It was a revelation. Germs cause disease. When Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch discovered and developed what would later be called the germ theory in the 1860s, this was a radical, then revolutionary idea—one so good it seems obvious in retrospect.

At the heart of their work was the notion that individual species cause disease by invading our bodies. Over the next century, the notion of “germs” changed our behavior. It led us to scrub our hands and actively fight specific pathogens (as researchers came to call dangerous germs) and to cure the diseases they cause. These changes saved millions, maybe billions of lives. Every day you rub shoulders with the success of this theory. How could there be anything wrong with it?

New research, however, is beginning to question, if not germ theory itself, at least some of the actions we have taken on its behalf. These studies come from very different groups of scientists, largely working separately and apparently without much awareness of one another. But I believe that they are unwittingly part of the slow unraveling of a new, broader theory of disease, the ecological theory of disease.

Here’s the thinking. In the late 1980s, microbiologists and public-health researchers began to notice differences between rural and urban kids. Rural kids seemed less likely to develop allergies. A new idea was floated—perhaps they had been exposed to more bacteria that had helped their immune systems to “balance” themselves. This idea, often called the hygiene hypothesis, has since found support in empirical studies worldwide.

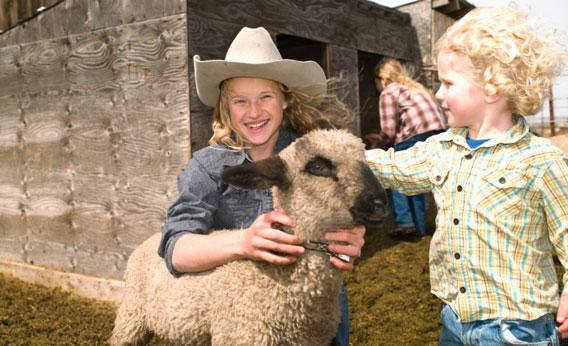

Country kids whose fingers still plunge regularly into the rich bacteria of soil (and farm animals) have fewer allergies. But it isn’t just farm living: Sometimes the exposure to a wilder bacterial life can be subtle. For example, a recent study in Australia found that pregnant mothers living with dogs were less likely to have children with allergies. These studies note fundamental differences between the immune systems of dirty kids and clean kids. Conclusion: In some ways it is better to be dirty.

More recently, a new version of the hygiene hypothesis has suggested that it isn’t just large numbers of bacteria that it is good to be exposed to but, rather, many kinds of bacteria. Our immune system needs to be exposed to many species in order to sort the good from the bad. Without such exposure, argues this “biodiversity” version, mistakes get made. The immune system, in not having seen enough of the world, doesn’t know quite what to attack. It attacks pollen. It attacks us.

This made me sit up and take notice. There are, I realized, many separate fields of science in which the failure to be exposed to good species or even just a diversity of species is believed to make us sick.

The “worm hypothesis” argues that our bodies evolved with parasitic worms as a dependable presence, and that for some individuals the absence of such worms causes the immune system to overreact, leading to autoimmune diseases such as Crohn’s, multiple sclerosis, and asthma. The nature deficit hypothesis, on the other hand, argues that lack of exposure to nature in our city environments causes psychological problems in children who then suffer from any of a variety of behavioral and other problems. This is country cousin to the biophilia hypothesis, which suggests an innate fondness for nature and biodiversity, which both bring us benefits and, in their absence, costs.

All of these relate to the much older and well-accepted “deficiency” model, which correctly states that diseases such as scurvy are caused by the absence of whole classes of species (and their nutrients) in our diets.

What seems to have gone pretty much unremarked is that these ideas all suggest ways in which the absence of beneficial or historically common species in our lives can make us sick. In a way, taken together these ideas make up the obverse of the germ theory of disease; if the germ theory is about bad species being present, these hypotheses are all about good species that have gone missing.

Bringing the pieces of the puzzle together seems to show what I call the ecological theory of disease. This is the idea that illness can arise from the presence of species that negatively affect our health or the absence of species that positively affect our health.

Of course, to ecologists and evolutionary biologists, such a theory is not exactly news. We can all hold up long lists of species that require other species, their partners and neighbors, to survive. Think corals, lichens, leaf-cutter ants, tube worms, bean plants. Now think humans. Take away the species we benefit from every day and we would die in many different ways.

The point is that public-health researchers, medical researchers and doctors don’t think like ecologists. Hospitals only consider other species when they are “bad,” when, that is, they are behaving as germs. With a couple of examples we tend to regard as freakish (the medical use of leeches or fly maggots), doctors almost never prescribe the apple, bacteria, worm, or other sort of “nature” your body is “missing,” though if you took just the right mix it would surely help keep the doctor away.

So what should we do? If the germ theory of disease tells us to hunt down, scrub off and otherwise avoid bad species, the ecological theory of disease suggests the same, but that we also need to figure out how to attract, farm, and nurture beneficial species. Fine. But there is a big problem: While we have spent the last 200 years chasing down bad species, we have spent far less time hunting good ones. Worse, while there are hundreds of pathogens that affect our health and well-being (with a small handful being the really deadly monsters), the precise mélange of beneficial species we need could involve hundreds of thousands of species—or more.

Those species do not always have names. Recently, I cataloged the species on my body and my house, finding more than 2,000 species, most of which most experts could not identify. Which ones were good for me? Who knows? What is worse, no one could tell me which good species I might be missing.

More and more, we seem to “know” that we need nature. Many of its species benefit us, but we are not yet smart enough to know which ones. We are left to wait for the systematists—those catalogers of life—to find and name the species on our behalf. And then we will have to wait some more for the ecologists and evolutionary biologists to study those species. Only then, finally, will medical researchers begin to weigh up which ones we need and which ones we don’t. But it will take a while.

We have neglected the book of life for so long that at our current rate of research, without investment in projects larger than any yet imagined, much less implemented, we won’t catch up for hundreds of years. Meanwhile, some of the species we are losing from forests and wild lands (or just from our modern lives) could easily be the ones that help to make us whole.

If we only knew which ones.

This article originally appeared in New Scientist.