This article originally appeared in New Scientist.

Stef Conner is a composer, performer, and musicologist with interests straddling classical and folk genres. She is working with a group that recreated an ancient lyre and aims to reverse-engineer music of the second millennium B.C.

Are there any traces of Babylonian music, which hasn’t been heard for more than 3,000 years?

We have the text of lots of poems from ancient Mesopotamia, and it seems likely that some were originally songs of a sort. We have the words, but the music was either not written down or is lost. I thought it would be exciting if we could listen to these poems as they were meant to be heard. The reason I think we can do this is that the language of the poems—their stresses, intonation, and rhythm—provides clues about musical style.

When did you develop your interest in the links between language and music?

My Ph.D. was in composition, with a focus on the ways in which language can be used as musical material. At that time I also played piano with a folk band called The Unthanks. It gave me new insights into how music interacts with language.

Isn’t it a bit of a leap from modern folk music to the music of ancient Mesopotamia?

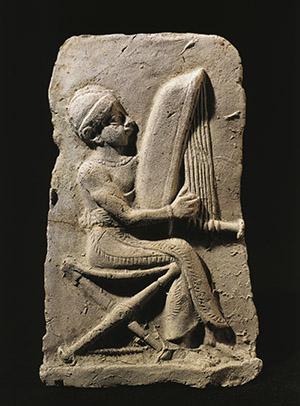

I got in touch with a group interested in lyres and harps, as I am very interested in Anglo-Saxon music. Through them I met Andy Lowings, who organized the Gold Lyre of Ur Project, which built a replica of a 4,550-year-old Mesopotamian gold lyre. He asked me to compose music for the lyre, and last year we recorded the result—an album of contemporary music, sung in Babylonian, called The Flood, out this December.

What about more historically accurate music?

It would be nearly impossible to work with Babylonian poetry and replica instruments and not become preoccupied by the question of what Mesopotamian music really sounded like.

So how would you go about answering that?

I propose to look for features that recur frequently in living music linked to Mesopotamia. The point is to look for the most consistent features in a widely dispersed collection of music. The most commonly occurring will be those most likely to have been features of Mesopotamian music, either because they have been preserved through musical lineages branching out from Mesopotamia, or because external influences have caused them to be invented over and over.

Would the songs be familiar to ancient ears?

You can’t perfectly reconstruct a Mesopotamian song in this way. But I think if you could go back 3,000 years and play it to Babylonians, they would say: “Oh, that sounds a bit like our music.”