In Kurt Vonnegut’s 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle, a central plot element is called ice-nine. The substance, created in a lab, was made up of familiar H2O molecules, but they were locked in a novel crystalline structure that froze solid at room temperature. Because ice-nine crystals could spontaneously convert normal water into more ice-nine, the material was dangerous—just licking it would cause all the water in a person’s body to freeze solid. At the end of the book, a piece of ice-nine is accidentally knocked into the ocean, causing all of the Earth’s water to freeze and ending nearly all life on the planet in an instant.

While Vonnegut was working on his book, a pair of Soviet scientists discovered something eerily similar. But their new form of water—which they made by condensing pure water vapor in ultrathin glass tubes—congealed in tiny, viscous beads, like baby oil, and was 40 percent denser than normal water. Instead of freezing at 0 degrees Celsius, it solidified in a brownish glassy state at minus 40 degrees; no matter how high they heated it, it didn’t boil away. Soon after they announced their find to the world in 1966, American and British scientists scrambled to produce some on their own. The substance, eventually named polywater, seized the imagination of the public (“New Water Doesn’t Freeze,” headlines proclaimed). Engineers speculated about its potential as an anti-freeze or anti-corrosive agent, while some scientists worried about the disastrous possibility that it could escape the lab and seed more polywater on its own.

Until recently, like most people, I’d never heard of polywater. But last year, my father told me he had an uncle, Robert R. Stromberg, who had been a researcher at the National Bureau of Standards in Maryland (now known as the National Institute of Standards and Technology) and was involved in the strange scientific episode. I’d never met the man, but I was fascinated by the scant information I could find about polywater and tickled by the idea I had a family member involved with it. I knew I had to dig deeper.

When I called up my great-uncle and went to visit him at his condo in Leisure World, a sprawling complex for seniors in Silver Spring, Md., I found a sharp 88-year-old with a full head of curly gray hair and a grin that distinctly reminded me of my grandfather, his brother, who died years ago. After lunch in the clubhouse with his wife, Joy, and a tour of their garden plot, we sat next to an outdoor pool to talk. “It’s sort of a long story,” he began, sighing. “But basically, as you know, the material wasn’t what we thought it was.”

For Uncle Bob—and most of the Western world—the story began in 1966, when Boris Deryagin presented his findings at a conference in London. But it really started decades earlier, when a series of obscure papers had hinted that water sometimes behaved weirdly in certain experimental conditions. In the 1920s, the Johns Hopkins chemist Walter A. Patrick, who invented silica gel, noted that occasionally when he used the gel to soak up water and then tried to evaporate it away, some water inexplicably stayed behind. One of his graduate students, a Russian immigrant named Leon Shershefsky, wrote his dissertation on a related phenomenon: When he trapped tiny amounts of water in glass tubes, it too was more resistant to evaporation than it should have been. Years later, on the other side of the world, a Soviet researcher named K.M. Chmutov picked up the thread. He repeated Shershefsky’s experiments, then performed similar ones—confining the water between a flat plate and a curved lens to show that the tube itself wasn’t responsible—and published his findings in 1949.

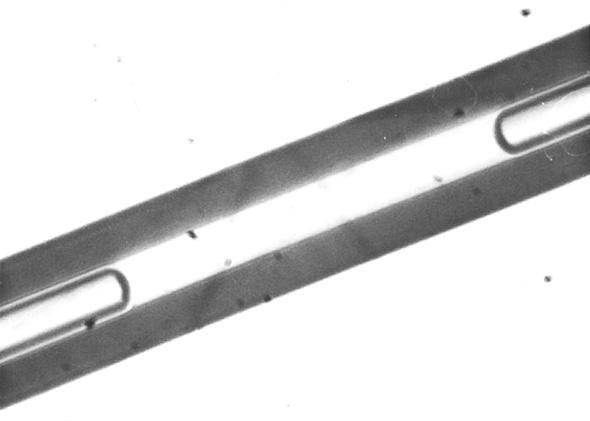

In 1961 another Soviet scientist picked the work up again and isolated for the first time the substance that would eventually be known as polywater. This time, Nicolai Fedyakin, a chemist at the Institute of Light Industry in Kostroma (a scientific hinterland some 400 miles northeast of Moscow), made a key experimental change: Instead of simply trapping water in a tube, he forced it to condense in one, ensuring its purity. As part of his experiments, he piled hair-thin glass capillary tubes horizontally in a sealed chamber with an inch or two of water at the bottom. With a vacuum pump, he lowered the pressure in the chamber, forcing the water to evaporate, and then allowed it to condense inside the tubes. Over the course of a few hours, at either end of the water inside the tubes grew tiny amounts of a mysterious oily substance.

Courtesy of the National Bureau of Standards

Fedyakin called it “offspring water.” Further experiments only deepened the mystery. He calculated that it was 10 times more viscous than normal water and 40 percent denser. In addition to the anomalous freezing and boiling points, it failed to expand when it froze, as normal water does, but instead became even denser. Most importantly, he’d conducted the experiments with sterilized quartz glass tubes and water vapor. The simplest explanation was that he’d created a new form of water out of thin air.

Fedyakin published his discovery in 1962 in a Russian-language journal. Soon after, he was whisked to Moscow by Deryagin, a giant in the USSR’s scientific community, who essentially appropriated Fedyakin’s polywater work for his own research. He told the Western world of the discovery for the first time in 1966 at the Faraday Society in England, then again in 1967 at a research conference in Meriden, N.H.

“At first, a lot of scientists I knew treated it almost as a joke,” Uncle Bob told me, “but I was intrigued by it.” The next year, a British researcher named L.J. Bellamy reported that he’d successfully repeated some of the polywater experiments. My great-uncle quickly decided to grow some of his own.

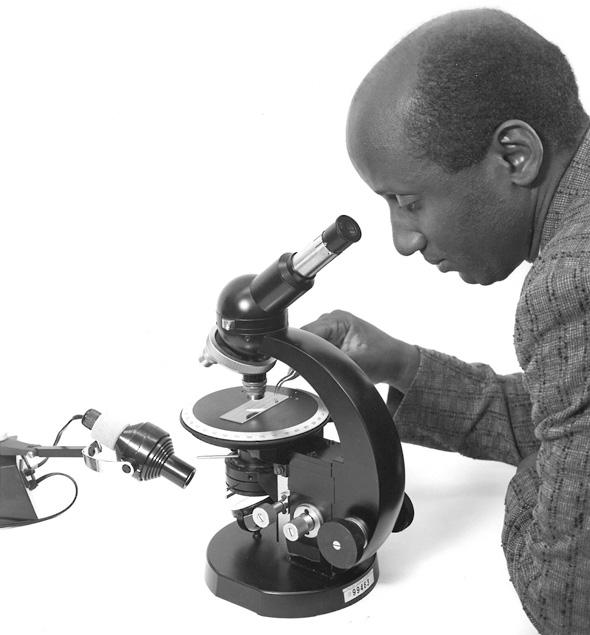

Courtesy of the National Bureau of Standards

Working with his colleague Warren Grant, Uncle Bob found that making a chemical as remarkable as polywater turned out to be remarkably easy. (It was so simple that a few years later Popular Science published “How You Can Grow Your Own Polywater,” a step-by-step guide.) He faithfully followed the Soviet process, using freshly drawn-out, ultrathin Pyrex capillary tubes to avoid contamination. After condensing water in the tubes and leaving them alone for about 18 hours, he’d return to find tiny bubbles of polywater congealing inside. He painstakingly extracted the stuff with a syringe, drop by drop, and over the course of months, was able to amass a gram or two of it, which he used to confirm the substance’s anomalous viscosity, density, freezing point, and melting point.

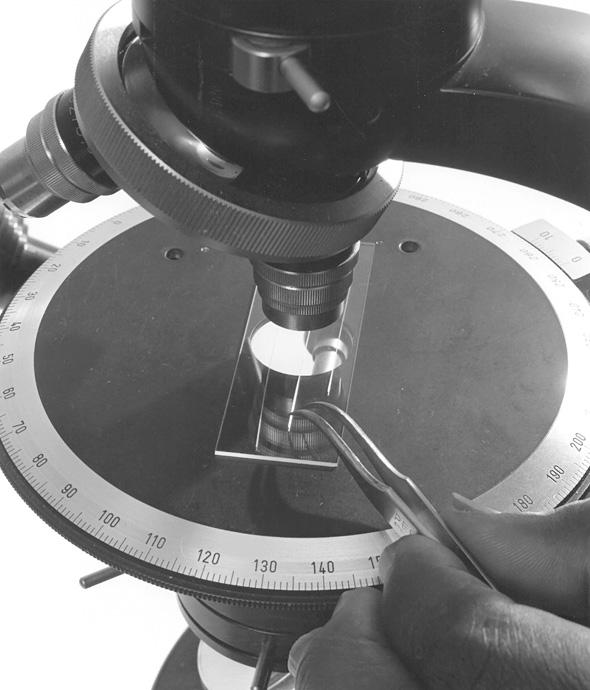

Soon after, in 1969, the Office of Naval Research hosted a special symposium on polywater—a reflection of the military’s strategic desire to avoid ceding a scientific lead in polywater to the Soviets. (Invitations were reportedly restricted to American scientists.) There, my great-uncle saw Ellis Lippincott, a University of Maryland chemist, give a talk on his inconclusive attempts to analyze the infrared spectrum absorbed by polywater. Lippincott had been working with tiny amounts of the substance, produced by the British scientist Bellamy and shipped across the ocean, and desperately wanted to get his hands on more of it. Afterward, my great-uncle approached Lippincott, and the two made an agreement on the spot: They would combine his skill in growing polywater and Lippincott’s expertise and access to equipment (at the time, his lab had one of two microscope spectrometers in existence).

“What we were after was to characterize it,” my great-uncle told me. “What was the structure of it?” To find out, they used spectroscopy techniques, analyzing the light spectrums given off or absorbed by a substance. What they found amazed them. The spectrum of infrared light absorbed by polywater didn’t match any of those in a database of roughly 100,000 substances. They also performed Raman spectroscopy, beaming an argon laser at the sample and measuring the light spectrum it emits afterward. Again, they obtained a unique reading.

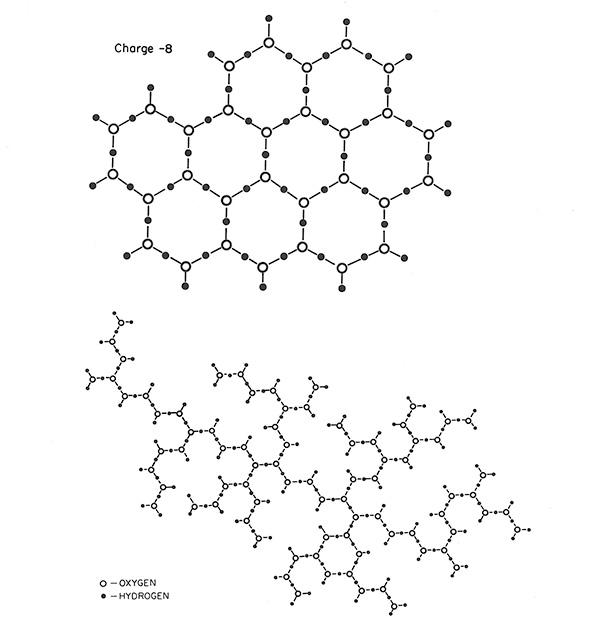

What underlying chemical structure could possibly account for these strange characteristics? They proposed that instead of the Van der Waals forces that normally draw water molecules gently together, polywater was composed of molecules locked in place by stronger chemical bonds, somehow catalyzed by the quartz capillary tubes. The molecules were bonded in linked hexagons, the scientists proposed; in illustrations, they looked like honeycombs made up of water.

Courtesy of the National Bureau of Standards

Just before the team submitted a draft of their analysis for publication, Uncle Bob told me, he coined a catchier term for the chemical everyone had been calling anomalous water. “That just didn’t seem right as a name to me, so I wanted to think of something better,” he said, handing me the original June 27, 1969, issue of Science, which he’d held onto for all these years. “The properties,” his team wrote in the paper, “are no longer anomalous, but rather, those of a newly found substance—polymeric water or polywater.”

The response was beyond anything they could have imagined. The new findings, catchy name, and prestige of the journal Science led the press to take notice of polywater for the first time. Within days, my great-uncle’s team was interviewed by the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Saturday Evening Post, and dozens of other outlets, as I saw from the yellowed clippings he’d kept in a gray folder. Some articles speculated that the work—both his team’s and the Soviets’—might one day lead to a Nobel Prize.

Over the next few months, polywater—and its uncanny resemblance to the world of science fiction—struck a nerve with the public. “It really caught on, because of the fact that it was water,” Uncle Bob told me. “If it had been an unusual structure of something else, nobody would have cared. But everybody uses water—your life depends on it.” Soon, he was fielding calls from industry reps inquiring about polywater’s commercial potential, perhaps as an industrial lubricant or a means of desalinating seawater. The government, fearful that a polywater research gap had developed between the United States and the Soviet Union, took an interest too: the Advanced Research Projects Agency (which later became the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) awarded a grant of $75,000 to Tycho Labs of Boston to mass-produce it. Once, after Deryagin stayed at my great-uncle’s house in Silver Spring while visiting the United States, CIA agents came calling afterward to debrief Uncle Bob about what had occurred.

It’s possible the CIA subscribed to the belief that, like ice-nine in Cat’s Cradle, polywater was capable of uncontrollably self-replicating. That fall, a scientist from Wilkes College named F.J. Donahoe published a letter in Nature in which he argued that the substance could be “the most dangerous material on Earth” and that scientists ought to “treat it as the most deadly virus until its safety is established.” (He was concerned that the polymerization of all the planet’s water could turn the Earth into a Venus, which he believed was desiccated for the same reason.) In response, many scientists—including my great-uncle, disgusted by what he saw as fear-mongering—pointed out Donahue’s logical fallacy: If polywater truly were more thermodynamically stable than water, it already would have proliferated without our intervention, in the small cracks and crevices abundant in nature.

But other scientists felt it did exist in nature, just in minute quantities. Some argued that the substance was responsible for the plasticity of clay. Others said it accounted for the ability of winter wheat seeds to survive in frozen ground and the way some animals are capable of lowering their body temperatures below 0 degrees Celsius without freezing. In total, nearly 100 scientific papers on polywater were published in the year 1970 alone, based on samples generated in labs across the country and fueled by funding from the U.S. Navy.

Still, a note of incredulity hung in the air. When news of polywater first became widely known, some scientists had been doubtful, arguing that impurities were responsible for the phenomenon. Even those who thought they’d produced polywater—including Lippincott and my great-uncle—tried to maintain a posture of skepticism, reporting their findings but leaving open the possibility they were somehow incorrect. “Polywater is so strange that we keep wondering what’s the big goof we’ve been making,” Lippincott told the Washington Post in 1970. “Is there something subtle that’s fooling us?”

* * *

When Denis Rousseau, a postdoc at the University of Southern California, first heard about polywater, he was as intrigued as anyone. “Sergio Porto, this brilliant Brazilian physicist I was working under, came running into the lab one day with the article from Science that your great-uncle had written, all excited,” Rousseau, now the chair of the physiology department at the Einstein College of Medicine, told me when I called him after visiting Uncle Bob. “I started working on it right away.”

He and Porto grew some of their own polywater, and one of the first things they did with it was try to replicate the Raman spectrum data in the paper. But whenever they attempted to get a reading, the laser burned the polywater into a black char. And the Raman spectrum data was a crucial part of my great-uncle’s paper. “That was the thing that led Stromberg to propose the structure,” Rousseau said. “Once I started thinking about it, some things became curious.”

One of those things was a reference that Deryagin made to sodium contamination in his original paper. “Deryagin buried that, and in a journal that, at the time, was only published in Russian,” Rousseau said, “so people outside the Soviet Union didn’t know much about it.” When Rousseau’s team performed an analysis for sodium, they found it in any polywater they were able to produce, along with calcium, potassium, and chlorine.

Courtesy of the National Bureau of Standards

How did these contaminants make it into the supposedly pristine samples? Rousseau had an idea. “I used to play handball regularly, so one time, I squeezed out a sample of sweat from my T-shirt,” he said. Tests showed that the infrared spectrum absorbed by his sweat was virtually identical to the pattern produced by polywater.

He had discovered the disappointing truth: Polywater was just sweaty water. Sodium lactate, a salt derived from human sweat, was entirely responsible for polywater’s otherwise inexplicable qualities. Tiny amounts of perspiration must have dripped or seeped into the chambers then were picked up and carried into the capillaries by the water vapor as it condensed. Deryagin, Lippincott, and my great-uncle hadn’t found a strange, revolutionary form of water; they’d been fooled by the sweat that dripped from their own brows.

Rousseau’s findings, published in the January 1971 issue of Science, were so devastating that polywater’s proponents barely put up a fight. “They said that their material was clean, and ours was dirty, but that got resolved pretty quickly,” Rousseau says. Within months, Lippincott and Stromberg (my great-uncle) published their own analysis, which confirmed that contaminants were to blame; soon afterward, Deryagin’s team followed suit. Just a few years after it was born, polywater was killed. There would be no more research grants and certainly no Nobel Prizes. Polywater had been an artifact of flaws in these scientists’ experiments—and a figment of their imaginations.

* * *

You could charitably argue that the polywater saga wasn’t really a scientific failure, but a success. Scientists continually come up with new theories and disprove them—that’s the scientific method, the way we improve our understanding of the world around us. Most of this messy work stays behind the curtain of unpronounceable names and esoteric formulas. But polywater was uncommonly interesting and got picked up by the press, so its collapse occurred in the glare of the public eye.

But on the other hand, if you look closely enough at polywater, you’ll notice a disconcerting thread that connects it to a handful of other high-profile scientific failures and runs through the present day. In 1989, for instance, two teams of electrochemists independently announced that they’d achieved the holy grail of nuclear energy, cold fusion—that is, controlled nuclear reactions at room temperature. But other scientists were never able to reproduce their results. The amount of nuclear reactions they supposedly detected, it turned out, was within their instruments’ margin of error. Similarly, in 2011, a group of European researchers claimed that they’d observed subatomic particles called neutrinos moving faster than the speed of light, violating our current model of physics. Subsequent analysis showed that their experimental setup included a fiber-optic cable that was incorrectly installed and a clock that ticked at the wrong speed, causing them to time the speed of their neutrinos just a hair too fast.

Rousseau thinks of these episodes as “pathological science”: cases where tiny sample sizes (or effects that are otherwise difficult to measure) and a potentially revolutionary (and career-making) finding lead scientists astray. These aren’t instances of outright fraud, but of unconscious bias. A scientist misinterprets a small amount of data as a paradigm-shifting discovery, and once in that mindset, he or she sees all subsequent information through the same lens.

It’s hard to imagine a better example of this than polywater. “The data was right, but our interpretation was wrong,” my great-uncle told me. Technically, he’s correct: His team produced an accurate infrared spectrum reading of the tiny amounts of the sample they tested, and it didn’t match any other substance in their database. But if they had maintained a more skeptical approach, they might have considered other possibilities—such as sweat—before drawing up a novel chemical structure and giving their material a catchy new name. “The critical thing, whenever you find something that’s really strange, is to try to disprove it, rather than trying to prove it’s there,” Rousseau reminded me. In other words, in their excitement, my great-uncle’s team forgot the maxim popularized by Carl Sagan: Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

To his credit, Uncle Bob isn’t defensive or embarrassed about this mistake—he’s happy to reflect on it all these years later and readily admits that he wishes it had turned out differently. “If it really were true, this would have been Nobel Prize stuff,” he said. At the same time, he harbors no illusions about polywater: “Most mistaken hypotheses in science aren’t entirely wrong, they just have to be modified a bit,” he told me toward the end of our conversation. “I think this was unusual in that we really were 100 percent wrong.”

He’s right: His team’s error was large indeed. But like cold fusion and faster-than-light particles, it wasn’t fraudulent or ill-intentioned—it was simply a reminder that humans guide scientific research, not robots. And humans are subject to desires, which make objectivity really hard to achieve. Ultimately, the discovery of polywater didn’t tell us anything accurate about the chemical nature of water, but it did reveal something fundamentally true about the character of the human mind. If you discovered polywater, you’d want it to be real, too.