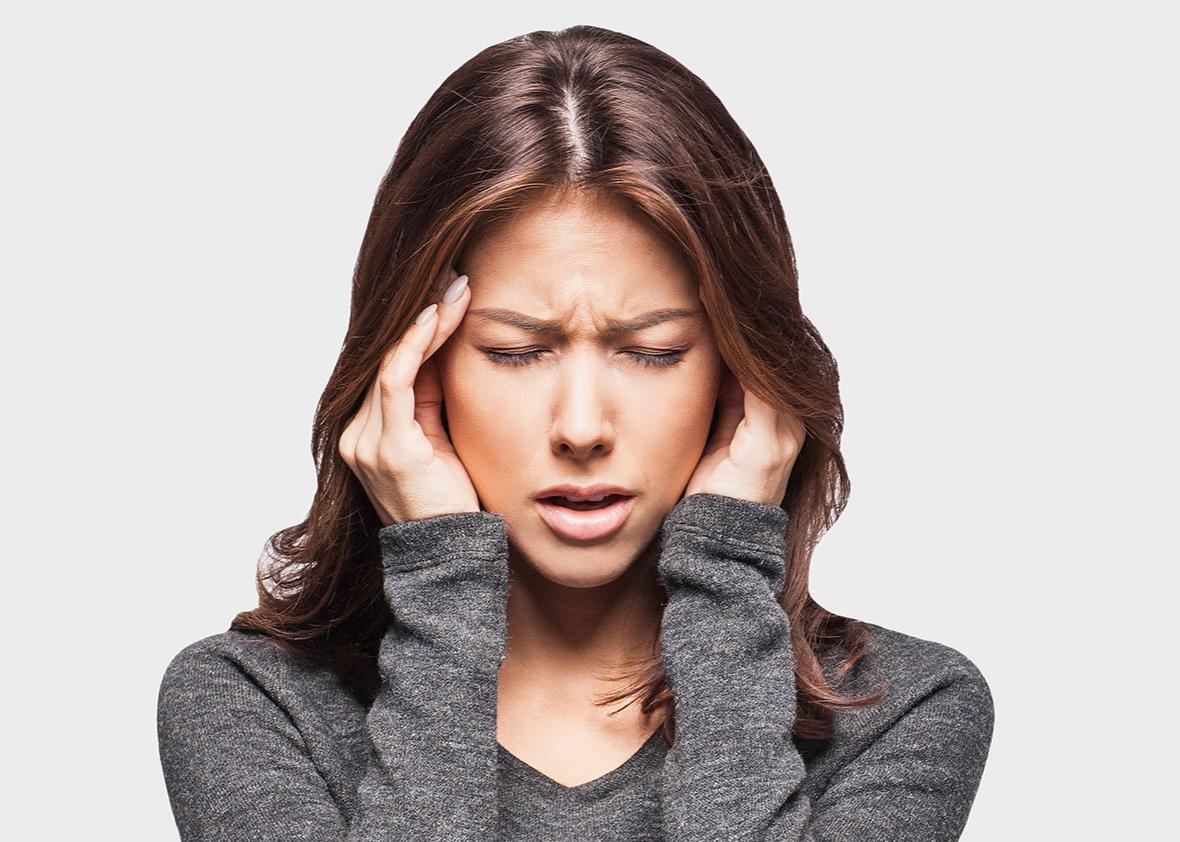

Stock photos are ubiquitous—and infamous. The concepts are often laugh-out-loud absurd. The models are disproportionately white, not to mention atypically young, beautiful, and able-bodied. Outdated gender norms seem to be readily reinforced. Article after article has shown that stock photographs generally suck. But the place where the limitations of stock photography are most obvious—and deserve special scrutiny—is in depicting mental and physical illness.

The area of most egregious offense is mental health (no surprise there). In stock imagery, almost everyone with a mental health issue can be reduced to a person, on the floor, with their head in hands. “Headclutcher” images are often “tagged” as representing multiple mental health issues, from depression to obsessive-compulsive disorder, but there are some subtle subcategories, too. When I looked at these images on iStock and Shutterstock, two of the most popular stock photography sites on the web, I was struck by the difference between “head in hands with face obscured,” which seemed to indicate shame, and “head in hands with face visible,” which seemed to indicate some kind of internal struggle. Mental illness and depression featured a mix of both subcategories of the trope, but “head in hands” tagged as “addiction” really laid the idea of shame on thick.

iStock

Even if you don’t think it’s offensive (“Oh, it’s just a photo!”), many people do, especially those who are actually living with mental illness. The “headclutcher” theme and emphasis on psychic pain has been derided as a hackneyed approach to depicting the true diversity of mental illness. Get the Picture is one of several campaigns that aim to improve mental illness–related stock photos by providing better alternatives for free. It began in part as a reaction to the head-in-hands image trope, according to Rehaan Ansari, a medical student and model for the campaign:

The “headclutcher” is an unfair and inaccurate representation of what life is like with a mental health condition, but it’s often the image most commonly associated with people who experience them. It’s definitely time to change the backward attitude that mental health conditions are something to be ashamed of.

iStock

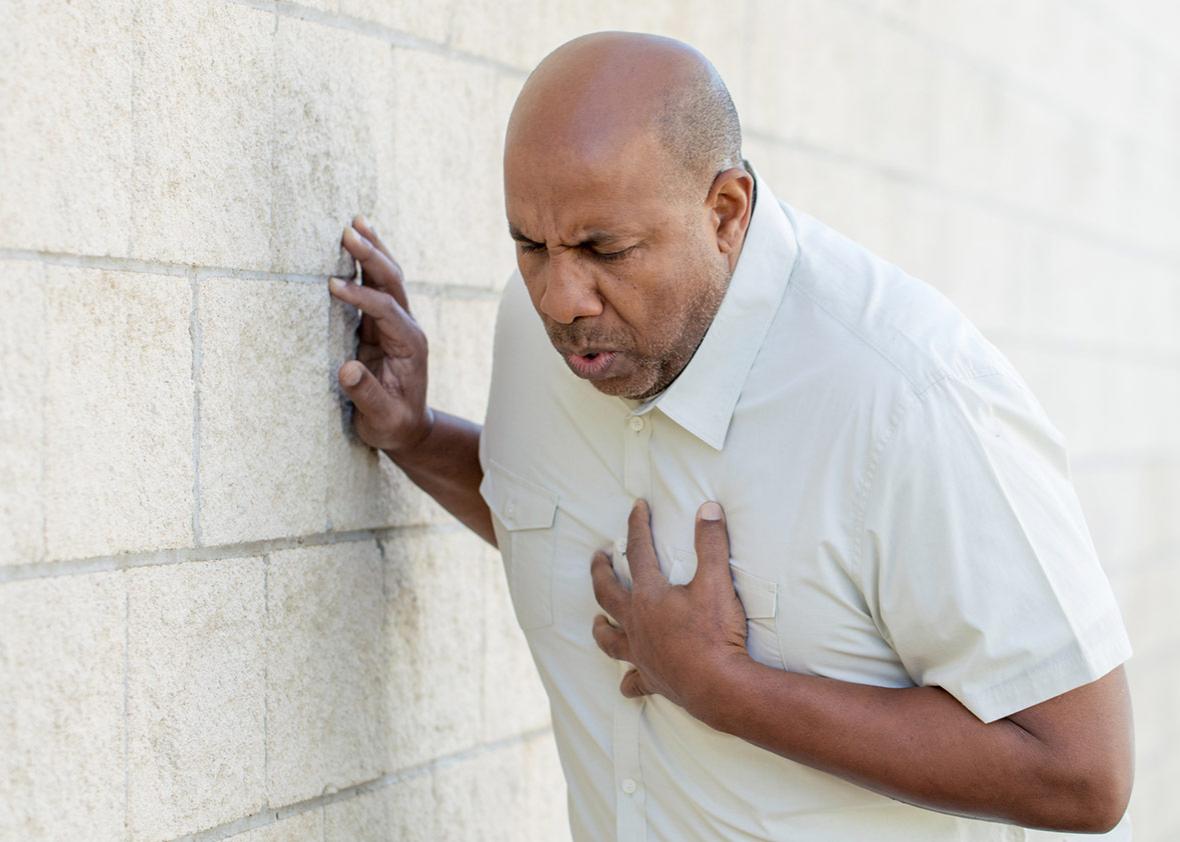

Physical illnesses and medical procedures are also dominated by a few visual themes. Search results for “cancer” on Shutterstock are dominated by women in groups wearing pink and grinning while “cancer” on iStock turns up images of women with their heads wrapped being comforted by loved ones. Photographers have similarly agreed on grabbing your lower back as the universal sign for kidney disease and grabbing your chest as the international image of a heart attack.

iStock

Surgery, meanwhile, is divided into a few camps: well-lit Grey’s Anatomy–style operating rooms; plastic surgery patients with Sharpie-lined skin; and a few close-ups of real surgeries—and the requisite blood and guts. Epidemiologists, meanwhile, have criticized the use of stock photography that emphasize large needles or feature crying children. While it might not look like much to you, experts worry it may dissuade people from getting vaccinated or reinforce the anti-vaccine attitudes people already harbor.

Still, the strangest results are definitely back in the mental health realm—for OCD. This query turned up an unusual number of images of people staring at their hands and chewing on their nails. While there are probably multiple factors at play, the reliance on this trope seems pretty simple: Nail biting is the most photogenic manifestation of OCD, so it’s popular with photographers.

iStock

Rich Legg, a stock photographer and stock image moderator, says the need for simplicity and some semblance of universality is precisely what makes stock photography so challenging. The whole goal of the industry is to create functional stereotypes. But stereotypes aren’t cool anymore, which has left stock photographers scrambling to create representative images that are infinitely applicable, but not so reductive they become offensive.

When it comes to OCD, that problem becomes quickly apparent. Nail biting is much easier to imagine than abstract issues like “compulsive thoughts.” So even though compulsive thoughts are much more central to an OCD diagnosis, nail biting quickly dominated our visual language for the disorder. (Maybe that’s for the best, given one top search result is a “comedic” take on OCD: A man cutting his lawn with kid-size scissors, ostensibly to make every single blade of grass the same height.)

We seem to increasingly agree that many stock photographs are silly at best and harmful at worst. But what do we do about it? While Legg says change won’t be easy, it’s already underway. In recent years, he and others have shifted their focus away from simple, pretty photos and instead prioritize photos that look realistic. A few years ago, Legg says he would call up the local modeling agency to get glammed-up 19-year-olds to play scientists in a rented lab space. But now he’s more deliberate about finding age-appropriate actors and doing additional research before potentially sensitive shoots. These days, he tries to take it one step further, using real people in some of his photoshoots instead of actors. A few years ago he was careful to ask a friend in nursing to advise on a photoshoot featuring an able-bodied girl in a wheelchair, but on a more recent shoot, he just asked someone who uses a wheelchair in real life to serve as his model.

Whether these more conscientiousness images are purchased and used at the same rates as their more stereotypical (but still commercially successful) counterparts remains to be seen. Because that’s the thing about stock photography: It’s not enough for photographers to simply change what they photograph, though that’s important. The real change has to come from the consumers, the people for whom these images are made. To ensure respectful and diverse photos, photographers will have to continue the self-reflection and experimentation—and we’ll all have to work a little harder to deconstruct the stereotypes we have in our heads.