An excerpt from the audiobook My Beloved Brontosaurus, by Brian Switek, read by the author. Used by permission of Macmillan Audio.

Triceratops can be an elusive creature. The 30-foot-long, tri-horned herbivore would have been hard to miss on the Cretaceous landscape, but 66 million years later, what’s left only peeks out of the rock in shards and fragments. When I tried to find this great dinosaur in July of 2010, I didn’t have any luck. As I scuffed around a barren outcrop near Elk Ridge, Wyo.—slightly nauseated from the oil drilling fumes I and the rest of the New Jersey State Museum field crew had inhaled as we passed rig after rig on the way out—I kept looking for some glint of ancient enamel or the spongy texture of broken bone. I found the sunbleached, cracked remains of deer, as well as rabbit jaws that were torn out of their skulls by birds of prey, but no skeletons quite as ancient as I was hoping for.

Triceratops is elusive not only in a physical sense. Paleontologists have been struggling to resurrect the dinosaur as a living animal since the early days of the discipline. The bones haven’t changed since the time our ancestors were little fur balls snuffling around a post–mass extinction world, but our conception of what a Triceratops really is has been changing since before the Yale paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh even named the dinosaur. There is constant tension between the dinosaurs we used to know and the ones paleontologists continue to tweak and redefine.

In 1887, Colorado school teacher George Cannon discovered two large horns and part of a skull roof in rock near Denver. He sent these bones to Marsh, who thought the remains belonged to an ancient ungulate—Bison alticornis he dubbed the beast—and Marsh changed his mind only after receiving a mostly complete skull of the creature two years later, showing that the “bison” was really a dinosaur. Marsh named it Triceratops horridus, the first step in an attempt to understand the nature of this fantastic animal that continues to this day. Just before I left for Wyoming, in fact, paleontologists John Scannella and Jack Horner proposed a twist in the natural history of Triceratops that spurred intense debate among paleontologists. When the public heard about the proposal (in a form garbled by confused news reports), the response was a howl of anguish. With Triceratops and other classic dinosaurs, the animals researchers know so intimately conflict, sometimes dramatically, with the cherished monsters of our childhood.

I had plenty of time to think over Scannella and Horner’s hypothesis as I hiked over the exposed remnants of Cretaceous floodplains. The scientists suggested that another horned dinosaur found in the same rocks as Triceratops, named Torosaurus, was not a separate genus of dinosaur after all. Instead, it was actually the fully mature form of Triceratops. Late in life, the paleontologists suggested, the flaring frill at the back of the Triceratops skull changed from a solid structure to a more elongated frill perforated by two large holes. The classic image of Triceratops was of an animal that hadn’t fully grown up. Since no one had apparently found a juvenile Torosaurus, and because it’s unusual to find fully mature dinosaurs, this connection could explain the close resemblance of the two dinosaurs and the rarity of Torosaurus.

Marsh named Triceratops in 1889, and two years later he named Torosaurus. According to the arcane rules of taxonomy, this means Triceratops has precedence and the name would not be eliminated; instead, the name Torosaurus would be sunk. Whether that happens depends on whether or not future studies uphold the idea that the dinosaurs belong to the same genus or scuttle it.

Some journalists came to the mistaken conclusion that paleontologists were about to eliminate Triceratops, one of the most beloved dinosaurs of all time! Dinosaur fans were outraged at the news, voicing their discontent in Internet comment threads and on Facebook. (My favorite protest was a mock-up of a T-shirt featuring three Triceratops howling at Pluto, the recently demoted dwarf planet.) Eventually, word went out that Triceratops was safe, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the public reaction as I searched fruitlessly for more dinosaurs in Wyoming. The Triceratops debacle perfectly highlighted the tension between the pop culture dinosaurs we love and the science that is spurring the evolution of dinosaurian visions.

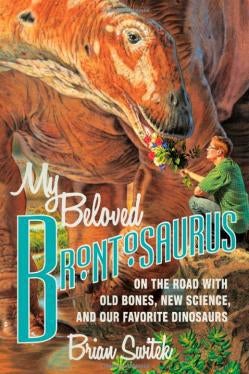

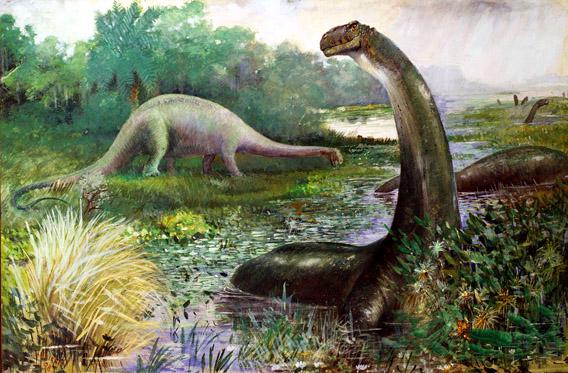

This isn’t the first time paleontology has rocked our relationship with a charismatic dinosaur. Dinosaur expert Elmer Riggs recognized more than a century ago that “Brontosaurus” was not a valid name and that the long-necked, hefty dinosaur should really be called Apatosaurus. For reasons that have never been clear, though, museums and paleontologists continued to use the name Brontosaurus, promoting the image of a dinosaur that never truly existed. No wonder the loss of the great “thunder lizard” still stings. In fact, there’s no better symbol of the constant clash of old and new dinosaurs than that sacred sauropod, which is why the twice-extinct dinosaur became the mascot of my book My Beloved Brontosaurus. From names to the very nature of the animals themselves, new science is pushing the greatest dinosaurian transformation ever seen.

Alterations to our favorite dinosaurs filter into the public consciousness only slowly, often taking a generation or more to become accepted. I’m now an unabashed advocate for fuzzy, fluffy, bristly, and feathered dinosaurs, but before I knew better I couldn’t believe that dinosaurs were different from the scaly monstrosities I grew up with. The fact that Jurassic Park 4 is supposed to feature naked dinosaurs—contrary to the overwhelming evidence science has to offer—confirms that many paleo fans of my generation and older prefer the comfort of recognizable pseudo-dinos to the more realistic ones paleontologists are reviving. But the latest generation of little dinosaur maniacs is fully onboard with the latest science. Then again, today’s dinosaur dreams might become fossilized in their minds, too. I wonder what they will scoff at when they grow up and see future museum displays or films that depict dinosaurs in ways that are strange and unfamiliar from what they learned in their childhoods.

Dinosaur dork that I am, though, I loved every new discovery and change, even if the new discoveries replaced the dinosaurs I grew up with. Paleontologists were digging into details of dinosaur biology—social behavior, reproductive habits, coloration, senses, evolutionary origins, and ultimate extinction—with greater clarity than ever before. Most wonderful of all: One lineage of dinosaur is still with us in feathery, avian form! Dinosaurs are not strange beings dredged from the badlands and left to collect dust in museum displays. Every single skeleton and even bony scrap contains tales of survival, evolution, and extinction, and researchers were pioneering new ways of drawing secrets from those bones. And somehow, no one was talking about this trend, which paleontologist Thomas Holtz Jr. calls the “Dinosaur Enlightenment.” I saw my chance to be an ambassador for the bizarre, enfluffled ranks of new dinosaurs.

Illustration by Charles R. Knight/Wikimedia Commons

Dinosaur books are not an especially varied lot. There are children’s books, popular and technical encyclopedias, and autobiographical accounts of fieldwork by paleontologists. The weight of the literature is as heavy as a hadrosaur skeleton, the advancing wave presenting new images of dinosaurs without accounting for why old images were cast out. Old myths—that Stegosaurus had a brain in its butt, that sauropods were swamp bound, or that dinosaurs went extinct because of some internal inferiority—hung on because no one addressed why those ideas were tossed out. I didn’t want to wait for today’s dinofans to grow up and bring new studies with them, especially since their image of dinosaurs might be updated by then, anyway. As a tribute to my favorite dinosaurs—Allosaurus, Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Parasaurolophus, Apatosaurus, and other classics—I aimed to explain why the slow, tottering, stupid versions of these dinosaurs I grew up with had been ripped apart by dynamic, colorful, and often fuzzy dinosaurs.

The Triceratops and Torosaurus debate gave me a reason to tie together all the new science. Even though my initial inspiration came from this ceratopsid controversy—which is still ongoing, by the way—I eventually picked “Brontosaurus” as my book’s champion. The defunct dinosaur has clung to our imagination with such tenacity that seemingly no one can dispel the sauropod’s ghost. That may not be a bad thing. To understand how far our understanding of dinosaur lives has come, we need a baseline to measure our scientific journey against. What better than a scrapped dinosaur that perfectly encapsulates the outdated notion of idiotic, swamp-bound dinosaurs that nature deservedly wiped out to make way for us? I don’t miss “Brontosaurus”—Apatosaurus is a far more fascinating titan—but I nevertheless cherish the dinosaur because the animal is an icon of the old, slain dinosaurs as well as of how science keeps moving forward by re-examining the old from new perspectives. The book is my tribute to dinosaurs old and new, and writing their stories only fueled my resolve to keep chasing them down.

I’ve been back to the field quite a few times since my 2010 foray into Wyoming’s badlands. All I’ve found of Triceratops is a single tooth from a low hill near Ekalaka, Mont., and I haven’t had the chance to explore the nearby Late Jurassic strata for Apatosaurus. (Though I did purchase a cast of the dinosaur’s skull from the estate sale of the late Utah state paleontologist James Madsen Jr. How could I not?) But I’ve savored every moment I’ve spent shuffling and scrambling over ancient outcrops, wondering about dinosaurs as I try to spot a dinosaur peeking out of the stone.

The best part of the search for dinosaurs is knowing that spotting the clues of a skeleton still resting in rock is just the very beginning of scientific investigation and debate that will continue long after I’m gone—that visions of dinosaurs will continue to change as researchers continue to tap into prehistoric bone. Even though I’ve tried to restore dinosaurs with as much clarity as I’m able to in My Beloved Brontosaurus, I know that the book will ultimately become like Brontosaurus—a time capsule of how we once understood dinosaurs. My scientific spirit overrides my writer’s lament on that point. The transmutation of dinosaurs will continue with every new field find and journal issue, filling out our own evolutionary context with ever-greater clarity. After all, our ancestors scurried under the feet of dinosaurs for more than 150 million years. Dinosaurs undeniably shaped our evolutionary history, just as their extinction allowed mammals a chance to proliferate. The better we can understand dinosaurs and their lives, the better we can envision our own prehistory—their story is our story.