Gerard ‘t Hooft is a professor of physics at Utrecht University in the Netherlands and a recipient of the 1999 Nobel Prize for theoretical physics. He explains why he is an ambassador for the Mars One project and whether he fancies a reality-TV-funded move to the red planet himself.

Govert Schilling: How did you get involved with a project that sells one-way tickets to Mars?

Gerard ‘t Hooft: The concept fits in with my own ideas about human exploration of space, which I described in my book, Playing with Planets. In fact, the co-founder and general director of Mars One, Bas Lansdorp, once attended one of my lectures. When he asked me to become an ambassador for Mars One, my first reaction was that it will take much longer and cost much more than they currently envision. However, after learning more about the research they had carried out, I became convinced that human flights to Mars could become a reality within 10 years. So in the end, I said yes.

GS: What excites you most about sending people to the red planet?

GtH: Ever since the Apollo program, I have dreamed about human settlements on other worlds. It has to do with our urge for expansion, exploration, and conquest. Yes, as a scientist I realize that if you just want to learn more about another planet, smart robots might be a better option, at least in the foreseeable future. But with this project, the ultimate goal is different. It is about whether we are able to survive in a whole new environment—in a small community and a micro-ecosystem, growing our own food and building almost everything from scratch. In a sense, it will be comparable to what human explorers did in the prehistoric age.

GS: Has Mars One had many applicants?

GtH: So far, almost 40,000 people from all over the world have applied to become Martians. This is many more than I had imagined, although some psychologists and cultural anthropologists had apparently predicted there would be at least a million candidates. Everyone is now being asked about their motivation, and thousands of replies have already been collected.

In January, Mars One secured investments from companies in the Netherlands and South Africa. These funds will be used to set up the astronaut selection program later this year and to finance conceptual design studies.

GS: Wouldn’t you prefer to be involved in a more scientific mission?

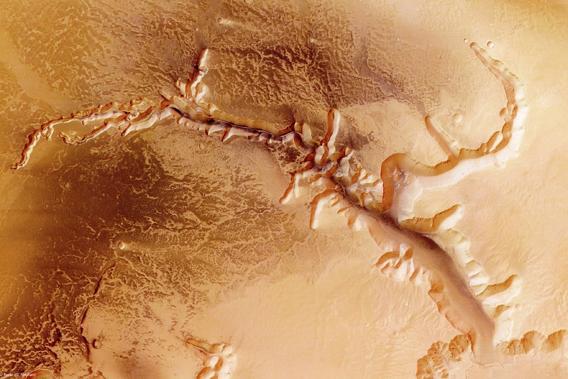

GtH: In a sense, this is a scientific project. There are many scientific questions that need to be addressed, and I am sure there will be plenty of scientific spin-offs, too. A lot of technological research on all aspects of the mission has already been carried out, and many of the major problems have been identified. One of the toughest problems is the radiation environment in interplanetary space. Then there needs to be research into the design of the space suits, the choice of the best location for the outpost on Mars, and the availability of water on the planet, in the form of ice. The plan is to grow food in greenhouses with artificial lighting, powered by efficient solar cells—this will involve a lot of interesting research. The most exciting question might be whether the whole idea is feasible at all. I welcome suggestions and queries from fellow scientists.

GS: How do you feel about being associated with a project funded by reality TV shows? Might you live to regret it?

GtH: Well, if people blame me for it, I have brought it on myself. However, this is the world we live in today—governments are not prepared to finance projects like Mars One, so the money has to come from some other source, and if it is a TV show like Big Brother or X Factor, then so be it.

Then again, I would rather not be involved with the TV show itself. And yes, at times I have asked myself what I have got myself into. After all, it does sound like a crazy plan. But so far, it is still fun, everything is still on track, and there do not appear to be any major obstacles. So I would tell my critics to let the facts speak for themselves.

GS: Would you encourage younger scientists to get involved?

GtH: It would not surprise me if it takes Mars One more than 10 years to put the first humans on Mars, and I can imagine it will cost more than the $6 billion currently envisioned. I have always been careful about those claims. If the project fails, my reputation may sustain some damage, but I am pretty sure I will survive that. Younger scientists, with their careers ahead of them, might run a bigger risk in that respect. Then again, I do not see how it could be held against you if you were to take part in technological design studies or in addressing various scientific issues.

GS: What is the difference between Mars One and the recently announced Inspiration Mars mission?

GtH: The Inspiration Mars Foundation, spearheaded by businessman and space tourist Dennis Tito, aims to send a couple on a return trip to Mars, but they will not land there—it is just a close fly-by. Of course that is an interesting idea, but not nearly as exciting as actually building a colony on another world. I fear it might suffer the same fate as the Apollo program: There will be a couple of flights, then public interest will dwindle.

Mars One, on the other hand, fires our imaginations. The ultimate goal is a community of 20 settlers. In the distant future, the colony will not only expand through immigration, but also through population growth. I realize, of course, it might take some time before the first child is born on Mars—and making the colony childproof will be a challenge, as I am well aware since becoming a grandfather.

GS: Would you volunteer to go?

GtH: I would love to go to Mars, but not being able to return would be a big obstacle for me. Even if return flights were offered in the future, it would be almost impossible for the first settlers to go back: Spending many years in the much lower gravity of Mars will have an irreversible effect on bone and muscle strength. Maybe when I am much older I will not mind leaving Earth for good. My chances of being selected are probably negligible—I would just be a clumsy old man, getting in everyone’s way.

This article originally appeared in New Scientist.