My brother is a weed scientist. Every weekday morning, he drives to work in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle, throws on a lab coat with “Northwest Botanical Analysis” stitched over the pocket, and starts putting tiny samples of ganja through a gas chromatography machine, among other gadgets.* He tells breeders and the “dispensaries” that that currently distribute pot under the local medical marijuana system the potency of their various colorfully named strains as well as the relative amounts of the many subtly different compounds, called cannabinoids and terpenes, that make each one a different experience to smoke. He checks for mites, pesticides, and mold (a common problem with bud grown in Seattle’s damp basements). These days, he’s talking to the state Liquor Control Board as it works on the rules and regulations for retail sales of dope starting later this year.

When I tell people about my brother’s job—that is, when I tell people who are roughly in my demographic of thirtysomething and fortysomething parents—I nearly always get the same response: “Really? Can he score me some weak weed?”

Clearly, there’s a market segment out there that isn’t being catered to by the dope industry. And these relatively affluent customers want something more like a glass of wine at the end of the day than the effect summarized by one recent review of the guava dawg strain in Northwest Leaf magazine: “lung expansion, flavor worthy of a Nobel Peace Prize, and the ability to instantly make my face feel like it’s been shrink-wrapped.”

Marijuana is much stronger than it used to be. Lots of the strains for sale at medical marijuana dispensaries are approaching 25 percent THC, or tetrahydrocannabinol, the compound in the plant known for getting you wicked high. Sitting around a winter solstice bonfire in the Seattle area this December, I heard a woman in her 60s tell a story about her husband taking a tiny toke on a joint that was going around a dinner party, only to pass out in his chair. Another friend and her husband, in their 30s, decided to share a marijuana caramel after their daughter went to bed. They got way too stoned and entered a shared freak-out about how they would deal if she came out to ask for a glass of water.

An elder statesman of Generation X, comedian Louis C.K., has a bit in his Live at the Beacon Theater special about taking “big hits. Like big, 1970s, jean jacket, Bad Company hits” of modern, high potency dope, and then everything going terrifically terrible. “When I was a kid you could just smoke a joint for a while. Now you take two hits and you go insane,” he says. “It’s not doable anymore.”

“Our potencies here are off the scale,” confirms longtime grower Todd Ellison, co-founder of Colorado Marijuana Marketing, a one-stop shop for weed-related entrepreneurs in search of marketing help. “I have a guy who taught me to grow, who has been growing since the ’60s. And this stuff blows him away.” And Ellison agrees. “I am almost 40. I’ve got three kids. You don’t want something that is going to lay you out and make you stupid all day.”

Why is dope so strong? Because plants with big, strong buds maximize the profit of the basement grower. Plus, the people who grow it and sell it also smoke it, and they’ve got high tolerances and a deep fondness for its effects. They like it strong.

When my brother, Andrew Marris, got into the weed-analysis business, he expected that growers would be poring over readouts detailing the concentrations of the various psychoactive components, trying to create perfect, complex masterpieces. Instead, though, he found that many of his customers were obsessively focused on just one statistic: the percentage of THC.

This THC obsession has created a bimodal weed supply. There’s the carefully bred marijuana, with excellent flavor and aroma and pleasing suite of effects—which are ridiculously, hallucinatory, time-stutteringly strong for a casual user. Then there’s ditch weed or Mexican brick weed. Sure, you can smoke it around the campfire until the stars go out, but it smells bad and tastes bad, and nobody is going to bother testing it or perfecting it. What’s missing is lower-potency, high-quality dope.

“Right now, higher potency is a signal of quality product,” says my brother, “because weed grown poorly loses potency.” Good genetics and plants grown by careful, competent growers will result in a “medium-to-high-strength” product, he says. “It has an agreeable smell, vibrant colors.”

I raise my eyebrows about all this color and aroma talk. I chalk it up to stoners who wish they had the same cultural approval as guys who sit around swilling wine all day and talking about oakiness and jam. Dope smells like skunky wet laundry, no? My brother pops into the lab’s back room and comes out with a few samples. Some of them smell like tropical fruit and have strain names to match, like tangerine dragon. A strain called blueberry cheesecake smells exactly like blueberry cheesecake. Super lemon haze actually smells good to me. The complex chemistry explains the bouquet. For example, a terpene called myrcene that they’ve identified in strains like white dawg is also found in mangoes.

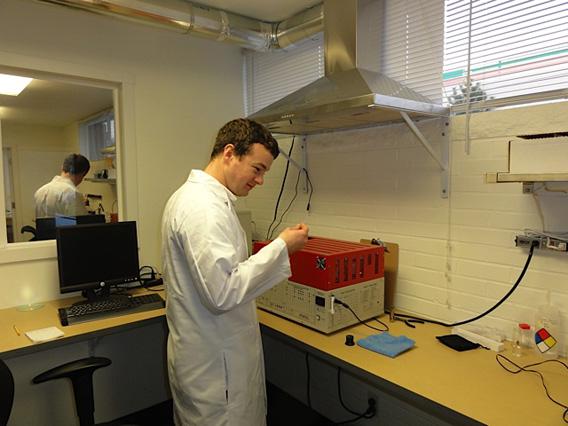

Photo by Emma Marris

These terpenes affect the high as well as the sensory experience of smoking. It is called the “entourage effect.” As the industry matures with legalization and gets beyond its THC obsession, says Muraco Kyashna-tocha, director of the Evergreen State Cannabis Trade Alliance, “We’ll learn we like the 15 percent THC lemon haze with myrcene way more than the 20 percent THC lemon haze with no myrcene.”

Yes, the marijuana industry is about to change, any minute. You can’t exactly walk into a grocery store and buy a sack of weed, but that day may not be that far off. Colorado and Washington state officials are currently hammering out rules and regulations for how the drug can be bought and sold, and by the end of the year, you might be able to pop into a state-run or private shop for a few ounces of the sticky icky on your way home from the office.

Will this new legality expand the market of marijuana customers beyond the current core demographic of guys in their 20s in hoodies and baseball caps with a callous disregard for regular shaving? Yeah. Probably. At least, that’s the read of industry insiders. “Now that the stigma of being a criminal in the eyes of the law (at least here in Seattle) is gone, we foresee a gradual increase in consumption, though perhaps in more benign forms like edibles, drinkables, and topicals. They are much more fun and much less threatening since you don’t have to engage in the act of smoking,” says Lisa Dank, the media coordinator and web consultant for one Seattle dispensary, North Seattle Med. Co.

Back in Colorado, Ellison says that as of now, the demand for straight-up bud comes from men in their 20s, and they pay for potency. “They want to party and get wasted,” he says. But if customers demand something mellower, the industry will supply it. Ellison predicts that large corporations, such as beer companies, might fill the gap, producing large quantities of midgrade weed: not as flashy as the current Cannabis Cup winners, with their crystals of THC glistening under glamorous lighting, but not as pathetic as ditch weed either. “If the big boys come in and come out with a mid-grade” he says, then that new market will be served.

Until then, newbies and those who have been burned by strong weed have a few options. They can make sure that the marijuana they are buying is mostly Cannabis sativa rather than Cannabis indica. Sativa is said to be more cerebral, more placid. Indica, on the other hand, is known for inducing what industry insiders refer to as “couch lock.” If you are in your 40s or 50s, the dope you smoked in high school was probably sativa. “Most of this country, people over 40, the fond memories we have of way back when, when pot made you want to play the guitar and dance in the field, were of sativa,” says Kyashna-tocha. “We were importing from tropical places. But then we started having indoor production. If you grow indoors, you shift to the stuff that is going to maximize production: fast, short, and big impressive-looking buds. That is indica. The shift went to this more stupefying stoned high.”

One caveat about that sativa advice, though. My brother says that there are few, if any, truly pure strains available. Everything has been hybridized many times over in basements and grow rooms from California to Spain.

Another strategy is to go for the bargain parts of the plant. “Oftentimes the dispensary will have the shake and the leaf, which is going to have the same taste, but what you end up with is a less potent pot,” explains Ellison. “That way you maintain the taste and the high but you are not overdoing it.”

My brother says that it takes five months to a year to create a new strain of dope. It might take longer than that for a culture obsessed with potency to realize that there’s a market for something you can smoke after the kids go to bed or on a camping trip of retirees. Marijuana advocates have long countered worries about increased potency with research that smokers adjust and smoke less. But what if people don’t want to smoke less? We don’t all take tiny shots of strong liquor to get our drink on. No, we nurse 5 percent beer so we can keep drinking.

“People don’t want to take one micro-puff of a tiny little doobie and say, ‘We’re done,’ ” my brother says. “They want to share in the social aspect.” He moves his hand in a circle to indicate the archetypal joint-passing ring.

Weed breeders, take note. You can take your time on that 10 percent THC strain with the complex symphony of canabinoids and terpenes, calm muscle relaxation, creative headspace, and beautiful tropical aroma. But those rich baby boomers and Gen-Xers aren’t getting any younger.

Correction, March 21, 2013: This article originally misspelled the name of the Fremont neighborhood in Seattle.