Can You Guess These Athletes’ Nationalities?

Olympians may reveal their origins with just a smile.

Photo by Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

Watching the Summer Olympics can be confusing; there are people of more nationalities in one place than you’d see in a Coke commercial. Depending on the sport, it can be hard to tell where the athletes are from (there’s not a lot of flag space on a Speedo). One minute you’re cheering for what you think is an American hero, the next she’s waving a Union Jack over her head and belting out “God Save the Queen.” But several decades of research suggests there are subtle ways to pick an American athlete out of a crowd based on just a smile or a wave.

In the 1960s and ’70s, psychologists Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen showed that people all over the world use the same facial expressions to convey basic emotions. They studied the Fore, an isolated, preliterate culture from the highlands of New Guinea. Through a translator, Ekman and Friesen told stories to a group of Fore describing different emotions, such as happiness, sadness, fear, and disgust. Then they showed the New Guineans pictures of facial expressions and asked them to match the picture to the story. Despite their seclusion, the Fore understood facial expressions in the same manner as a control group of New Guineans who spoke English, watched movies, and went to school. Happiness, for instance, was nearly always associated with mouth turned up at the corners.

Other studies have shown that emotional facial expressions are inborn. The congenitally blind, for instance, smile just like everyone else, despite the fact that they’ve never seen a happy face to mimic. You can crack a smile in Bolivia or Bahrain, and the locals will know that you’re happy. But nature doesn’t totally trump nurture. Recent studies suggest that facial expressions have accents, like an Australian bartender offering you a “bear.” And these cultural quirks of nonverbal expression can reveal the difference between us and them.

The first experiment to demonstrate a widespread ability to spot nationality was conducted by Georgetown University psychologist Abigail Marsh. While working at Harvard with colleagues in 2003, Marsh showed pictures of emotionally expressive faces made by Japanese-Americans and Japanese nationals to a sample of 79 adults raised in the United States and Canada. The pictures depicted angry, disgusted, sad, surprised, and fearful facial expressions. At well above chance, participants were able to guess which photos showed Japanese-Americans. There are, it seems, subtle differences between an American frown and a Japanese frown. (Presumably, Japanese nationals can also spot this difference.)

Marsh and her colleagues ran a similar experiment in 2007, but this time they used pictures of Australians’ and Americans’ facial expressions. Once again, Americans were able to guess the nationality of the person pictured based on a facial expression, in this case a smile. The ability disappeared when people were shown neutral expressions. Other behaviors also contain nonverbal accents that give away one’s nationality. Marsh showed her test subjects black-and-white photos of Americans and Australians either waving hello or walking. The actors in the images wore surgical scrubs and hairnets to eliminate regional clues like cowboy boots and cork hats. People could gauge whether they were looking at an Australian or an American with a still shot of a wave or a stride.

Nonverbal accents might reflect differences in personality between cultures. Australians, Marsh told me, tend to rate themselves as more agreeable and extraverted than Americans do, while Americans rate themselves as more dominant. These stereotypes may have helped some subjects identify nationalities. Australians who looked friendly and not dominant were more likely to be correctly identified as Australian. Other subjects simply went with the familiar. “I looked mostly for who was ‘American,’ ” one test subject told the researchers. “If they didn’t look ‘American’ I categorized them as Australian.”

Psychologist Paul Ekman says emotional expressivity is modulated by cultural norms. In the 1970s, while studying the facial expressions that Japanese and American college students made while watching unpleasant films, he noticed that their expressions differed only when a scientist was in the room. If so, Americans exaggerated their negative expressions while Japanese masked theirs with a smile. The universal pattern of emotional expression is altered by what we’ve learned about public behavior. In America, for instance, only winners can cry. “Losers,” Ekman said, “must be good sports, so they accept defeat without any sign of major disappointment.”

At least 25 muscles are involved in emotional facial expressions, and each emotion recruits a different combination. The universal displays of emotion tend to use three to five muscles, on top of which different cultures engage extra muscles as nonverbal accents.

The most distinct culturally specific facial expression might be the British smile. According to Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner, compared with Americans, the British tend to use an extra facial muscle when they smile. Americans and everyone else smile using the zygomaticus major, a muscle that runs from the corners of the lips to the outer edge of the eyes. It and muscles around the eyes contract the cheeks, pull the lips upward, and expose the top teeth. This creates an assertive, Tom Cruise-like smile. The British also use the risorius muscle, which runs below the zygomaticus major, to pull the lower lips sideways. The result is a seemingly more polite smile that reveals both the top and bottom teeth—a Prince Charles smile. “If the British win any medals,” said Keltner, “I think we’ll see this smile.”

In the event that this doesn’t happen and flag-wrapped Americans dominate the podium, you can test your own nationality-spotting ability by clicking on the Olympic faces throughout this article. You’re probably better than you think. When you’re watching the games next week, look for the lower teeth on smiling British athletes, an agreeable, big smile on Australians, and on the Americans, an assertive, upper-teeth-only smile that gives off a vague air of dominance.

Bronte Barratt

Australia

Hannah Miley

Great Britain

Paige Railey

USA

Robert Renwick

Great Britain

Goldie Sayers

Great Britain

Chris Hoy

Great Britain

Stephanie Rice

Australia

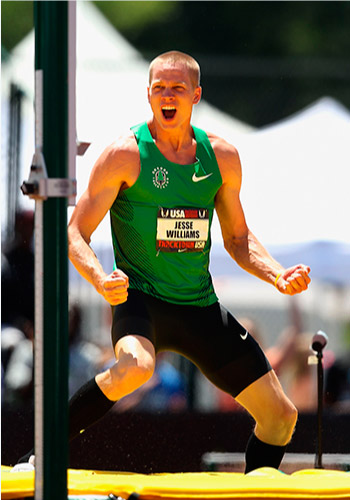

Jesse Williams

USA

Tonia Couch

Great Britain

Bryony Shaw

Great Britain

Lia Neal

USA

Eamon Sullivan

Australia