This article originally appeared in NY Mag.

Until earlier this month, most people didn’t know who Slender Man was. But since the news broke that two girls in Wisconsin viciously stabbed a third girl in order to impress the mythological creature, almost killing her in the process, the strange Internet legend has gone mainstream.

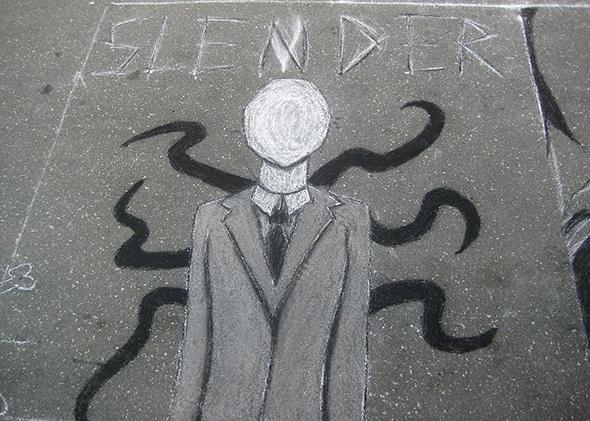

Slender Man, which was originally spawned out of a Photoshop contest on the website Something Awful, is a weirdly popular figure in certain Internet subcultures, the subject of all sorts of fan fiction, artwork, and video games enjoyed by a mostly younger fan base. Science of Us reached out to Trevor Blank, a professor at SUNY Potsdam who studies modern folklore, to ask him to explain why Slender Man holds such appeal for young people online and how he fits into the broader history of youth-oriented folklore and legend.

There are clearly a lot of similarities between Slender Man and other, more traditional folklores and urban legends. How is the online world changing how these stories are told?

We see a lot of the same characteristics that we’ve previously seen in face-to-face communication with telling legends or telling stories about supernatural creatures. There tends to be an emphasis on unverifiability, meaning there’s no way to prove one way or another that it’s true or not true. Because you can’t prove it definitively, it makes it all the more tantalizing to really think about it as being possible. It makes the antagonistic character seem all that more threatening.

The biggest difference online is there’s the ability to create a visual component that you can’t get in oral transmissions. With Slender Man, you can tell a spooky story about a faceless creature that snatches children and shows up in pictures and stuff like that. But when you actually show a picture that is manipulated, that makes it seem like that is real, it takes that unverifiability to a whole other level.

People have definitely gotten weirdly specific with Slender Man. There are cases where people online will even provide the names of little kids who have supposedly been snatched by him.

In one of the very first images of Slender Man that came out of that Something Awful contest, there was an official Chamber of Commerce seal on one part of the picture, making it seem like it came from some small-town government office. Details like these add to the creepiness of it.

But the creepiest thing about Slender Man is you don’t see him until you’re about to be killed or snatched up by him. He can follow you and you might have mental lapses or have madness or memory loss or respiratory problems, but you can only see Slender Man right before death. So, in theory, the only way you can ever find out definitively if Slender Man is real is if you die at his hands.

Not a happy scenario.

Exactly, but that’s also what makes it exciting for a lot of people. There are a lot of people who playfully believe in Slender Man, but deep down they don’t necessarily believe that he’s real. But playing with that line between death and life can be kind of attractive, especially [for] youths who are navigating these boundaries of adolescence. So these kinds of stories serve as symbolic vessels for a lot of anxieties about growing up or the constraints of coming to terms with adult work. But we see things in Slender Man in all types of children’s folklore: There’s the threat of child-snatching and a looming danger in the woods and wariness of strangers. For instance, these elements are in Grimm’s fairy tales, like “Hansel and Gretel.”

So what purpose does a story like Slender Man serve for adolescents and preadolescents, exactly?

The story provides a platform for youths to test ideas and cultivate meaning not just from collecting these stories, but from sharing them with other people, or writing their own versions and sharing them with other people. So they get to experience the story; they hear the motifs, but often create their own iterations, which also helps them to kind of flex their own creative muscles and imagine a darker side of the world — the side of the world that you are running away from as a child but are constantly being pulled into as you enter adulthood, facing these dark realities of the world and leaving innocence behind.

In other words, you’re on the cusp of adulthood, and on some level, you understand that in the adult world, horrible, meaningless things happen all the time. So it’s a way to grapple with that reality that’s usually safe?

Exactly. And I can give you another example that reflects this tension of childhood into adulthood even more—it’s called “Squidward’s Suicide,” featuring the character Squidward from SpongeBob SquarePants. And basically there’s six minutes of excruciatingly detailed footage that the animators put together showing Squidward commit suicide in highly graphic fashion … you know, brains going everywhere. It goes into this really intricate, horrible detail. It’s destroying a childhood character that a lot of youths are familiar with, making it scary, in an effort to kind of underscore the anxiety of transitioning from childhood to adulthood. And it’s never explicitly stated, but this is the functionality that is underneath it all.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

See also: Does Family Medical History Matter?