Timothy Murphy is a professor of medicine, microbiology, and immunology at the University of Buffalo in New York. He says The genetic secrets of a misnamed microbe, Haemophilus influenza, could help ease a lung condition that affects hundreds of millions of people.

Robyn Braun: You study Haemophilus influenza, or H. flu. This bacterium’s name suggests it causes flu, a viral illness. How did this come about?

Timothy Murphy: It was named during the 1918 influenza epidemic. When pathologists looked at the lungs of patients, they saw a bacterium and named it Haemophilus influenzae, mistakenly thinking it caused influenza. But it was a secondary infection that people contracted as a result of the flu.

RB: Why is this misnamed microbe so important?

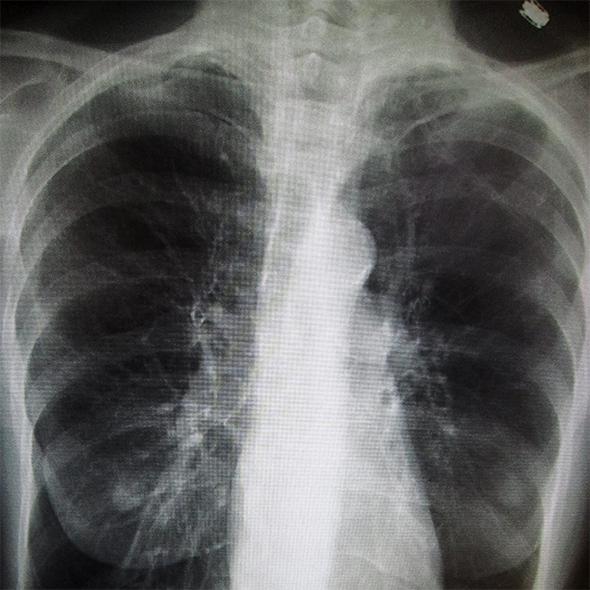

TM: I work with people who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an umbrella term for lung diseases including emphysema and chronic bronchitis. It affects more than 300 million people worldwide. This bacterium has a special relationship with COPD because those with the condition simply can’t clear the bacteria. It gets into their lower airways and can cause infection that leads to serious complications.

RB: You lead the longest running clinical study of COPD in the United States, with a huge collection of H. flu samples. How did it all start?

TM: We enrolled our first patient in 1994. At that time the role of bacteria and bacterial infection in COPD wasn’t well understood. We wanted to enroll people over time and study them and their bacteria to better understand this factor.

RB: Why is gathering many samples over such a long period important?

TM: COPD behaves very differently in different people. Some will have shortness of breath while others will cough a lot but have no shortness of breath. In any study you need large numbers to account for that range. It’s similar for the bacterium. There are tremendous differences among the different H. flu strains and so we need a large collection to make meaningful observations and to find the genes important for causing infection. Now we are beginning to sequence the genomes of these strains and we can see that one strain can differ from another by as much as 20 percent.

RB: You brought about a major shift in clinical understanding of COPD. Tell me about it.

TM: People with COPD might acquire a new strain of H. flu every month, even if it doesn’t cause symptoms. We have learned that it’s when people acquire new strains that they are most likely to see flare-ups in their symptoms. Before that, there was this idea that it simply took a certain amount of bacteria to cause an infection.

RB: What do you hope to learn by sequencing the various genomes in your H. flu collection?

TM: We have three goals. The first is to understand why some strains persist in the airways and others are cleared. The second is to contribute to current efforts to develop a vaccine. And the third is to understand how the bacteria manage to persist in spite of repeated antibiotic treatments.

RB: Examining sputum samples for two decades doesn’t sound like a barrel of laughs …

TM: One time I asked a patient to tell me about the color of his sputum. He said: “Well doc, don’t take this the wrong way, but it’s almost exactly the color of your shirt.” Sometimes you get to laugh.

This article originally appeared in New Scientist.