research ended, though, the apes remained. Depending on apes’ species and gender, the average lifespan for wild apes is between 30 and 50 years, and they often live even longer in captivity. In their post-research lives, these apes, like child stars that peaked early in life, were left to live out their days in less glamorous environments. Apes have been sent around to various private collections and zoos, and, if lucky, ended up in sanctuaries. Ape facilities must obtain licenses from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to showcase the animals (e.g. in a zoo) or to use them as research subjects. But these facilities are largely funded by private donations, and government agencies have little oversight of their day-to-day operations.

Photo by Joe Klamar/AFP/Getty Images

Human-reared apes’ upbringing often made it hard to adjust to the “real world” of captivity, where their companions were other apes instead of doting researchers. It took great lengths to reintroduce Lucy to being a normal chimp. Chantek was separated from his caretaker, Lyn Miles, for 11 years while he lived in a cage at Yerkes, where he grew depressed and overweight. Nim Chimpsky was shipped off to live in a cage with other chimps at a medical center, and he was subjected to research before being sent to an animal sanctuary, where he was reportedly lonely and angry and “killed a poodle in a fit of rage.” And, like child stars, many of these apes die tragic, premature deaths. Gua, abandoned after her study and sent back to a lab, caught pneumonia and died at 3 years old. Nim died of a heart attack at the age of 26; Koko’s companion Michael died of a heart condition at the age of 27.

Of the dozens of ape language projects, just two are still in operation today: the Gorilla Foundation, which houses Koko, now 43, and a male gorilla, Ndume; and the Great Ape Trust, home to Kanzi, 33, and several other bonobos. Both Koko’s and Kanzi’s fame has dwindled over the past decade. When Koko made headlines for her relationship with Robin Williams, the news left many online commenters remarking that it was amazing she’s still alive.

Despite the criticisms of ape research, people jumped at the opportunity to participate in the lives of these famous apes. Beth Dalbey, former communications editor at the Great Ape Trust, said that she was initially charmed by the cleverness of Panbanisha (daughter of Kanzi’s adoptive mother, Matata) and that she wouldn’t have traded the experience for anything else. Former Gorilla Foundation caregiver John Safkow dropped everything when he was hired. “I left a 20-year career because this opportunity came up,” he said. “I thought, ‘This is the coolest job ever.’ ”

But it turned out not to be the coolest job. According to former employees at the Gorilla Foundation—who signed nondisclosure agreements and, in some cases, wish to remain anonymous because they fear retaliation—the apes were poorly cared for, and the employees were subjected to bizarre forms of harassment. (Disclosure: My husband briefly worked at the Gorilla Foundation as a part-time, unpaid volunteer. He was not interviewed or consulted for this article and did not suggest sources for it or introduce me to people who became sources.) When I first emailed Dawn Forsythe, who writes a blog about the ape community called the Chimp Trainer’s Daughter, to request an interview, she warned me that sources might be reluctant to talk to me. “The human world of apes can get pretty nasty,” she said.

Over the course of several months in 2012, nine of roughly a dozen caregivers and researchers at the Gorilla Foundation resigned, and many submitted letters of resignation explaining their decision to leave. Several employees also worked together to submit a letter of concern to the foundation’s board of directors. (The mass resignations and criticism remained internal and have not gotten media attention until now.) “It was a four-page document about our requirements as caregivers, and things we felt were unethical or immoral,” Safkow says. “Incidentally, all of the board members left after we did, too—Betty White is the only one who’s still there.”

I contacted the Gorilla Foundation for an interview, and it requested that I send all questions in email. In response to a question about the letter voicing concerns of departing employees, the Gorilla Foundation emphasized to me that the letter was sent to the board of directors by a researcher, not a caregiver, “who had no first-hand knowledge or experience of anything” in the letter. Regardless of who sent the letter, however, it was composed based on the collective experience of all nine employees who resigned. The Gorilla Foundation told me it hired an animal welfare attorney to review the allegations, who found that they were “totally unsubstantiated.” Additionally, the Gorilla Foundation said these allegations “caused significant internal harm to our organization, which had a negative stress-inducing impact on gorillas Koko and Ndume.”

* * *

At the Gorilla Foundation, many employees’ letters of resignation focused heavily on the issue of the apes’ health. According to former caregivers, Koko was overweight. “All the caregivers would talk about Koko’s weight,” Sarah, a caregiver who resigned a few years ago, told me. (Sarah is a pseudonym; she did not want her real name published because she signed a nondisclosure agreement when she was hired at the Gorilla Foundation.) “We always tried to get her to exercise, but she would never go outside—she just wanted to sit in her little trailer and watch TV or sleep.” The Gorilla Foundation maintains that Koko is not overweight and that at her current weight of 270 pounds she “is, like her mother, a larger frame Gorilla” and within the healthy weight of a captive gorilla. (Wild female gorillas are 150-200 pounds.)

Employees believe that Koko’s weight is the result of an unhealthy diet. In the wild, gorillas are natural foragers who eat mostly leaves, flowers, fruit, roots, and insects. Captive gorillas don’t forage, but zoos typically attempt to make their animals’ diets similar to those of their wild peers.

Sarah was hired in 2011 as a “food preparation specialist” to arrange for Koko’s meals. Given what she knew about gorilla diets from her training as an anthropologist, she was surprised that she was expected to prepare gourmet meals. Soon after she started her job at the Gorilla Foundation, Sarah cooked a Thanksgiving meal for Koko that was also eaten by humans, which concerned her. The Gorilla Foundation says that it does “celebrate the holidays by providing special meals that feature some of the same foods that the caregivers enjoyed.”

“Koko was extremely picky,” Sarah said, and she thinks this was because Koko was often fed delectable human treats, including processed meats. “She would always eat the meat first when she should have been eating plain—not seasoned or salted—vegetables and other greens.” Sarah says that the foods on the diet checklist at the Gorilla Foundation were reasonable and that caregivers tried to stick to those healthy meal plans, even carefully weighing the food to make sure it wasn’t too much. But then, she says, Patterson would visit with Koko and bring in treats. “She would go in with treats like chocolate or meats, and we had no control over it because she would feed it directly to her,” Sarah says. The Gorilla Foundation says that “Koko’s diet includes a wide variety of food and drinks” that “not only cover her nutritional needs, but enriches her life.”

Beyond diet, the quality of gorillas’ veterinary care was a concern. “There were no scientific or veterinary staff to make changes,” says Safkow. “We felt that both Koko and Ndume were not receiving the medical care that was required.” Sarah reports that one veterinarian occasionally visited the site to check on the gorillas but that “it was kind of known he would just sign off on papers, the ones that the Gorilla Foundation needed to be able to have the proper paperwork.” The Gorilla Foundation says it currently has a primary vet as well as backups who visit several times a year.

Safkow, Sarah, and other employees have corroborated that both gorillas were fed massive numbers of vitamins and supplements—Safkow estimated Koko received between 70 and 100 pills a day. (The Gorilla Foundation says she currently takes “between 5 to 15 types of nutritional supplements,” as part of a regimen that “many doctors and naturopaths recommend for preventive maintenance.”) Sarah confirms that as part of her job as a food prep specialist, she was responsible for buying these supplements with the discount she received at a grocery store where she worked part-time. “We had to bribe her with all these things she shouldn’t be eating to get her to take these pills,” said Safkow. The list included smoked turkey, pea soup (“very salty,” Safkow pointed out), nonalcoholic beer, and candies. “We tried chocolate once we had tried everything else,” he said. The Gorilla Foundation denied this, yet it also said that chocolate is good for gorillas’ health—that a cardiologist suggested the gorillas eat 85 percent cacao to ward off heart disease and that the supplements given to the gorillas are “natural” and “high in antioxidants, which are powerful boosters of health and longevity.” Research on antioxidant supplements in humans shows no such thing, however, and they may do more harm than good. In any case, it’s not clear how well research on antioxidants applies to gorillas.

According to multiple former employees, these pills were recommended by Gabie Reiter, a woman who calls herself a “certified naturopath and medical intuitive,” who consulted with Patterson on the phone. Reiter’s website advertises, among other services, chakra alignment and removal of pollutants and toxins through telephone “power tune-ups.” “[Patterson] would be on the phone with [Reiter] almost daily, and Penny would use her for the medical and emotional needs for the gorillas,” Safkow says, adding that Reiter “would make adjustments to her homeopathic medication, all without any scientific or veterinary diagnoses recommending that treatment.” The caption for a 2005 photo on Koko’s website describes her as having the option of taking certain homeopathic cures when she asks for them.

I contacted Reiter to ask about her work at the Gorilla Foundation. At first, she replied to me with a text message, suggesting she was familiar with the organization: “I’m going to talk to Penny Patterson and Ron Cohn first and will get back with you.” A day later, she followed up with an email saying, “After consulting with Penny Patterson, I won’t be available for an interview.” The Gorilla Foundation said that Reiter “uses a combination of kinesthesiological testing and experience” to select “natural” and homeopathic supplements and doses. The foundation maintained that the veterinarian approves all supplements.

Employees also expressed concern about the treatment of Ndume, a male silverback gorilla who was brought to the Gorilla Foundation to impregnate Koko. (Michael, who died in 2000, was originally intended to be her mate, but they developed a sibling relationship rather than a mating one.) For more than two decades, it has been the Gorilla Foundation’s public goal for Koko to have a baby so that she can teach her child sign language. “Koko has been telling us for years that she wants to have a baby,” the Gorilla Foundation wrote to me in an email. Over the years, Koko has been photographed playing with her dolls as “practice for motherhood,” and the Gorilla Foundation says that Koko “chose” Ndume through video dating. He has been on long-term loan from the Cincinnati Zoo since 1991. After 23 years, the two have not mated, and former employees report that they spend all their time separated. Koko and Ndume “can only see each other through two sets of bars,” said Safkow. The Gorilla Foundation said that the gorillas are “strongly emotionally bonded,” “communicate constantly” through a mesh partition, and “care deeply about one another.” The foundation’s website says that while Koko is frustrated about her lack of baby, she is not giving up on “her dream.”

Safkow also said he believed Patterson strongly favored Koko—after all, Koko has been her project for so many years—and would spend time talking and laughing with her in her trailer while Ndume cried. “Patterson does not spend any time with Ndume, except to walk by his window and give him a treat,” he said. “I feel that he’s the real victim.” Sarah agreed, saying, “He’s isolated and forgotten about there.” The Gorilla Foundation denied this.

In 2012, several former employees told the apes’ issues blogger Forsythe that Ndume had not been receiving proper care for years, and Forsythe sent an email to the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services branch of the USDA asking for confirmation that the gorillas were properly cared for. A month later, the USDA reported that certain aspects of Ndume’s care had been neglected, including the fact that he had not been TB tested in more than 20 years. (The USDA recommends gorillas be tested every year.)

Caregivers at the Gorilla Foundation also felt that the leaders of the organization overstepped their bounds in controlling caregivers’ actions. Safkow described a set of closed-circuit cameras from which Patterson could monitor the goings-on of the foundation from her home. “She wanted us to wear phone headsets so she could call us directly,” said Safkow. “So while we’re sitting there with Koko, she’s watching us and calling us and micromanaging all of our interactions. It was insane.” The Gorilla Foundation said that this technology is used to “support gorilla safety, health, research, and care.”

The micromanagement included encouraging employees to do things they didn’t feel comfortable with, all in the name of pleasing the gorillas. In the mid-2000s, the Gorilla Foundation was sued by two former employees for sexual harassment. Nancy Alperin and Kendra Keller alleged that Patterson pressured them to show their nipples to Koko. Patterson apparently thought this was for Koko’s benefit; it was alleged in the lawsuit that Patterson once said, “Koko, you see my nipples all the time. You are probably bored with my nipples. You need to see new nipples. I will turn my back so Kendra can show you her nipples.” The Foundation strongly denied the claims at the time but settled with Alperin and Keller.

Safkow, who worked at the Gorilla Foundation several years after the Alperin and Keller suit was settled, said Koko remained intrigued by nipples. “It was just a given that you show your nipples to Koko,” he said. “Koko gets what Koko wants. We would even hold our nipples hostage from her until she took her pills.” This side of Koko is not presented to outsiders, he says. “It’s different when there’s a big donor. She wants to see their nipples, and points at her nipple and makes a grunting sound—but Penny would spin this to, ‘Nipple sounds like people and what she’s saying is she wants to see more people.’ ” (A similar “sounds like” dialogue appears in the AOL chat transcript from 1998.)

Safkow also recalls an incident when he was pressured to show his nipples to Koko in the presence of several other Gorilla Foundation employees. “At the time, Penny claimed Koko was depressed. We had afternoon ‘porch parties’ where we dressed up for Koko and acted goofy to cheer her up. Koko came up to the mesh between us and asked to see my nipples. It was embarrassing since other people were around, so I told her, ‘Later.’ Then Penny put her hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Do you mean that? I’m just asking because Koko really needs all the support she can get right now.’ ” The Gorilla Foundation said that Koko may make these requests but that it does not ask caregivers to comply. “This seems to be a natural curiosity for a gorilla like Koko, and we don’t censor her communication, we just observe and record it,” the foundation wrote in an email.

* * *

At the Great Ape Trust, which houses Kanzi and several other bonobos, concerned employees took similar action. In September 2012, 12 caregivers and researchers wrote a letter to the board of directors raising concerns about the leadership and judgment of Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, the researcher who led Kanzi’s training. “The Great Ape Trust/Bonobo Hope Sanctuary is not a fit place for 7 bonobos,” they wrote, alleging that they had “observed and internally reported injuries to apes, unsafe working conditions, and unauthorized ape pregnancies.” (The letter was eventually posted on Forsythe’s site and is readable here.)

The Great Ape Trust’s board conducted an investigation in response to employees’ allegations, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which certifies primate facilities. Savage-Rumbaugh was placed on administrative leave from her position as senior scientist and executive director of bonobo research. Despite her official-sounding title, according to her attorneys, Savage-Rumbaugh was not even officially employed by the center at the time she was placed on administrative leave, and had not been since 2008. (In a 2012 interview, Savage-Rumbaugh mentioned that she was asked to accept an “emeritus” researcher designation after asserting that bonobos were making representative art.) According to the Des Moines Register, while the board of directors and USDA completed their investigation, Savage-Rumbaugh’s sister and niece were among the caregivers and volunteers responsible for the bonobos’ care. Savage-Rumbaugh was reinstated days after Panbanisha died of pneumonia in November 2012.

Photo by Laurentiu Garofeanu/Barcroft USA/Barcoft Media via Getty Images

After Savage-Rumbaugh’s return to the Great Ape Trust, criticism of the organization continued. In early 2013, it hosted events that allowed the general public to visit with bonobos directly. Former employees were perturbed that Teco, Kanzi’s baby son, attended public events, because this could have put him at risk for disease. Dalbey, who worked at the organization until 2011, said that would not have been allowed when she was an employee there. “You had to have a reason to be in the building, and the house standards were rigid,” she said. “There’s no telling whether those people had their TB tests and flu shots.” Al Setka, former communications director, agrees. “We were a different organization,” he says. “We didn’t allow public visitations; we were a scientific and educational organization.”

According to Savage-Rumbaugh’s attorneys, she has been barred from access to the bonobos since spring 2013. The Great Ape Trust has recreated itself as the Ape Cognition and Conservation Initiative, and the new science directors of the organization think of it as a new beginning. “This allows us to start from scratch,” says Jared Taglialatela, appointed late last year as the organization’s new director of research. The old organization is “not who we are, and that’s not what we’re hoping to be.”

Recently, however, the organization was under fire when it was announced that Kanzi—who, by some accounts, is overweight—would be judging a dessert-making contest at the Iowa State Fair. Taglialatela said he was “not exactly thrilled with the idea” of having Kanzi participate in the contest but that the board of directors “envisioned that this would be a great way to raise awareness” about bonobo conservation efforts. It was reported that Kanzi would receive desserts directly from the fair, but Taglialatela says the story was wrong: “All of Kanzi’s food is prepared on site with staff.” Regardless of the dietary issues, members of the ape community are still concerned about the exploitation of apes for human entertainment. Taglialatela says the ACCI has tried to make sure the state fair event was as educational as possible. “We’ve tried to make sure that the science and conservation education portion plays center stage in his involvement, and we are confident in seeing that realized,” he says.

* * *

When I asked former employees of the Gorilla Foundation and ACCI (the former Great Ape Trust) what they thought would be the best outcome for the apes still used in language and cognition research, they expressed a combination of desperation and optimism about the future. All the former employees I spoke with emphasized their love for their ape friends and their desire to see them healthy.

From what Taglialatela told me about the ACCI’s new goals, it sounds like the organization is striving to be what Dalbey and Setka said the organization once was: a research, education, and conservation group. Taglialatela says that the ACCI’s “primary mission is scientific discovery” and that he’s hopeful that they’ll be able to win grants and funding to support their research. Previously, he said, it seemed that there was “not much in terms of publication” coming from the organization’s research program, but he said that he hoped to change this. Dalbey and Setka both were hopeful that the new organization would care for the bonobos properly, but they expressed reservations about more invasive research, such as anesthetizing animals for brain scans, which Taglialatela has done in his previous work with chimpanzees. Taglialatela says the research is still in its infancy, so it’s yet to be seen what will happen there.

The ACCI has also been embroiled in a legal dispute with Savage-Rumbaugh and her nonprofit organization Bonobo Hope. A previous legal agreement determined that the Great Ape Trust and Bonobo Hope would share ownership of the bonobos, and a recent court motion declared that ACCI was bound to the same legal responsibilities. It’s unclear, at this point, whether Savage-Rumbaugh will be allowed access to the bonobos again. Taglialatela expressed disappointment that the messy legal process took the focus away from the bonobos, saying that “it is unfortunate that Dr. Savage-Rumbaugh and the [Bonobo Hope] members appear more concerned about her access and her self-interests rather than those of the bonobos.”

Former Gorilla Foundation researchers were in agreement about what they saw as Ndume’s most promising future. Many of the people I spoke with suggested Ndume be put back in the care of the Cincinnati Zoo, which still legally owns him. “Ndume needs to be taken away, back to the Cincinnati Zoo or somewhere he’s able to be socialized into a troop and lead a normal life,” said Sarah. Blogger Forsythe created a petition asking the Cincinnati Zoo to reclaim Ndume, which more than 3,700 people signed. According to Forsythe, the zoo sent several private messages to individuals who posted on the zoo’s Facebook page about Ndume, messages in which the zoo insisted that Ndume is happy and receiving enrichment activities at the Gorilla Foundation. Forsythe sees this fight as a lost cause and has ended the petition. The Cincinnati Zoo has not released any public statements about Ndume and did not respond to requests for comment.

Koko is a more difficult story, and though these former employees are concerned about Patterson’s care for Koko, they recognize that given the close bond between the two, separating them could be disastrous. “Koko needs Penny—there’s no way she could live without Penny,” Safkow says. “Koko’s somewhere in between a gorilla and a human, and there’s really no hope for her outside the Gorilla Foundation.” But Sarah suggests more oversight is needed to ensure the gorillas are healthy. “Koko definitely needs medical care, and she needs a trained vet to get her back on a normal diet,” she said.

Former employees express anger and frustration that the Gorilla Foundation continues to solicit donations for projects that have gone on for decades without success. According to the Gorilla Foundation’s 2013 tax forms, it has collected nearly $8 million in the past five years. Former employees allege that people are misled about what their donations go to. Safkow thinks that the foundation needs to be upfront about the feasibility of its goals. In addition to Koko’s baby, the Gorilla Foundation has been raising money for the gorillas to retire in Maui. The foundation has leased land and hired a surveyor. But from the organization’s tax forms, it appears that no significant progress has been made on the Maui project since 2003. “Just tell people, ‘We need your money to take care of this aging gorilla.’ ” Safkow said. “She’s not having a baby, she’s not going to Maui, but she does need money to help her—she’s one of a kind.”

Others are concerned that the Gorilla Foundation lists ape conservation efforts as one of its primary goals. In 2001, the organization contributed to the construction of a gorilla enclosure in Cameroon named after Michael. According to an ape conservation activist (who wishes to remain anonymous) and three former employees, little has been done since then. The group’s website reports that the Gorilla Foundation sent tens of thousands of copies of Patterson and Cohn’s book Koko’s Kitten to schoolchildren in Cameroon as part of what they call “empathy education.”

Some former employees felt deceived by the way the gorilla research was presented to them when they were hired. Alex (a pseudonym) said he and others were “duped into this fantasy that the foundation is doing amazing work and that we would be a major contributor.” He also thinks that there should be “an apology statement issued to anyone who donated time and money to the foundation.”

When the Gorilla Foundation responded to all these issues, it speculated that the allegations were “seemingly provided … from disgruntled former employees.” One wonders why so many employees were disgruntled in the first place. I sent a message to the only current caregiver I could find contact information for but received no response; remember, employees are made to sign nondisclosure agreements. It may be a coincidence, but a week after I first contacted the Gorilla Foundation for its comments on these allegations, it published a press release on its website announcing several ambitious new projects, including distributing even more copies of Koko’s Kitten in Cameroon, opening up data to scientists, and developing a Koko signing app, and the foundation reiterated its dedication to the “care and protection of Koko and Ndume.” Perhaps the foundation’s operations have changed as a result of the mass resignations in 2012—and many people I spoke with remain hopeful that the organization has taken or will take action to address their complaints.

Koko and Kanzi are still beloved. Their language and cognitive skills are standard parts of intro social science courses. Their names are famous, and you can frequently see references to these apes’ stories in the media. “People just don’t want to hear anything negative,” says Safkow, describing the intrigue surrounding Koko. “You want to believe this fairy tale; it’s magical.”

But like all fairy tales, the one about talking apes is partly make-believe. No matter how much we wish to project ourselves onto them, they are still apes—albeit very intelligent ones. They deserve our respect, and, at the very least, proper care. Our original plan for these apes—to study their capacity for language—has more or less been achieved, and it’s unclear how much more we can learn, as apes like Koko and Kanzi are reaching old age. Through these projects, we’ve learned about the ability of nonhuman apes to associate symbols or signs with objects in the world and to use this knowledge to communicate with humans. We’ve learned about the uniqueness of human language. But we may also have learned something about how strange, stubborn, and fanciful we can be.

*Correction, Aug. 21, 2014: This article originally stated that chimpanzees are our closest ancestors. They are our closest relatives; our last common ancestor with chimps and bonobos lived more than 6 million years ago.