It was a brisk October day in a Greenwich Village café when New York University neuroscientist David Poeppel crushed my dream of writing the definitive book on the science of the self.

I had naively thought I could take a light-hearted romp through genotyping, brain scans, and a few personality tests and explain how a fully conscious unique individual emerges from the genetic primordial ooze. Instead, I found myself scrambling to navigate bumpy empirical ground that was constantly shifting beneath my feet. How could a humble science writer possibly make sense of something so elusively complex when the world’s most brilliant thinkers are still grappling with this marvelous integration that makes us us?

“You can’t. Why should you?” Poeppel asked bluntly when I poured out my woes. “We work for years and years on seemingly simple problems, so why should a very complicated problem yield an intuition? It’s not going to happen that way. You’re not going to find the answer.”

Well, he was right. Darn it. But while I might not have found the Ultimate Answer to the source of the self, it proved to be an exciting journey and I learned some fascinating things along the way.

1. Genes are deterministic but they are not destiny. Except for earwax consistency. My earwax is my destiny. We tend to think of our genome as following a “one gene for one trait” model, but the real story is far more complicated. True, there is one gene that codes for a protein that determines whether you will have wet or dry earwax, but most genes serve many more than one function and do not act alone. Height is a simple trait that is almost entirely hereditary, but there is no single gene helpfully labeled height. Rather, there are several genes interacting with one another that determine how tall we will be. Ditto for eye color. It’s even more complicated for personality traits, health risk factors, and behaviors, where traits are influenced, to varying degrees, by parenting, peer pressure, cultural influences, unique life experiences, and even the hormones churning around us as we develop in the womb.

2. It’s nature and nurture, not one or the other, so I can’t entirely blame my genes for the fact that I love cilantro and loathe broccoli and raw tomatoes. There’s likely a genetic component that determines specific taste receptors. I am sensitive to bitterness, a recessive genetic trait that enables me to detect the presence of compounds called glucosinolates found in most cruciferous vegetables. But chances are, environment played a role, too.

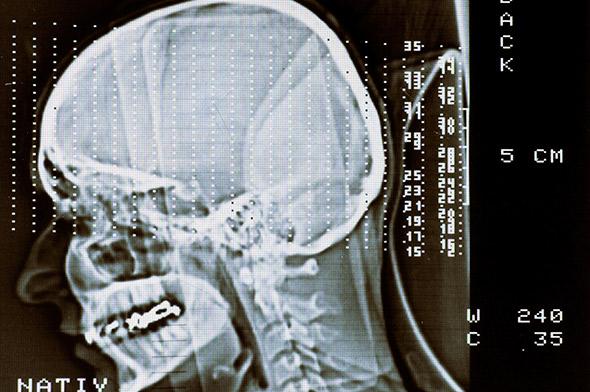

3. My brain scan—courtesy of neuroscientist David Eagleman’s lab—told me nothing about who I am, but it did confirm that I have very clear sinuses. Yes, an entire chapter is devoted to a null fMRI result—or rather, I participated in a group study that has not yet been completed. Science progresses at its own pace and doesn’t care about my book deadlines. Even so, it will reveal very little about me as an individual. The typical image published for an fMRI study is a color-coded visual representation of raw statistical data from many different brain scans, not a snapshot of one person’s brain in action. But I did get to see a very pretty X-ray image of my noggin on a computer monitor and take a fly-through virtual tour of key brain regions (and the sinus cavity).

4. Being shy and being introverted are not the same thing. People are often surprised to learn I was painfully shy as a teenager. I once hid in the girls’ room during a junior-high-school dance, lest I found myself in the terrifying position of having to make casual conversation or dance. I overcame that shyness as an adult, but I am still an introvert. That doesn’t mean I’m antisocial; it just means I need to withdraw from social interactions to recharge my batteries once in awhile. Think of it this way: After a bad breakup, would you rather go out drinking with your friends, or stay home with a pile of DVDs and a pint of ice cream? If the former, you’re an extrovert; if the latter, you’re an introvert.

5. Drunken fruit flies may hold the key to why I’m such a lightweight. Behavioral geneticist Ulrike Heberlein breeds batches of genetically altered fruit flies: Specifically, she knocks out certain genes and tests how this affects their tolerance for alcohol. The strains have names like “Hangover,” “Barfly,” “Tipsy,” and my personal favorite, “Cheap Date.” Those “Cheap Date” flies just can’t hold their liquor. Yet there is no such thing as one alcoholism gene; behaviors cannot be reduced to traits. When it comes to the central question—are alcoholics born or made?—science equivocates by answering truthfully, “Eh, it’s a bit of both, actually.”

6. My avatar alter ego, Jen-Luc Piquant, might be more like me than I realize. Avatars are a virtual extension of the self. We bond psychologically with our avatars and those bonds are stronger the more similarities we share with our pixilated alter egos. We need to be able to look at our avatar and feel “This is me.” But our identities are always in flux. My avatar, which I use for blogging and Twitter, is part of me, but she is not the totality of me, and she may not even be who I am at the moment.

7. I was an incorrigible tomboy growing up, so it’s probably a good thing I wasn’t born in the 17th century, where my dress and behavior would have been deemed “unnatural”—unless I had the good fortune to be born into French aristocracy, where such peccadilloes were tolerated, if not fully embraced. But deeply ingrained attitudes about gender still infuse every aspect of society today, and it remains socially unacceptable, for instance, for little boys to love princesses or Easy-Bake Ovens. That rigid binary thinking needs to change. Such stereotypes arise from lazy thinking, and while they might make it easier to deal with the complexity in the world, they also make it far too easy to lose sight of people as individuals—and they can cause very real psychological harm to those children who don’t fit the stereotypes.

8. I become “that person” at the party if I take LSD. You know the one. Did you see that episode of Mad Men where they all dropped acid and that one woman was crawling around on the carpet? Yeah, that was me. I bonded with an oriental rug on a deep, molecular level, and yet it never calls. Also? It’s really hard to take handwritten notes when you’re tripping on acid because your hand keeps melting into the paper.

9. When I die, and my brain shuts down for good, my self will cease to exist, because consciousness is emergent. It is a real thing—I think, anyway, although some very smart people disagree—but it is still a product of that constant flow of neural information in the brain. “No matter, no mind,” as neuroscientist Christof Koch has phrased it. The world will go on without us after we die—a monstrously heartless thing for it to do. This terrifying thought is at the root of our primal fear of death: We just can’t imagine a world without “I.” We cope by finding our own way to create meaning out of our allotted time on this Earth.

10. We are the stories we tell. We all construct personal narratives, and we spend our lives working and reworking them. Our memories might not be as accurate as we think—we fabricate and embellish even when we believe ourselves to be truthful—but this so-called autobiographical self is key to how we construct a unified whole out of the many components that contribute to our sense of self. You can sequence my DNA, scan my brain, subject me to a battery of personality tests, but you won’t find my essence in any one of them alone. Stories provide that unifying interpretive layer. If you really want to know who I am, let me tell you a story.