Excerpted from Edible: An Adventure Into the World of Eating Insects and the Last Great Hope to Save the Planet by Daniella Martin, out now from New Harvest.

A few years ago I gave a talk on insect nutrition to the International Society of Sports Nutrition in Las Vegas. Of all the audiences I’ve ever spoken to, they were the most enthusiastic about edible insects. They all wanted me to alert them the moment an insect protein product of some kind went on the market. Used to a larger degree of skepticism, I remarked on their outpouring of excitement.

“Well,” joked one of the attendees dryly, “if you tell a bodybuilder that eating manure will help him put on muscle, he’ll go out into a pasture with a fork.”

Bodybuilders and extreme athletes tend to be early adopters of nutrition trends. That’s why they are precisely the demographic Dianne Guilfoyle, a school nutrition supervisor in Southern California, hopes to capture with BugMuscle, a protein powder made up entirely of ground insects.

“If people see bodybuilders taking it, they might accept it more willingly,” says Dianne, whose son Daniel is a cage fighter.

There are many benefits to using insects as a base for protein powder. For one, the main existing sources are soybeans and milk whey, both of which cause health concerns for some people.

While insect protein might not be a perfect alternative for those with shellfish allergies, for others it could present an alternative that’s healthier for their bodies and the planet than some of the existing options. Previously, whey protein was the only protein powder source to supply a complete amino acid profile: all nine of the essential amino acids required for human nutrition. But guess what else is a great source of these amino acids? That’s right, insects.

Whey in its natural liquid form is only about 1 percent protein by weight, whereas dried whey is 12 percent protein. Processed whey protein isolate, marketed as the main ingredient in protein powder, is about 80 percent protein by weight. In comparison, dried beef is about 50 percent protein. Dried crickets weigh in at 65 percent protein. That’s in their whole, natural form, without industrial processing, unlike the whey protein isolate. Cricket protein isolate doesn’t exist yet, though it has been proposed.

Courtesy of Edible

Clearly, we’re looking at an interesting possibility here, limited largely by lack of both research and public interest in edible insects.

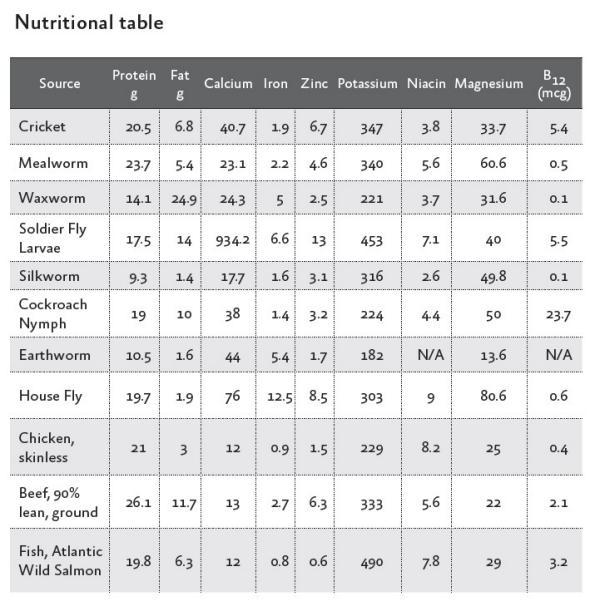

In addition to being high in protein, many edible insect species are also high in essential fatty acids, particularly omega-3s. Aquatic insects tend to have higher levels of essential fatty acids, though all edible insects contain them to some extent. Many insects, such as crickets, grasshoppers, ants, and certain caterpillars, are exceedingly high in calcium. Soldier fly larvae, used for processing compost, are off the charts in this nutrient.

As you may be aware, the nutrient B12 can only be found in animal sources. Crickets and cockroach nymphs are both impressively good sources for B12. If vegans could accept the idea of eating insects, they could potentially manage their B12 intake just by popping a few crickets a couple times a week.

Part of the reason nutrient levels are so high for certain insects is because they are eaten whole, including their exoskeleton and internal organs. Certainly, if more of our livestock were somehow ground up whole and fed to us, we’d get far more nutrition out of them.

Calcium in particular may be high because of the fact that we ingest the insects’ “bones,” or exoskeleton. This protective structure is made out of chitin, a long-chain polymer of acetylglucosamine. It’s the same stuff that shrimp, crab, and lobster shells are made of, as well as the cell walls of fungi (mushrooms). It is structurally similar to cellulose, which makes up the cell walls of plants, and functionally similar to keratin, which our hair and nails are made of. After cellulose, it is the second most abundant natural biopolymer on the planet and is useful in things like biodegradable surgical thread, edible films for preserving fruits and vegetables, as a dietary fiber, and as a potential absorber of cholesterol.

In one episode of The Simpsons, Lisa Simpson faints during a saxophone solo. The doctor chalks it up to an iron deficiency.

“Please say it’s the vegetarianism,” her mother prays. “It’s not the vegetarianism,” snaps Lisa.

“It’s a little bit the vegetarianism,” says the doctor, prescribing iron supplements that clank like railroad spikes into his hand.

Lisa tries taking the monster supplements but complains of vitamin burps all day. Lunch Lady Doris intervenes, giving Lisa a taste of what, she says, keeps her young: beetle mush. Lisa protests that she’s a vegetarian.

“Get real,” scoffs Doris. “There’s bug parts in peanut butter!”

If you peruse the Food and Drug Administration’s accepted food defect levels website, you’ll find that pretty much all processed food has a surprising amount of ground-up bugs in it. Processed food, in this case, is anything that comes in a package: bread, cereal, pasta, condiments, candy, and so on.

Lunch Lady Doris was right: There are bug parts in peanut butter—up to 30 insect fragments per 100 grams, in fact.

For chocolate, it can be anywhere from 60 to 90 fragments per 100 grams. Ground oregano can have 1,250 or more insect fragments per 10 grams.

I like to think of it in terms of a night out at a pizza restaurant. If wheat flour can have 75 fragments per 50 grams, or about a half cup; tomato paste can have 30 fly eggs per 100 grams, or a quarter cup; and hops can average 2,500 aphids per 10 grams, then a meal of pizza and beer could result in, what, 100 fragments per person? Five bits of bug per bite?

If insects are in all of our processed food, that means we’ve been ingesting them our whole lives, since we were babies. Gerber grasshopper and onions, anyone?

David George Gordon, author of The Eat-a-Bug Cookbook, relates a great story about why ketchup bottles wear those paper collars. Before modern homogenization equipment was used to process foods, the darker-colored bug parts would float to the top of the ketchup bottle, leaving an unappetizing black ring. To cover this up, they added a paper ring around the top of the ketchup bottle so people wouldn’t be grossed out when they went to season their fries. Nowadays, the bugs are mixed in a lot better, so they don’t float to the top the way they used to, but for many brands of sauce, the paper collars remain.

Think about it—which tomatoes get cooked and mashed into ketchup? The pretty, shiny, flawless grocery store ones? Or is it more likely the holey, bruised, unsightly ones that might have a bug or two inside? The FDA knows it’s not dangerous to have all these cooked, processed, incidental insects in our food. In fact, it could even be good for us.

Remember that freak-out people had over Starbucks using (a very common) cochineal beetle–derived dye for the red coloring of its strawberry Frappuccino? While people were angrily discussing it over their lattes and espressos, they failed to realize that up to 10 percent of coffee beans themselves can be insect infested, even though this information is readily available on the Internet.

Cochineal coloring, also known as carmine dye or Natural Red 4, was the go-to red dye for foods, drinks, fabrics, and cosmetics until fancy chemicals like Red Dye No. 40 were invented. It is still used commonly today but is steadily being priced out of the market by cheaper synthetics. This may be why products such as Campari, which were originally colored with carmine dye, switched to an artificial dye a few years ago.

We intentionally use many other types of insect products in the foods we eat every day. Honey, for one, which, if you didn’t know already, is actually bee vomit. Silk, of course, comes from the cocoons of silkworms, which is why PETA’s against its use; in order to get silk, millions of baby silk moths have to die. The cocoons are boiled, and the dead pupae are removed and, in some cases, eaten as a snack on the factory floor. Shellac, or confectioners’ glaze, is a resin secreted by the lac bug in the forests of Southeast Asia and is used as a coating for pills and candies like jellybeans. Yes, even Skittles used shellac from lac bugs on its candy until 2009. It’s also used in combination with wax to make our apples look extra appealing.

But served on their own, bugs also present an untapped catalogue of tastes for adventurous epicureans. In general, insects tend to taste a bit nutty, especially when roasted. This comes from the natural fats they contain, combined with the crunchiness of their mineral-rich exoskeletons. Crickets, for instance, taste like nutty shrimp, whereas most larvae I’ve tried have a nutty mushroom flavor. My two favorites, wax moth caterpillars (aka wax worms) and bee larvae, taste like enoki-pine nut and bacon-chanterelle, respectively.

Recently, when I served this grub at the Los Angeles Natural History Museum’s Bug Fair Cook Off, one kid on the judging panel said my Alice in Wonderland dish of sautéed wax worms and oyster mushrooms tasted like macaroni and cheese, while the rest agreed that my Bee-LT sandwich tasted like it was made with real bacon.

Arachnids often taste like a light, earthy version of shellfish, crab, and lobster in particular. This makes sense since, from a biological standpoint, bugs and crustaceans are quite closely related.

These examples are fairly tame and recognizable; most people can swallow the idea of nutty mushrooms and earthy shellfish. But there are also flavors in the bug world that can hardly be equated with anything familiar to most Westerners. The taste of giant water bug practically defies description; as one writer enthused after his first time eating them, “There is simply nothing in the annals of our culture to which I can direct your attention that would hint at the nature of [its] flavor.”

When fresh, these aggressive beetles have a scent like a crisp green apple. Large enough to yield tiny fillets, they taste like anchovies soaked in banana-rose brine, with the consistency of a light, flaky fish. Their extract is a common ingredient in Thai sauces.

Conservative eaters are likely to prefer to stick to what they know, but if you’re anything like me, you’ll find this galaxy of mysterious new flavors simply too compelling to resist.

Excerpted from Edible: An Adventure Into the World of Eating Insects and the Last Great Hope to Save the Planet with permission of Amazon Publishing/New Harvest. ©2014 by Daniella Martin. All rights reserved.