’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house, not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse. The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, in the hopes that St. Nicholas would soon stuff them with the heavily worn panties of a homicidal female sociopath? Bristle if you will, but there’s no shortage of “collectors” who would happily trade a shiny, new Kindle Fire for the desiccated body parts of a cannibalistic serial killer, a kitschy trinket crafted by hands that once did unspeakable things, or anything else from a scabrous cache of “murderabilia” this Christmas.

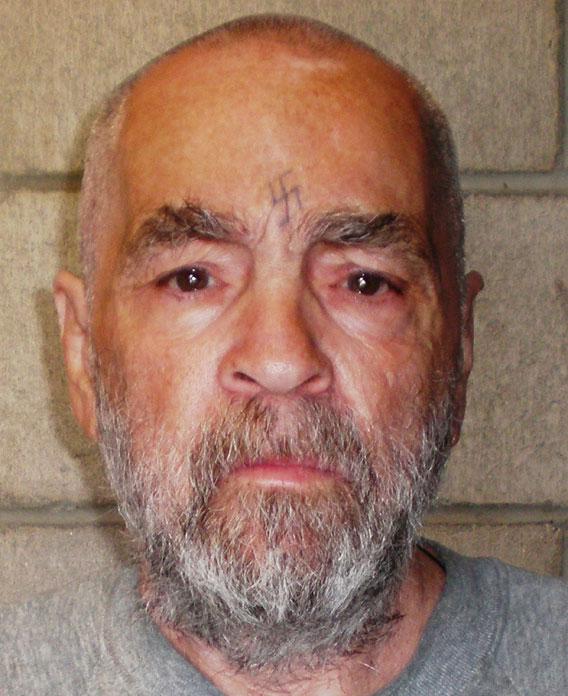

Commerce in evil isn’t anything new, of course. Much to the consternation of law enforcement and victims’ families, the trade in serial killer artwork, tchotchkes, locks of hair, and even nail clippings has been a quietly stable business for years. Prior to his 1994 execution, brisk sales of his notorious clown paintings earned John Wayne Gacy, who sexually tortured and murdered at least 33 young men before burying most of them in the crawlspace of his home, a six-figure jail-cell salary. Over at Supernaught.com (an emporium of “True Crime Collectibles and Memorabilia”), a brief handwritten note from Ted Bundy to another inmate asking for fruit pies from the prison cafeteria can be yours for a mere $3,900, an X-ray of Charles Manson’s spine can be had for $8,500, a strand of hair from “Night Stalker” Richard Ramirez is on sale for the bargain price of $150, and early-20th-century child rapist and cannibal Albert Fish’s autograph is going for a hefty $30,000. Murderauction.com gives such things the eBay treatment: You can bid on anything from boarding-house butcher Dorothy Puente’s handmade earrings (starting bid $380) to a licked envelope from “BTK” killer Dennis Rader (on reserve for $325) to the original license plate from Gacy’s 1978 work van (which apparently just went for $4,999.99). Still can’t find your favorite psychopath’s goodies? There’s always redrumautographs.com.

All this raises the curious question of why such collectors exist at all. There’s the well-known sociological problem of the media’s making stars of serial killers, but the market for murderabilia does seem to be at odds with some basic facts about human psychology. For example, take the findings from a landmark social psychology study published by Carol Nemeroff and Paul Rozin in 1994. Their research showed that most people think of evil as being a physically contagious trait. Participants said, for instance, that they’d be happy to wear a sweater or other piece of clothing that belonged to a loved one or someone they admired, but the vast majority cringed at the thought of donning something once worn by, say, Adolf Hitler. Most went on to explain that they’d refuse to do so even if the clothing were thoroughly laundered; and their powerful aversion would extend to cut-up swatches of this sweater that had been reassembled into a new article of clothing. They wouldn’t even want to touch the burned ashes of such a garment.

Since this initial work, further studies have replicated these findings of magical thinking in the moral domain, whereby someone’s social essence is seen as being communicable via mere secondary contact. To bring this moral contagion effect into the present, imagine running Casey Anthony’s hairbrush across your scalp, or going to bed wearing Jerry Sandusky’s undershirt. Even if we knew these items had been disinfected or professionally laundered, they would still tend to induce some ineradicable sense of disgust.

Victorian-era anthropologists first described such beliefs with respect to various religious rituals, such as witchcraft incantations using someone else’s stolen body parts and, scandalously for the times, mainstream religious rituals such as the Pope’s touchy-feely blessings on the forehead. The Buddha’s left canine tooth, allegedly retrieved from his cremation pyre by a fast-thinking acolyte millenniums ago, has led an even more storied life than its original owner. After thousands of years of bloody wars fought over the tooth’s rightful heirs, it now sits in gilded splendor at the “Temple of the Tooth Relic” in Sri Lanka, where for centuries people have traveled daily to pray to a dead primate’s bedazzled fang. According to George Frazer, whose book The Golden Bough was the first scholarly treatment of superstition across a variety of human societies, such beliefs constitute a form of “sympathetic magic,” which relies on “the mistake of assuming that things which have once been in contact with each other are always in contact.” Too soon, you’ll say—but I wouldn’t be surprised if venerating atheists were already gathering up corporal relics and the personal effects of Christopher Hitchens. I’d certainly want his pen.

The point is that one needn’t believe explicitly that heroic virtues can rub off of discarded body parts, or that evil comes in the form of cooties, to feel a deep connection or aversion to these special objects. As authors such as Bruce Hood, Paul Bloom, and Matthew Hutson have argued, this type of superstitious thinking afflicts rational and irrational minds alike.

And related ideas affect our behavior in domains where we may not expect to see any signs of superstition. Sexual fetishes hinge on the aroused party’s knowledge that a particular object (such as a worn shoe) has somehow absorbed the hidden essence of the person so desired. You may have your own colorful tales, but I’d be lying if I said that I’ve never been intensely aroused by a Diet Coke can. (Back in high school, I pleasured myself to the empty one discarded by a boy-crush.) My own mother once told me that she’d secretly kept a used cigarette butt left in an ashtray by my father before they were married. (I’d rather not think of what she did with it.) In fact, business owners might take note that a recent study revealed potential (straight) customers are more likely to purchase clothes that have been handled by attractive sales clerks of the opposite sex.

A recent study by George Newman, Gil Diesendruck, and Paul Bloom in the Journal of Consumer Research may shed some light on these behaviors. The authors postulate three possible reasons why values soar for objects that were used, owned, or otherwise touched by celebrities, and how this effect is influenced by whether or not these celebrities are loved or loathed. First, it could be that such objects simply evoke positive associations for the collector, transporting him or her to a desired mental place. (For those who view true crime as a sort of impersonal form of “entertainment,” like a horror movie, this could explain the appeal of murderabilia, at least for some collectors.) Second, the collectors might be responding to intuitions about the monetary worth of these items—that is to say, it could be economic sagacity that drives their interest in saintly and evil objects alike, in the hopes of capitalizing on some imagined future buyers’ superstitious beliefs. (That this is a circular explanation doesn’t elude the authors.) The third and final explanation for the behavior is that the buyers are genuinely motivated by essentialist reasoning and contagion beliefs: They’re hoping that the attributes they ascribe to the celebrities, good or evil, will somehow rub off on them from the objects they acquire, or at least that these incarnate objects will give them a type of special access to the celebrity.

In a series of experiments designed to tease apart these competing hypotheses, Newman and his colleagues all but eliminated the first account. If the mere association between famous (or infamous) people and objects drives buyers’ willingness to part with their money, then the degree of physical contact between these objects and the celebrities should be irrelevant. But in fact, when asked to imagine their interest in purchasing various celebrity-owned objects at an auction, participants in these studies were more willing to bid on items that had been in closer physical contact with the celebrity. For instance, when told that, “This sweater was given to Justin Bieber as a gift and it was one of his favorite sweaters and he wore it often,” participants were more willing to bid on the object than were those who’d heard “he never actually wore it.”

This was only the case for celebrities that the participant liked. By contrast—for all you Bieber-haters—bidding willingness decreased with increasing degrees of contact with personally hated celebrities. Yet by highlighting market value (“There is a lot of demand for items owned by this person, so if you wanted to, it is highly likely that you can resell the sweater”) this effect was mitigated such that people were willing to buy objects that had belonged to famous people they didn’t like, and, again, the more manhandling by the despised the better. So there’s an appreciation that, although you personally might not want Bieber’s sweater or Charles Manson’s bracelet, others would—and these others are essentialists just like you, only with a different set of heroes and villains.

The authors also found some intriguing individual differences among the participants. Generally speaking, the foregoing effects were more pronounced for those who scored highest on a “disgust-sensitivity” scale. That’s measured by asking participants how much they agree with statements like, “Even if I were hungry, I would not drink a bowl of my favorite soup if it had been stirred by a used but thoroughly washed flyswatter,” or “If a friend offered me a piece of novelty chocolate shaped like dog poo, I would not eat a bite.” It turns out that the more squeamish you are, the more likely you’ll be to ascribe value to celebrity-owned objects.

All of this leads back to the puzzle of murderabilia. If essentialist reasoning indeed drives the market in celebrity odds-and-ends, then why on earth would anyone want to collect evil objects? Which qualities would they hope to acquire from a teaspoon of dirt that had been collected from the Wisconsin grave of Ed Gein, that tanner of human hides who inspired the character of “Leatherface” in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre? What kind of person would proudly hang a mediocre oil painting by “The Gainesville Ripper” Danny Rolling—who stalked, raped, murdered, and then theatrically posed the mutilated bodies of Florida college students for police—over their cozy guestroom bed?

Although no studies have been done on the special attributes of murderabilia aficionados, one possible lead may be found in a study of gender differences in readers of true-crime books. Inspired by the curious observation that Amazon reviews in this genre seemed disproportionately authored by female buyers, psychologists Amanda Vicary and Chris Fraley conducted a set of controlled experiments confirming their suspicion that women are more attracted to tales of rape, abduction, and murder than are men, who, given the choice, opt for war stories instead. What’s more, books that contain more details about these crimes are preferred over those that gloss over the forensic facts. Vicary and Fraley believe that these somewhat surprising findings can best be understood by the fact that, although men are actually far more likely to be the victims of violent crimes, women are significantly more fearful of becoming victims. So the strategic information in true-crime stories, with hints on survivability, may render them more appealing to women.

Serial-killer groupies are almost always female as well, and some scholars have argued that these women’s obsession with hideously violent men can be understood as an anachronistic evolutionary strategy in which the most fearsome males in society were, in the ancestral past at least, often also the most valuable mates. I don’t mean to insinuate that murderabilia collectors are predominantly women. A murderauction.com administrator informed me by email that last month’s registrations at his site were about 25 percent female, but the online forums are “almost always dominated by women,” at least as he can judge by users’ names. It’s also the case that women score significantly higher than men on disgust-sensitivity measures. Considering this alongside the true-crime findings of Vicary and Fraley, it’s conceivable that murderabilia collectors, both men and women, are actually more fearful of such sensationalized crimes than non-collectors. Perhaps they suffer the subconscious illusion that the moral monster would harm others while sparing them, on account of their unique connection through objects infused with the killer’s essence, a frightening, unpredictable force they are trying to better understand.

Either that, or the simpler, scarier hypothesis—collectors genuinely admire serial killers for what they do.