It rose up out of the sea, a fearsome, roaring monster unlike anything humans had ever seen: horrible, primeval, unstoppable, towering, breathing radioactive fire, and leaving total destruction in its wake.

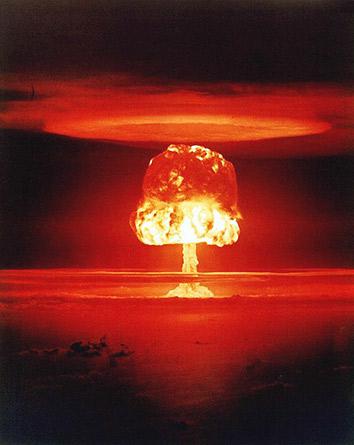

No, this was not Gojira, the lumbering prehistoric beast who hit Japanese movie screens in 1954 and has starred in 30 films since, the most recent of which is just out. This monster was the founding inspiration for Godzilla: the fearsome hydrogen bomb explosion known as Castle Bravo, a test detonated earlier that year in the Pacific that gave birth to far more than cinema’s most famous monster. Castle Bravo played a key role in establishing the deep fear of all things nuclear that persists to this day, helped give rise to modern environmentalism, and even planted the seeds of a basic conflict modern society is struggling with: Are the benefits of modern technology outweighed by the threats they pose to nature itself?

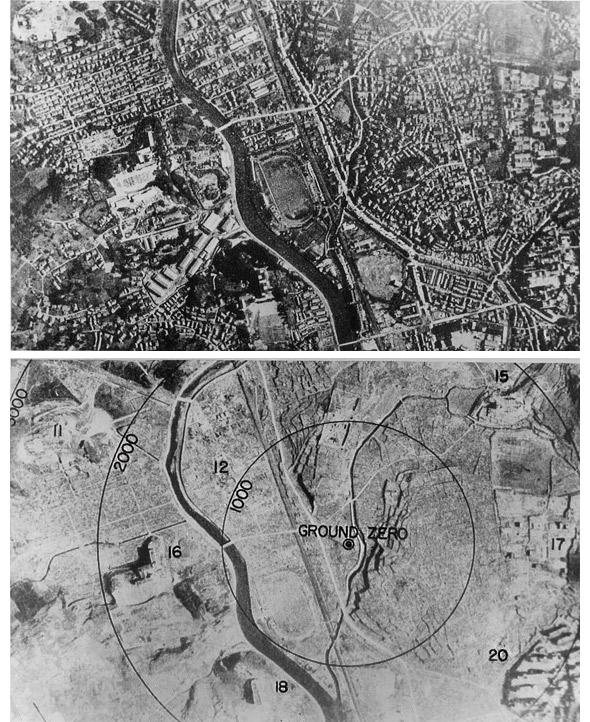

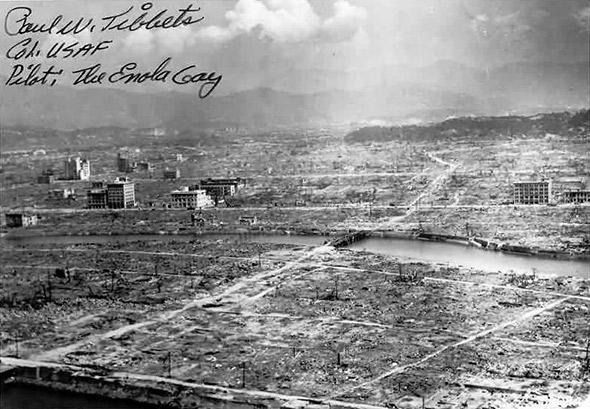

We think now that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki horrified the world, but against the other ghastly horrors of World War II, they didn’t really stand out. The frightening pictures of cities devastated by nuclear weapons didn’t look that much different from Tokyo after the Operation Meetinghouse firebombing of March 9–10, 1945, that killed more people than either atomic weapon.

Not even the outbreak of “A-bomb disease” several years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leukemia cases among the bomb survivors caused by exposure to high doses of radiation, was enough to instill the global fear that was to come.

But the fearsome, roaring, alien monster of Castle Bravo lit the sky like a false sun, creating a fireball so wide it would have vaporized a third of Manhattan and so tall it stretched four times higher than Mount Everest. The scale of the destruction was massively greater than the atomic bombs dropped nine years earlier on Japan … almost too great, too frightening, to comprehend. Now everyone could feel the fear that Manhattan Project director Robert Oppenheimer felt as he watched the first atomic bomb test in New Mexico in 1945, recalling the words of the god Shiva in the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

Courtesy of the National Nuclear Security Administration Nevada Site Office Photo Library/United States Department of Energy

As frightening as the explosion of Castle Bravo was its fallout. When the dust settled, radioactivity had contaminated more than 7,000 square miles, nearly the size of New Jersey. One speck in that vast area of contamination was the Japanese fishing boat Fukuryu Maru, or Lucky Dragon. It was operating in what were supposed to be safe waters, but the explosion was three times more powerful than scientists had expected. The crew of the Fukuryu Maru got back to Japan and, under the glare of international media attention, fell sick from radiation exposure. The Japanese press called it “the second atomic bombing of mankind.”

Now no one on Earth could pretend they were not at risk, either from the vastly more threatening hydrogen weapons themselves, or from radioactive fallout that caused cancer, a disease that the public was just beginning to openly talk about and fear.

What’s more, nature herself was now in jeopardy, threatened with being poisoned, polluted, contaminated by people daring to play God with the very forces of nature. As Spencer Weart reported in his marvelous book The Rise of Nuclear Fear, newspapers called nuclear weapons “a menace to the order of nature” and “a wrongful exploitation of the ‘inner secrets’ of creation.” Pope Pius XII, in Easter messages heard by hundreds of millions around the world, “warned that bomb tests brought ‘pollution’ of the mysterious processes of nature.”

Upon receiving an honor from the Army for creating the atom bomb, Oppenheimer said of the threat of nuclear weapons: “The people of this world must unite or they will perish.” And unite is precisely what people did in the months following Castle Bravo. In 1955, the annual rally against nuclear weapons in Hiroshima was massive, and international news coverage of the rally helped spawn the “Ban the Bomb” movement against both the weapons and atmospheric testing. It was the first truly global protest movement. People were indeed uniting, brought together by fear.

Photo comparison courtesy of the U.S. National Archives

That movement spawned opposition to atomic power, the new form of electrical generation being developed in the 1950s. Some of the most influential leaders of the movement, including Barry Commoner and Rachel Carson, broadened their attention to other ways that technology seemed to threaten human health or nature itself. The modern environmental movement grew directly out of fear of radiation. In fact, Carson was inspired to write Silent Spring, about the threat of the overuse of pesticides, by the similarities she saw between the threat of both forms of fallout: “[T]he parallel between radiation and chemicals is exact and inescapable.”

Opposition to nuclear power and industrial chemicals has been a core theme of modern environmentalism ever since, based on the same inspiration that brought Godzilla up from the depths: We need to protect nature from human-made technology. Those environmental values now also inspire opposition to genetically modified food, or fracking, or large-scale industrial agriculture—any modern technology that allows humans to manipulate and threaten the natural world, the benign true natural world that existed before humans came along and, with their technology, ended it, as Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature suggests.

Of course, humans are a species too, not separate from but a part of the natural world, and like all species our interactions with the natural world have all sorts of impacts. True, the human intelligence that allowed us to master fire has meant that we have done far more harm than other species. But science and technology have also brought fantastic progress and offer great hope, including solutions for the mess technology helped us make in the first place.

Gojira itself raised precisely this conundrum, framing the modern conversation we’re still having. As it ends, Tokyo is in ruins. Humans’ most powerful weapons are useless. The monster has retreated to the depths, but no one is sure if or when it will rise again. The reclusive scientist Dr. Serizawa and our hero, Hideto Ogata, are on a boat heading out to find and destroy him.

Serizawa has finally admitted to Ogata what the film has hinted at: He has a weapon that can kill Godzilla, a technological device, which, dropped into water, sucks all the oxygen out of it. He has kept it a secret until now because “if the oxygen destroyer is used even once, politicians from around the world will see it. Of course, they’ll want to use it as a weapon. Bombs versus bombs, missiles versus missiles, and now a new superweapon to throw upon us all! As a scientist—no, as a human being—I can’t allow that to happen! Am I right?”

Courtesy of Paul Tibbets/U.S. Navy Public Affairs Resources

Ogata replies, “Then what do we do about the horror before us now? Should we just let it happen? If anyone can save us now, Serizawa, you’re the only one!”

Serizawa grabs the device and jumps into the sea, killing Godzilla and sacrificing himself but saving mankind … by using a technological weapon more powerful that the atomic bombs that woke the monster from his prehistoric sleep in the first place.

Geoengineering may be able to help combat climate change. Genetically modified food may help feed a global population soon to approach 10 billion. Safer forms of nuclear energy may power population growth cleanly. Are these technological solutions to some of the damage humans have done to ourselves and the natural world, or are they just versions of Castle Bravo and the Oxygen Destroyer, escalations of a self-destructive technological death spiral? Are those who oppose these technologies just modern Godzillas, rising up like mindless angry monsters willing to cause massive suffering and destruction to defend nature?

These are the questions Castle Bravo and Gojira asked. We are still fighting over the answers.