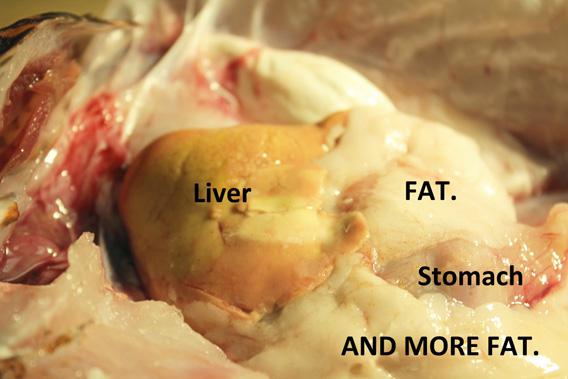

“Do you know what this is?” James Morris looks at me, eyes twinkling, as he points to the guts of a dissected lionfish in his lab at the National Ocean Service’s Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research in Beaufort, N.C. I see some white chunky stuff. As a Ph.D. candidate at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, I should know basic fish biology literally inside and out. When I cut open a fish, I can tell you which gross-smelling gooey thing is the liver, which is the stomach, etc.

He’s testing me, I think to myself. Morris is National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s pre-eminent scientist studying the invasion of lionfish into U.S. coastal waters. He’s the lionfish guy, and we met in person for the first time just a few days earlier. We’re processing lionfish speared by local divers, taking basic measurements, and removing their stomachs for ongoing diet analyses. Not wanting to look bad, I rack my brain for an answer to his question. It’s not gonads. Not spleen. I’m frustrated with myself, but I simply can’t place the junk; I’ve never seen it before. Finally, I give up and admit that I’m completely clueless.

Photo by Christie Wilcox

“It’s interstitial fat.”

“Fat?”

“Fat,” he says firmly. I look again. The white waxy substance hangs in globs from the stomach and intestines. It clings to most of the internal organs. Heck, there’s got to be at least as much fat as anything else in this lionfish’s gut. That’s when I realize why he’s pointing this out.

“Wait … these lionfish are overweight?” I ask, incredulous.

“No, not overweight,” he says. “Obese.” The fish we’re examining is so obese, he notes, that there are even signs of liver damage.

Obese. As if the lionfish problem in North Carolina wasn’t bad enough.

Though comparing invasions is a lot like debating if hurricanes are more devastating than earthquakes, it’s pretty safe to say that lionfish in the Atlantic is the worst marine invasion to date—not just in the United States, but globally. Lionfish also win the gold medal for speed, spreading faster than any other invasive species. While there were scattered sightings from the mid-1980s, the first confirmation that lionfish were becoming established in the Atlantic Ocean occurred off of North Carolina in 2000. Since then, they have spread like locusts, eating their way throughout the Caribbean and along every coastline from North Carolina to Venezuela, including deep into the Gulf of Mexico. When lionfish arrive on a reef, they reduce native fish populations by nearly 70 percent. And it’s no wonder—the invasive populations are eight or more times as dense than those in their native range, with more than 450 lionfish per hectare reported in some places. That is a lot of lionfish.

These alien fish didn’t just come here on their own. Early guesses as to how the lionfish arrived ranged from ships’ ballast water to the coastal damage caused by Hurricane Andrew, but now scientists are fairly sure that no ships or natural disasters are to blame. Instead, it’s our fault. Pretty, frilly fins made the fish a favored pet and lured aquarists and aquarium dealers into a false sense of security. We simply didn’t see how dangerous these charismatic fish were—dangerous not for their venom, but for their beauty. We have trouble killing beautiful things, so instead we choose to release them into the wild, believing somehow that this is a better option when, in actuality, it’s the worst thing we can do. Released animals rarely survive in the harsh real world, but it’s even worse when they do. Pet releases and escapees have become problematic invaders all over the country, from the ravenous pythons in Florida to the feral cats of Hawaii. In the case of lionfish, multiple releases from different owners likely led to enough individuals to start an Atlantic breeding population. Rough genetic estimates suggest that fewer than a dozen female fish began what may go down in history as the worst marine invasion of all time.

Courtesy of Discovery Diving

In North Carolina, the lionfish invasion can be seen at its worst. Offshore, where warm waters from the Gulf Stream sweep up the coast, the lionfish reign. Local densities increased 700 percent between 2004 and 2008. I got to witness the unfathomable number of lionfish firsthand when I dove with the crew of Discovery Diving, a local scuba shop, to compete in North Carolina’s inaugural lionfish derby. I’ve never seen so many lionfish in my life. I didn’t get more than 20 yards from my starting point before I saw hundreds—literally, hundreds. My spear couldn’t fly fast enough to catch them all. On the last day of the tournament, a six-diver team bagged 167 lionfish from one site in two dives, and they didn’t even make a dent in the population on that wreck site. Morris estimates that more than 1,000 lionfish are at this site. Let me tell you, this is what an invasion looks like. An ecological cascade has been set in motion by these Indo-Pacific fish, and scientists are frantically gathering data, learning as much as they can to understand the extent of the damage lionfish will inflict, and figuring out the best responses to protect these fragile marine ecosystems.

Despite the destruction, it’s hard not to be impressed by these colorful aliens. Part of me holds lionfish in the highest regard, with a sort of evolutionary awe. They’re an incredible fish. Given complete creative freedom, I cannot imagine a way to design a marine species more suited to dominance. Sure, they might not be at the top of the food chain like sharks or killer whales, but what they lack in size they make up for in adaptability and reproductive output. The key to their Darwinian success is that they grow fast, mature early, and breed year-round. A single female can release upward of 2 million eggs annually that become larvae capable of floating along currents for more than a month, dispersing for hundreds to thousands of miles. They’ll eat whatever they can get their mouths around, which happens to be any fish or invertebrate just a hair smaller than they are, and they can grow to more than 18 inches long. That means young fish and crustaceans of any species that live where lionfish do are potential targets. And, to top it all off, they are armed with a formidable set of long, sharp venomous spines capable of inducing incapacitating pain. Not surprisingly, nothing seems inclined to eat them. They’re known for their cavalier attitude toward divers, ignoring our presence or possessing the gall to approach us head on, even in the face of a spear. Their cocky resolve is admirable. It’s abundantly clear that these fish fear nothing, not a hungry grouper, not the largest of reef sharks, not even the most effective predators on the planet—us.

Photo by NOAA intern Dave Matthews

Of course, we are perhaps the only animal that lionfish should be fearful of, the only species potentially capable of controlling lionfish populations. Scientists, managers, fishermen, and locals from Venezuela to North Carolina are rallying behind “Eat Lionfish” campaigns. Lionfish tournaments have become annual events in some of the most heavily hit areas of the Caribbean and Atlantic. The Reef Environmental Education Foundation released a lionfish cookbook in 2010 to spur culinary interest and inform fishermen and chefs how to clean and prepare this new delicacy. But even with a serious fishery throughout the invasive range, we will likely never evict lionfish from their new homes. Studies have suggested that we’d need to fish more than a quarter of the mature lionfish every month to stunt population growth, let alone reverse it. Our best hope is to keep local populations low enough to protect key commercial and ecological species, a mission that is proving to be harder and harder as we realize just how much lionfish eat.

We’ve always known that lionfish are formidable predators. As slow-moving fish, they have to be pretty effective hunters to get away with such flamboyant looks. After all, it’s not like their prey won’t see them coming. They practically advertise their presence, waving around their frilly, striped fins with a level of arrogance usually reserved for apex predators. In their native range, young fish run from the sight. But in the Atlantic, native fish have never seen such a bizarre-looking predator. They don’t realize that this colorful display is a warning, not only of their potent venom but also of a nearly insatiable appetite. They don’t flee, and they get eaten. And in North Carolina, the lionfish are eating so well they’ve become fat. No, not fat. Obese.

As James Morris and I measured and sliced 247 fish last month, he explained that we have to monitor their diets to understand how lionfish may impact native fish.

So far, more than 70 different species have been found in the stomachs of invasive lionfish, but detailed data on what they regularly eat in many different areas and throughout the year hasn’t been collected—yet. That’s one of the questions Morris is in the process of answering, and that’s what I helped him with while I was in North Carolina collecting samples for my own research on lionfish venom.

The coast of North Carolina is renowned for its seafood. Cold waters from the north and the warm Gulf Stream converge at Cape Hatteras, creating some of the richest fishing grounds on the Eastern Seaboard. More than 60 million pounds of fish and shellfish are pulled out of its waters every year, worth upward of $1 billion to commercial fishermen. Lionfish are eating a lot of something, and if these gluttons are eating key commercial species, there could be a negative ripple effect on the local economy.

Courtesy of NOAA

One species Morris is particularly concerned about is the vermilion snapper. One of the smallest of the species often labeled as red snapper, vermilion snapper are the most frequently caught snapper along the southeastern United States. Because of their popularity, vermilion snapper populations are closely monitored, and their harvest has been managed in a variety of ways, including limited entry systems, annual quotas, size limits, trip limits, and seasonal closures. So far, government assessments say that the populations are not overfished, but fisheries-watch organizations such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium aren’t convinced. What we know for certain is that vermilion snapper are among the most heavily managed fish in North Carolina, and all of our efforts will be for naught if the lionfish are getting to them first.

So far, it’s not looking good.

I personally pulled vermilion snapper out of lionfish guts last month, along with tomtates and various other reef fish. It’s estimated that lionfish in the Bahamas eat upward of 1,000 pounds of prey per acre per year. Given that lionfish feed largely on small fishes, this equates to hundreds of thousands of individual fish consumed per year by lionfish per acre. But all the interstitial fat I saw suggests that the North Carolinian fish aren’t just eating until they’re full; they’re overindulging on the rich diversity of seafood that North Carolina has to offer. Though lionfish can go weeks between meals, when they don’t have to, they won’t. Scientists have observed lionfish eating at a rate of one to two fish per minute, and their stomachs can expand 30 times their size to accommodate lots of food. To become obese, fish eat upward of 7.5 times their normal dietary intake, which means the abundant North Carolina lionfish could be eating as much as 7,000 pounds of prime North Carolina seafood per acre every year—seafood that we’d much prefer ended up on our plates instead.

In 2010 scientists named the lionfish invasion one of the top 15 threats to global biodiversity. In the three years since, the invasion has only worsened. The only solution is to fight fire with fire, or in this case, pit our bottomless stomachs against theirs. We really do have to eat them to beat them.

Unfortunately, developing a fishery for lionfish isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. They don’t tend to bite hooks and live in complex habitats like reefs and wrecks that can’t be fished with large nets. To catch them, people have to get in the water and spear them one by one—an expensive and tedious way to fish. For lionfish fisheries to turn a profit, demand will have to be high and constant. So far, only a handful of local restaurants have taken the bait, enticing locavores with a truly sustainable menu option. Their business alone isn’t enough, though, to really drive a market.

That’s even assuming that lionfish are completely safe to eat. Recently, the Food and Drug Administration raised flags about lionfish—but not because of their venom. They are concerned that lionfish may contain ciguatoxin, a common tropical poison that causes somewhere between 50,000 and 500,000 cases of ciguatera fish poisoning every year. Ciguatera isn’t unique to lionfish; the disease occurs in tropical waters worldwide. The small lipid ciguatoxins that cause it are made by dinoflagellates, microscopic algaelike animals that live on and near reefs. Animals don’t really break down ciguatoxin, so it bioaccumulates up the food chain, thus large predators that eat high on the food web are most likely to have dangerous levels of ciguatoxin. In areas where the disease is endemic, species such as groupers and barracuda are simply too risky to consume and are often avoided by fishermen. The FDA is concerned that lionfish should also be included on that list, meaning that in areas such as the Virgin Islands, lionfish would be permanently off the menu. Their press release stated that more than a quarter of lionfish sampled contained unsafe ciguatoxin levels, and it issued a warning against eating them.

To other scientists, including myself, the news is baffling. I haven’t seen the actual data (because the FDA has yet to release them), but such high numbers just seem unbelievable. Thousands of lionfish are eaten every year after tournaments, and there hasn’t been a single case of ciguatera from a lionfish. If so many are dangerous, why hasn’t anyone gotten sick? And even if some areas do have ciguatoxic lionfish, surely other areas are safe. After all, we can still eat grouper and other predators from much of the Atlantic and Caribbean. Lionfish shouldn’t be more ciguatoxic than other reef fish—not unless their diet is very, very different.

One of the tough things about ciguatoxin is that we don’t have reliable, direct tests for it. There is a diverse set of indirect assays, all with different methods, different detection levels, and different specificities. All of this makes it hard to compare studies done by different labs and hard to ensure accuracy. Top that off with a species that has never been tested for ciguatoxin before, and things get really messy. This is where my research comes in.

Lionfish possess potent venom that activates sodium channels on the surface of nerve cells, causing a massive influx of calcium. This leads to the release and depletion of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. This happens to be the exact same thing ciguatoxin does. Which, to me, raises a very important question: What if lionfish venom is getting into ciguatoxin assays? Are venom compounds causing false positives? The venom itself, though excruciating in the form of a sting, is harmless on the plate. Unlike ciguatoxin, it’s readily degraded by heat, so if it is venom and not ciguatoxin causing positive tests, lionfish may be safer to eat than the FDA data suggest. Hopefully, the samples I collected on this trip to North Carolina—where ciguatoxin isn’t an issue—will provide some answers.

Courtesy of NOAA

Until we know more, though, promoting fisheries is a potentially dangerous management strategy, at least in certain areas. Some governments have stepped in to promote hunting even without a formal fishery plan, in an attempt to protect their reefs’ future. But many of the small, developing countries in the Caribbean simply don’t have the resources to fund large-scale lionfish removal efforts. For them, steady fisheries would be the only way to get fishermen to catch lionfish instead of currently lucrative species such as grouper.

While we wait to see whether we can drum up the demand, the lionfish are making themselves comfortable. They’re embedding themselves in already fragile ecosystems, restructuring food webs, and pushing reefs toward irreversible ecological cascades. They’re exploring new habitats, discovering the rich resources provided by seagrass meadows and mangroves, even travelling miles inland and upstream in Florida. They’re taking over reefs, wrecks, and rocky territory from the surface to more than 800 feet deep, and they’re gorging themselves on whatever young fish happen to live there. They are, quite literally, growing fat off of our inaction.

That’s not to say there is no hope. Yes, we’re going to have to learn to live with the lionfish. We’re going to have to accept their presence in the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico, but we can use science to arm us against this invasion. In the quiet lab in North Carolina, Morris isn’t just studying fish. He’s preparing us for battle. In this endless war with a formidable foe, knowledge truly is power. The power to predict. The power to pre-empt. The power to fight back and save the species we value most. The power to educate and rally reinforcements to drive back invaders. The more we know about the lionfish, the better our strategies will be to deal with them and future invaders and the better our chances of success. The lionfish caught us by surprise, but Morris isn’t going to let them stay one step ahead. Even if we can’t eradicate these gluttonous fish, we may be able to manage them and minimize the damage they do to our precious marine ecosystems.

Considering it’s our fault that lionfish are here in the first place, it’s really a war against ourselves: against our bad habits, against our casual disregard for the ecosystems that protect and sustain us, against the attitudes and mindsets that led to such a devastating invasion to begin with. It’s a war that, as a nation, as a species, we cannot afford to lose. And one thing is for certain: With so much at stake, it’s going to be a bloody one.