At 7:30 this morning Eastern Time, a magnitude-7.7 earthquake struck near the city of Awaran, Pakistan. It will be some time before we know how many people have died, but the outlook is grim. Though the region is prone to large seismic events, Pakistan’s built environment isn’t well-equipped to withstand the effects of shaking.

In the hours and days to come, newspapers around the world will post estimated death tolls from the quake, drawn from the firsthand reports of aid organizations and local government officials. You don’t need to be a seismologist to know that an earthquake in Pakistan, where homes are made of unreinforced brick or rubble masonry, will lead to more collapse and death than one in, say, Italy or California. But how much more, exactly? The headline of an early AP story declares, “Major Quake Kills 2 in Southwestern Pakistan.” Further down, the report cites the district’s deputy commissioner, who tells reporters that “at least two people were killed and five others were injured when more than two dozen houses collapsed.” But we don’t need to wait for newspapers to parcel out the casualties according to their own dramatic timelines. Two groups of scientists have set up careful models of earthquake-related fatalities, in an effort to predict the losses before anyone begins to count the bodies on the ground.

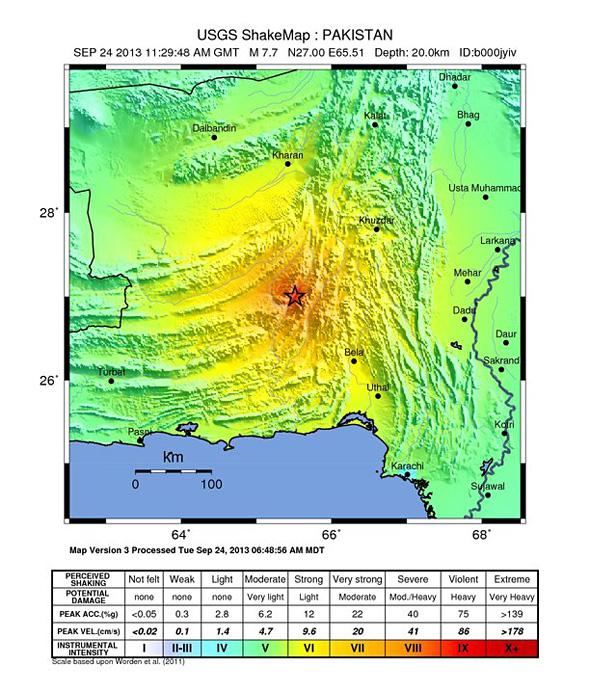

The first, called PAGER (Prompt Assessment of Global Earthquakes for Response) is governed by the U.S. Geological Survey and based in Golden, Colo. The PAGER team takes information from a “shake map”—which guesses how much shaking there will be at various distances and directions from the earthquake’s epicenter—and compares that with a map of local populations. Then they look at data from past earthquakes in the same country or region to figure out the average rate of death for each degree of shaking. By combining the mortality rates, the shake map, and the distribution of people in the area, PAGER comes up with a crude estimate of the final death toll.

This morning’s report from PAGER, which came out 37 minutes after the earthquake hit, suggested that there is a 38 percent chance of more than 10,000 dead and a 73 percent chance of more than 1,000. The most likely single range of casualties, rated at 35 percent, would be between those two numbers (1,000 to 10,000). Given these predictions, the death toll of “at least 2” reported in the newspapers this morning would seem to be a gross understatement.

The second “group” might better be described as a “person”—Max Wyss, a semiretired seismologist based in Switzerland. Wyss runs WAPMERR, the World Agency of Planetary Monitoring and Earthquake Risk Reduction, and he does it by himself (with occasional help from unpaid consultants). Whenever there’s an earthquake, Wyss gets alerts on two phones that are attached to his belt at all times. “I do everything in twos,” he says, “in case one is out of battery or doesn’t work.” Then he pops open one of the two laptops he always carries in his bag and tries to estimate the losses.

The WAPMERR model is more sophisticated than the PAGER version, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s more accurate. Wyss has an enormous dataset of population centers, just like his colleagues in Colorado, but he also has information on the types of buildings in each place. (For bigger cities, he has access to three-dimensional maps of the urban structures.) The types of homes that people live in make all the difference in an earthquake: Bamboo huts, for example, are relatively benign, since they can collapse without killing those inside. Wood-frame, single-story homes are also pretty safe. But shoddily constructed homes of brick or clay can lead to devastation.

Wyss also takes soil conditions into account, since these affect the local shaking, as well as the time of day when an earthquake hits. At night, he says, most people are at home and therefore at greater risk. During the day, they might be in a safer place outside. But these variables might not be as helpful as they seem. “The time-of-day thing flips around depending where you are,” says David Wald, who runs the PAGER team, by way of explanation. In an agricultural economy, people will be safe out in the fields during the working hours. In a more industrial economy, they might be trapped in vulnerable factory buildings.

Today’s report from WAPMERR puts the death toll in Pakistan at between 2,600 and 4,500. That’s several thousand times larger than what’s been reported in the newspapers so far.

Neither Wald nor Wyss ever sees their numbers reported in the press, despite their best efforts to distribute them. “It’s not taken off as much as I would have expected,” Wald told me a few weeks ago. He thinks there’s some laziness about covering disasters. Reporters fall back on reporting the earthquake’s magnitude, as if that tells you everything you need to know about the scope of a tragedy.

The way the news media cover earthquakes misrepresents what’s happening on the ground. The great majority of people killed in an earthquake do not survive beyond the first few seconds, yet rising death-toll figures suggest a deadly event that’s unfolding in real time. In 2009, for example, when a magnitude-6.3 earthquake struck the city of L’Aquila, Italy, the first few hours of coverage suggested that “numerous people” had suffered injuries and that several buildings had collapsed. About six hours after the event, AFP reported “at least 27 fatalities,” and the number climbed steadily from there. Ten hours after the first reports of deaths, the BBC declared a death toll of 92, and the day after that, CNN upped the total to 150. It would be more than four days before the news reports would reach their final count of about 290 dead.

News organizations like to print numbers they can confirm, and reporters may be hesitant to traffic in uncertainties. (What does it really mean to say that PAGER puts the chances of more than 1,000 dead at “73 percent”?) But in other contexts, we’ve seen that official sources often lead the media astray. Just last week, the press misreported several facts about the Washington Navy Yard shooting, and attributed those falsehoods—multiple shooters, someone carrying an assault rifle, etc.—to apparently trustworthy sources in law enforcement. But why should the speculations of a government spokesman be any more newsworthy than the calculations of a team of scientists? Isn’t it more misleading, not less, to let readers think that this morning’s earthquake in Pakistan might only affect a couple of families?

Wyss says this pattern of reporting can be dangerous. He told me about a time he leapt out of bed early one morning to assess an earthquake in Morocco and calculated there would be about 1,000 people dead. Two hours later, BBC and CNN were reporting just two casualties, based on estimates from local officials. “The sun was rising behind the most beautiful Alps that you can imagine, and I knew, with a probability of 95 percent, there were hundreds of people bleeding to death under the rubble of their buildings,” said Wyss. “I was told that I was a silly, old professor, and that BBC knows better.” In the end, more than 600 people were confirmed dead—but Morocco’s government didn’t ask for help until many hours after the earthquake hit.

There ought to be a better way to cover these disasters. We don’t need to pile bodies up in fits and starts, pretending that we never knew how severe the tragedy might be. “The newspapers could have said, ‘two people reported dead … but experts estimate that at the epicenter itself a thousand people may be dead,” Wyss told me, in describing the Morocco quake from 2004.

Let’s do the same today, as the news begins to dribble out from Pakistan. Here’s a better version of the headline in AP:

“Major Quake in Southwestern Pakistan: Two Reported Dead, Experts Guess Several Thousand More”