“Baby, you were born this way.” As soon as Lady Gaga sang these words on her smash hit “Born This Way,” they became a rallying cry for gay people around the world, an anthem for sexual minorities facing discrimination. The shiny, catchy song carries an empowering (if simple) message: Don’t be ashamed about being gay, or bi, or trans, or anything—that’s just how you were born. Gaga later named her anti-bullying charity after the same truism, and two filmmakers borrowed it for their documentary exposing homophobia in Africa. A popular “Born This Way” blog encourages users to submit reflections on “their innate LGBTQ selves.” Need a quick, pithy riposte against anti-gay bigotry? Baby, we were born this way.

But were we? That’s the foundational question behind the gay rights movement—and its opponents. If gay people were truly born that way, the old canard of homosexuality as a “lifestyle choice” (or “sexual preference”) is immediately disproven. But if gay people weren’t born that way, if scientists were unable to find any biological basis for sexual orientation, then the Family Research Council crowd could claim vindication in its fight to label homosexuality unnatural, harmful, and against nature.

In recent years, scientists have proposed various speculative biological bases for homosexuality but never settled on an answer. As researchers draw closer to uncovering an explanation, however, a new question has arisen: What if in some cases sexuality is caused by an identifiable chemical process in the womb? What if, in other words, homosexuality can potentially be prevented? That is one implication of one of the most widely accepted hypotheses thus far proposed. And if it’s true, it could turn out to be a blow for the gay rights movement.

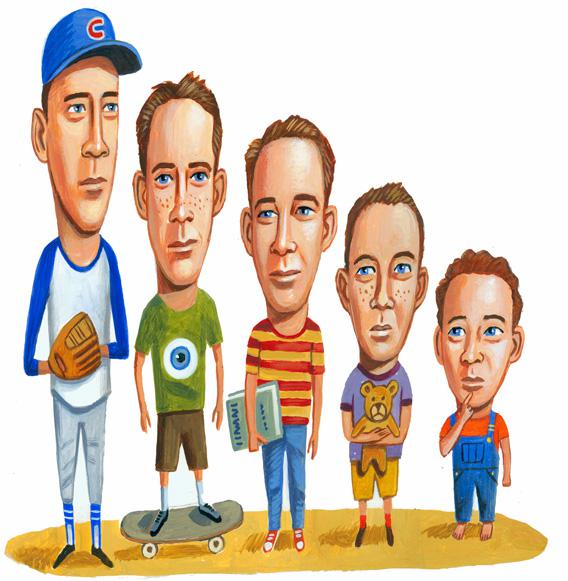

Some of the strongest current evidence that some people are born gay is based on a phenomenon called the fraternal birth order effect. Several peer-reviewed studies have shown that men with older biological brothers are likelier to be gay than men with older sisters or no older siblings. The likelihood of being gay increases by about 33 percent with each additional older brother. From these statistics, researchers calculate that about 15 to 30 percent of gay men have the fraternal birth order effect to thank for their homosexuality.

The fraternal birth order effect is a little perverse. It means that a disproportionate number of gay men are born into disproportionately homophobic households. Couples with large numbers of children tend to be religious and belong to denominations that are conservative and more homophobic. Consider the numbers: 1 percent of Unitarians have four or more children, while 3 percent of evangelical Protestants, 4 percent of Catholics, 6 percent of Muslims, and 9 percent of Mormons have families that large. At the same time, 64 percent of Evangelicals, 30 percent of Catholics, 61 percent of Muslims, and 68 percent of Mormons believe homosexuality should be “discouraged by society.” (Compare that with 15 percent of Jews.) Big families that disapprove of gay people are likely to have gay people in their own clan.

Perhaps these families would be more accepting if the specific biological basis for the birth order effect were elucidated. We know the effect is biological rather than social—it’s entirely absent in men whose older brothers were adopted—but scientists haven’t been able to prove much else. One of the leading explanations is called the maternal immunization hypothesis. According to Ray Blanchard of the University of Toronto, when a woman is pregnant with a male fetus, her body is exposed to a male-specific antigen, some molecule that normally turns the fetus heterosexual. The woman’s immune system produces antibodies to fight this foreign antigen. With enough antibodies, the antigen will be neutralized and no longer capable of making the fetus straight. These antibodies linger in the mother’s body long after pregnancy, and so when a woman has a second son, or a third or fourth, an army of antibodies is lying in wait to zap the chemicals that would normally make him heterosexual.

Or so Blanchard speculates. Although the hypothesis sounds reasonable enough, it’s premised on a number of assumptions that haven’t been proven. For instance, no one has shown that there is a particular antigen that controls sexual orientation, let alone one designed to make men straight. And if that antigen does exist, does it control orientation only? Blanchard refers to its antibody attackers as “anti-male,” implying that the antigen controls for various aspects of masculinity. But when I asked him about this, he was noncommittal. Moreover, the hypothesis proposes a loose, two-way flow of antigens and antibodies between the fetus (whose antigens spread to the mother) and the mother (whose antibodies spread to the fetus). But this exchange has never been observed—and the antibodies and antigens in question are hypothetical, anyway. If they do exist, there’s no assurance that they perform this placental pirouette.

There’s a problem with this explanation. Even though the gay rights movement theoretically wants proof that homosexuality is inborn, this particular hypothesis is, unintentionally, a little insulting. “The scientists behind the [maternal immunization] hypothesis talk about it as if they’re not making judgments, but there are implicit judgments,” says Jack Drescher, former chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Issues. Drescher points out, correctly, that the hypothesis is fundamentally one of pathology. If Blanchard is right, then (at least some) gay people are indeed born gay, but there’s still something wrong with them. The hypothesis turns homosexuality into a birth defect, an aberration: Gay people are deviants from the normative mode of heterosexuality. We may have been born this way, the hypothesis implies, but that’s not how it was supposed to happen.

Drescher is skeptical that scientists will ever uncover a single biological basis for homosexuality—he suspects the root causes are more varied and complex—and suggests that it’s the wrong question to ask in the first place. But the hunt will go on. The gay rights movement, like the black civil rights movement before it, begins with the proposition that we should not discriminate against people because of who they are or how they were born. That’s a belief most Americans share, and it explains the success of the “born this way” anthem. If homosexuality is truly biological, discrimination against gay people is bigotry, plain and simple. But if it’s a birth defect, as Blanchard’s work tacitly suggests, then being gay is something that can—and presumably should—be fixed.

That’s a toxic view, and one that must be abandoned. We might not yet understand the exact biological mechanisms underlying sexual orientation, but we will one day soon. And if, at that point, homosexuality is seen as a disorder, the next step will be a search for a cure. That would be a tragedy—for society and for science. There’s nothing wrong with being gay: You know it; I know it; the Supreme Court knows it. But so long as large swaths of the country believe otherwise—places where homophobic families still ostracize their gay sons and brothers—any research into its biological origins is fraught with peril for the cause of gay rights.