When the Russian asteroid became a fireball in the air over Chelyabinsk, destroying buildings and injuring hundreds, we were lucky it wasn’t worse. What about when the next one hits? Just for fun, let’s say a 10-kilometer-diameter asteroid—much larger than the one over Chelyabinsk but close to the size of one that hit the planet 65 million years ago—smashed into central California. It wouldn’t just destroy Hollywood and Silicon Valley. It would punch a hole in the atmosphere.

That’s what surprises people the most. Every disaster-from-space movie we’ve ever seen prepares us for fire and explosive destruction. Instead, blowback from the strike would be so powerful that it would hurl millions of tons of debris back into space. A thick, toxic cloud layer would settle over our upper atmosphere, wrapping itself around the world within hours after the impact, cutting off the sun. We’re not talking about an ordinary cloud, either. Packed with carbon, dust, and sulfur particles, it would reflect a lot more sunlight than a normal cloud would. Our satellites would record images of a once-blue planet gone brilliant white, like a pool ball. On Earth, it would be twilight for months. Temperatures would plummet. Crops would die, and then the forests.

There would be fires the whole time, of course, especially around the impact site. Plus earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. But most of the 5 billion people who are likely to be killed by an asteroid strike like this would die of famine. In many parts of the world, permanent dusk would mean nothing to feed our animals, let alone our families. Food supplies would dwindle. And that’s when the riots would start.

This is an all-too-plausible scenario for the near future if we suffered an asteroid strike comparable to the one that killed most of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. It wasn’t a giant explosion that exterminated Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, and their kin. In reality, most of those giants died out over thousands of years, their numbers winnowed down to nothing as their food-rich, tropical environments grew barren and cold.

Today, we have solid evidence that confirms environmental changes like these can be blamed directly or indirectly for most mass extinctions that have scourged the Earth. And that’s why our space program isn’t just something educational we’re doing to learn more about the universe. It’s vital to our survival as a species, because the Earth isn’t going to be a safe place for us in the long term.

Courtesy of Doubleday

I learned about the many pathways to mass death while researching my book published this week: Scatter, Adapt and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction. There is a pattern to how mass extinctions happen. A calamity like an asteroid strike or an enormous volcanic eruption causes an initial disaster that kills a lot animals and plants at once. And this leads to climate changes that eventually kill more than 75 percent of all species on the planet, usually in less than a million years—the blink of an eye in geological time.

There is a pattern to survival, too. Every mass extinction has its survivors. A group of furry, mouselike mammals took over the planet after the dinosaurs’ heyday and eventually evolved into us. What these survivors have in common are three abilities encapsulated by the title of my book: They are able to scatter to many places in the world, adapt to them, and remember how to avoid danger. Humans are exceptionally good at all three, but perhaps our greatest strength is an ability to reconstruct the deep history of our planet—and to plan for the future.

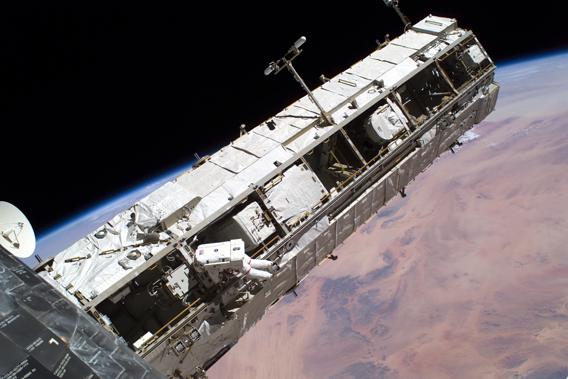

Because we know Earth is inherently dangerous, any long-term plan for humanity has to involve building communities on other worlds, or maybe in vast, artificial environments in space. But the process of doing so will take a lot longer, and be a lot weirder, than what you see in most science fiction stories.

It’s likely we won’t have bustling cities the size of San Francisco on Mars or Titan in the next hundred years, so in the meantime we need to come up with a plan to deal with threats to Earth from space. Already, the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs and space agencies like NASA monitor the skies for potentially deadly asteroids in our neighborhood, called near-Earth objects (NEOs). These groups have already proposed simple solutions to the asteroid problem, all of which are within our technological grasp.

Currently we are using powerful telescopes to map NEOs in the heavens that are bigger than a kilometer—a task that, thanks to NASA, the European Space Agency, and others, is largely complete. If we see an NEO that’s headed our way, we can deploy a small group of spacecraft to nudge it out of the way. As long as we catch an NEO when it is still years away, it is easy enough to push it just enough to change its trajectory so that it misses Earth by tens of thousands of miles. Again, we have the technology to do this today, and a growing space economy to support our efforts.

Next, we need a cost-effective way to leave the planet on a regular basis. Rockets just aren’t going to cut it. Rocket fuel is expensive, heavy, and injects huge amounts of carbon and other toxins into the environment. It’s worked pretty well for our first baby steps into space, just as reed boats worked really well for our ancestors 50,000 years ago when we were first engaging in intercontinental ocean travel. But it’s not a good long-term solution.

That’s why engineers at NASA have long been fascinated by the idea of a space elevator, an enormous structure made of superflexible carbon nanotube fibers. Those fibers would stretch from a dock in the Pacific Ocean, up through the atmosphere, to an asteroid or other counterweight in geostationary orbit roughly 60,000 miles above the Earth. Massive elevators would scramble up the carbon nanotube ribbon, grabbing hold of it with robotic arms, ferrying people and cargo out of our planet’s gravity well without wasting millions of dollars on rockets and fuel. A space elevator could be reused indefinitely, and it would make leaving Earth inexpensive enough that we could actually afford to build habitats in orbit or on other planets.

The one problem with the space elevator is that carbon nanotube ribbon. It’s what you might call an X-material, something that exists in theory but has yet to be proven in the real world. We might wind up building a very different structure, like a massive slingshot or maglev device, to get humans off the planet on a regular basis. The point is that our future space colonization efforts won’t look very much like what our current space programs are building.

Perhaps the biggest lesson here is that the future may be different from what we imagine, but it isn’t an unknown. Sure, things will always happen that we don’t expect. But we have enough data now to predict what the major dangers are—and we need to start planning solutions now. The good news is that we can.

Annalee Newitz will be discussing her new book, Scatter, Adapt and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction, at a Future Tense happy hour in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday, May 15. For more information and to RSVP, visit the Future Tense blog.