This week, 64-year-old long-distance swimmer Diana Nyad successfully completed the 110-mile swim from Cuba to Florida. While most of the media coverage focused on her perseverance (this was her fifth attempt), a great deal of it emphasized the supposed danger she faced from sharks. NBC News, ESPN, the Chicago Tribune, and NPR included the phrase “without a shark cage” in the first sentence of their coverage. The AP, the Guardian, Bloomberg News, and Fox News included that phrase in the headline. CNN and CBS News used the phrase “shark-infested waters.” Hillary Clinton tweeted “Feels like I swim with sharks—but you actually did it!” Was Diana Nyad really at risk of being bitten by a shark during her swim? To answer that question, let’s consider a series of related questions.

Are there sharks in the waters between Cuba and Florida? Yes. There are basically sharks wherever there is ocean, including parts of the deep sea and under Arctic ice. Florida is often called the “shark attack capital of the world.” The R.J. Dunlap Marine Conservation Program, where I am a Ph.D. student, has been sampling sharks every week or two in the Florida Keys for more than seven years, and there have been fewer than 10 times when we didn’t catch at least one shark. They’re definitely around. Due largely to overfishing, though, populations of many shark species in the Caribbean have declined precipitously in recent decades.

Photo courtesy Christine Shepard/RJD/Miami University

Are the sharks found between Cuba and Florida particularly dangerous? Most sharks are not dangerous to humans at all. There are more than 500 known species of sharks, and the overwhelming majority have never been known to bite a human. The two largest species of sharks, the whale shark and basking shark, are filter feeders that eat plankton. I have hundreds of photographs of sharks taken while snorkeling or scuba diving, and most of them show sharks swimming away from me as fast as they can, which is their typical reaction to encountering a human.

According to the International Shark Attack File, three species are responsible for the highest number of major injuries and fatalities: the bull shark, the great white shark, and the tiger shark. Other shark species responsible for multiple serious bites include the great hammerhead, oceanic whitetip, shortfin mako, Caribbean reef, spinner, blacktip, lemon, and Galapagos shark. All of these species are found in the waters where Diana Nyad was swimming. An enormous bull shark, approximately 10 feet long and more than 1,000 pounds, was caught by our lab in the Florida Keys last summer. I, for one, would not want to encounter this shark while swimming, but even one this size is extremely unlikely to bite you.

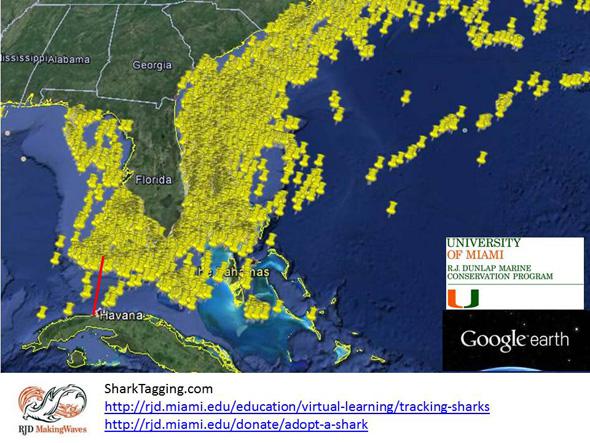

Are there any sharks where Diana Nyad was swimming? Our lab has placed satellite tags on dozens of tiger sharks, bull sharks, and great hammerheads in the Florida Keys, allowing us to track their movements. You can track them yourself using Google Earth from our website. You can also “adopt a shark,” which lets you name it and join us for a day on the research boat. Here are the sharks’ locations compared to Diana Nyad’s route:

Map courtesy RJD/Miami University

Have there been fatal shark bites in the region where Diana Nyad was swimming? There have been 663 shark bites in Florida waters since the 1880s. Only one was in the Florida Keys, and it wasn’t fatal. There have been seven reported fatal attacks in Cuba, but the last one was in the 1930s.

Is anyone who goes in the water in danger of being bitten by a shark? Technically yes, but shark bites are extremely rare. There are approximately 70 to 100 worldwide each year, of which typically fewer than 15 are fatal. The International Shark Attack File has calculated that the average American has a 1 in 3.8 million chance of being killed by a shark. More people are killed by toasters and cows each year than are killed by sharks.

Does long-distance swimming put you at greater risk for being bitten by a shark? There aren’t really enough data points on long-distance swimmers to accurately calculate the relative risk, but consider the following: Typical tips for reducing the risk of being bitten by a shark include staying close to shore, staying in a big group of people, and swimming in daylight hours. Diana Nyad’s long-distance swim, which took more than 50 hours, violated all of these rules. Long-distance swimmers are exposed to unusual situations—a recent swim between Hawaiian Islands resulted in the first-ever bite by a cookiecutter shark.

Does the electric “shark shield” Diana Nyad’s team used repel sharks? No. Not reliably, anyway. I’m also skeptical of wetsuits that supposedly deter shark bites by resembling venomous fish, but at least they look awesome.

Wait, how would you swim with a shark cage? The shark cages used by distance swimmers are very different from the shark cages used for recreational scuba diving with great whites. They are large and dragged behind a boat, and they give what some say is an unfair advantage to swimmers by reducing drag. In 1997, Susie Maroney became the first woman to swim from Cuba to Florida, but she used a shark cage. The frequent use of “without a shark cage” in media coverage could simply be meant to specify which record Diana Nyad technically earned, but we rarely see such attention to technicalities. The phrasing is likely meant to convey the supposed danger of swimming with sharks more than the specific record she earned.

Why do you keep saying “shark bite” and not “shark attack?” The world’s largest association of professional shark scientists issued a resolution this summer asking the AP Stylebook, the Reuters Style Guide, and other journalist organizations to avoid using the term “shark attack.” The phrase is often associated with a large shark and a human fatality, while most interactions between sharks and people are not so serious. Using inflammatory language makes people believe that sharks are more dangerous than they are, when in reality they are ecologically important animals, and many species are experiencing dangerous levels of overfishing. Shark scientists Chris Neff and Bob Hueter recently proposed a scaled labeling scheme to more accurately represent actual risk and outcomes of encounters with sharks.

But Diana Nyad is still awesome, right? Large sharks that have been associated with serious bites are certainly found on Nyad’s route. However, she wasn’t really at much risk of being bitten. Shark populations are rapidly declining in the Caribbean, shark bites are extremely rare, and there hasn’t been a fatal shark bite in the region since before Nyad was born. Regardless of her risk of being bitten by a shark, though, swimming for more than two straight days is still extremely impressive.

Update, Sept. 5, 2013: Did she encounter any sharks? Luke Tipple, a shark expert who was part of Diana Nyad’s safety team, posted a comment that there were encounters with sharks along the route. Specifically, Tipple notes that she was “followed by three oceanic whitetips, two very large hammerheads, and what I suspect to be a large bull shark … it was hard to identify but it was at least 8 feet long.”