Building a brain sounds like a worthy goal, one that makes it seem as though the future is within reach. Figuring out how our pesky old brains actually work has lots of potential benefits: We could learn more efficiently, cure mental illnesses, or even build smart robots. So last year, the European Union decided, Why not? And the Human Brain Project was born. The EU’s project inspired a similar effort in the United States, called the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative.

In the past few days, more than 500 scientists have said, essentially, Here’s why not. They petitioned the European Commission to make major changes to the HBP, a collaborative initiative to “simulate the brain” in the next 10 years. The project is anticipated to cost more than 1 billion euros, and will be funded jointly by the European Commission and private research institutions.

This is a Herculean task: The brain contains billions of brain cells called neurons, which connect and communicate with one another through trillions of structures called synapses. The HBP’s goal is to map all of these neurons and synapses so that it can build a computer model of the brain. Using that model brain, the logic goes, scientists can learn more about human thought as well as neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Similarly, the United States’ BRAIN Initiative aims to discover “how individual cells and complex neural circuits interact in both time and space.” Government agencies have invested $100 million for the 2014 fiscal year, and it was just announced this week that the Department of Defense is investing $40 million in the project.

In their open message, the scientists raised concerns that the HBP has too narrow a focus to achieve progress in neuroscience research.* The petition was, in part, a reaction to the HBP’s decision last month to shut down the Cognitive Architectures division of the HBP plan, one of the few modules that focused on broader questions such as memory and decision-making, rather than synaptic-level research. Scientists are requesting more transparency in the HBP’s decisions, and they call for the project to “reallocate the funding currently allocated to the HBP core … to broad neuroscience-directed funding.” (The HBP’s board of directors and executive committee issued an official response in which they said they were “saddened” by the petition; the four-page note reiterates the importance of the project but does little to address scientists’ specific concerns.)

The HBP’s leader, neuroscientist Henry Markram, dismisses the naysayers as just averse to change and worried that their labs aren’t going to get funded. Markram’s management style appears to be one reason scientists created the petition; Zachary Mainen, one of the letter’s authors, told Science magazine that the HBP “is not a democracy, it’s Henry’s game, and you can either be convinced by his arguments or else you can leave.”

There are many good reasons to revamp the goals of the HBP, as well as BRAIN. For one thing, the goals of these projects are unfocused. What it means to “understand the human brain” is undefined. HBP and BRAIN have been compared with the Human Genome Project, but that effort was very straightforward. It had a clear goal: sequencing all base pairs of human DNA. And it had clear methods: When the project began, we already had the basic technical tools necessary to sequence genetic base pairs (although improvements in technique sped up the process).

When the BRAIN Initiative was first announced, neuroscientist Eric Kandel pointed out in an interview with the Daily Beast that for the genome project, “We knew the endpoint,” he said. “But here, we don’t know what the goal is. What does it mean to understand the human mind? When will we be satisfied? This is much, much more ambitious.” While Kandel, like many scientists, was excited about the possibilities of the BRAIN Initiative, the undefined goals of BRAIN and HBP mean that they are more susceptible to failure. “I think we’re promising too much,” said UCLA neuroscientist David Hovda. “I don’t think it’s going to be the big breakthrough that people think it will be.”

Another reason BRAIN and HBP are not like the genome project: Your genome does not change from millisecond to millisecond the way a human brain does. What’s more, neurons work in dynamic groups, and we don’t yet have the technology to track those. Tracking single neurons doesn’t tell us much, according to neuroscientists who wrote a 2012 paper that was supposedly the foundational text of the BRAIN Initiative. Doing so would be pointless, write the authors, “just as it would be pointless to view an HDTV program by looking just one or a few pixels on a screen.” Yet this is an explicit goal of BRAIN, which states in grant application information that they’re looking to fund “mechanisms linking single cell or circuit activity to hemodynamic or macro-electromagnetic signals.”

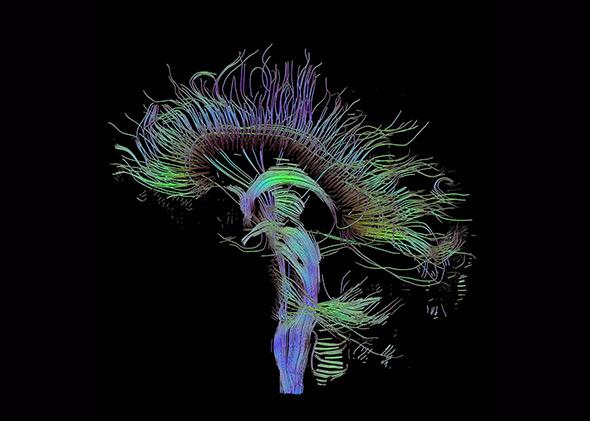

In addition to studying individual neurons, HBP and BRAIN focus on brain imaging and computer simulations of neuronal networks. Research in these fields is important, but they are not the only fields that contribute to our understanding of the human brain. They are sexy, however, and that’s possibly why they’ve been chosen as the narrow focus of the infinitely larger goal of “understanding the brain.” For an example of how models and imaging are the face of neuroscience, look no further than National Institutes of Health’s website describing the BRAIN Initiative, which displays a photo of a colorful brain with a caption that doesn’t describe what the colors mean. On a personal note, I’ve had family members suggest that I use “more gadgets” such as brain imaging to make my developmental psychology research “more scientific.” Models and imaging provide the veneer of precision; they appear to be objective, quantifiable measures of the brain. Pictures of brain activity: You can’t get more scientific than that! We just look at where the brain lights up, and that tells us … what, exactly?

And that’s the problem. Researchers aren’t really sure. Many brain images you see in the news are from functional magnetic resonance imaging studies, which measure blood flow in the brain. The assumption is that there will be more blood flow to parts of the brain that are being used. However, scientists have questioned this simple assumption in recent years. There’s also evidence that certain areas of the brain may serve as blood flow directors, which would further weaken the assumption that blood flow represents brain activity.

Of course, studying what we don’t yet understand can be valuable, and more funding to pin down what brain images mean could lead to huge advances for neuroscience. But assuming that this type of research is the best way forward in achieving our nebulous goal of understanding the brain is disingenuous and misleading. This promotes a certain type of research as important and fuels public perception of those studies as the “real” science. It’s not clear that our pretty brain images tell us more about the human brain than other analyses of human behavior do. This bias also puts institutions that don’t have the funding or infrastructure to support imaging studies at a disadvantage —most fMRIs machines cost between $300,000 and $1 million, and even running a study on a single participant costs around $1,000. Scientists who do not do brain-scanning work contribute valuable insights to research about the human brain, but they are unlikely to receive funding from the HBP or BRAIN for their work.

Like many researchers, I’m thrilled that the brain sciences are finally getting their heyday (and funding). But let’s not limit ourselves to such a narrow scope; after all, people exist in the world, and measuring their behavior in a scanner kind of contradicts the mission of understanding how people’s minds work in their natural states. Leaders at BRAIN and HBP should listen to outside scientists’ requests: If we are to achieve the ultimate goal of understanding the brain, BRAIN and HBP need to widen the scope of the research they fund and define incremental goals. The aim of the Human Genome Project was not to “understand the human body”—it set a definable, achievable goal, and it was a rousing success. We should take the comparison with the genome project more seriously and do the same for HBP and BRAIN.

Correction, July 15, 2014: This article originally stated that in their open message, scientists raised concerns about BRAIN as well as HBP. The petition refers only to HBP. (Return.)