Deaths from drug overdoses have recently multiplied in the U.S., to the point that overdoses are reducing average life span for several demographic slices of the adult population. Opioid abuse is being blamed as the main killer. Doctors’ narcotic prescriptions led to a glut of prescription pain pills in people’s cabinets, which often lead to abuse, and then use of less expensive street opioids that are even more dangerous than prescription drugs.

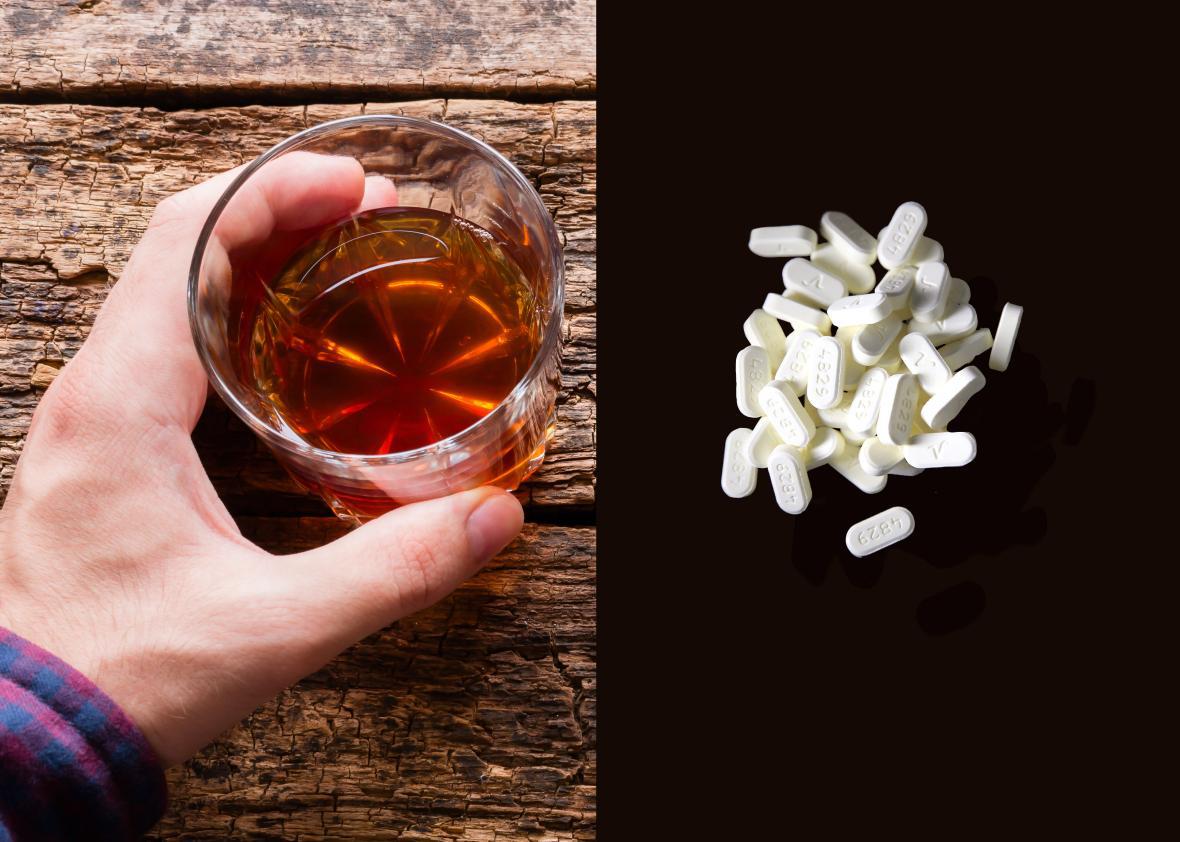

Efforts of law enforcement and treatment programs have focused on opioids and opioid-manufacturers. But this ignores a critical component of this toxic equation: Opioids are not the only substance to blame. Sleeping pills and alcohol often join to make the combined gang a killer. A whiskey bottle does have a government warning that alcohol “impairs your ability to drive” and “may cause health problems,” but it fails to warn that mixing alcohol with narcotics and sleeping pills or tranquilizers can make a lethal combination (also, alcohol overdose by itself can kill). Like opioids, sleeping pills come from manufacturers who have not warned doctors and patients of the great risks. Many sleeping pills are acquired illegally. And prescription sleeping pills, as well as alcohol abuse, have all increased in the past 10–15 years, just as opioids have. (By “sleeping pills,” I refer mainly to the benzodiazepine-agonist hypnotics, most popularly zolpidem, eszopiclone, and temazepam in the U.S.)

A Food and Drug Administration–supported study estimated that in 2011, 31 percent of opioid overdose deaths also involved a benzodiazepine (either a sleeping pill or a tranquilizer). Other estimates of the percentage of opiate overdose deaths associated with benzodiazepines were higher. The 31 percent likely underestimated multiple drug participation because about 25 percent of overdose death certificates did not list all of the drugs involved. Likewise, that 31 percent did not include the most popular sleeping pill, zolpidem, which acts like a benzodiazepine although its chemical structure has a different name.

Zolpidem has frequently been reported in overdose deaths and increasingly causes emergency room visits. When mixed together, zolpidem, similar sleeping pills, and tranquilizers as well as alcohol increase the lethality of opioid overdoses. These drugs gang up to stop breathing. More than 20 percent of the emergencies involving a benzodiazepine also involved alcohol. Many overdose deaths involving sleeping pills and alcohol did not even include an opioid.

Declaring an opioid emergency overlooks a large part of the problem. State governments have passed over the other substances while they sue opioid manufacturers and regulate opioid prescriptions. States do tax and restrict alcohol sales, recognizing that alcohol causes deaths and much damage beyond overdoses. But even though states often even pay for sleeping pills (through Medicaid), they have taken no actions to reduce their overuse. Sleeping pills cause much death and damage besides overdoses—they have been associated with falls and accidents, and cause infections and depression. The public receives almost no warning of the most serious risks.

A much greater effort is needed to protect the public from the risks of combining opiates, sleeping pills, and alcohol. Government publicity, teaching materials, courses, and treatment programs for doctors, patients, and the public should all emphasize the risks of the drug combinations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines and FDA drug labeling warn about combining opiates, benzodiazepines, and alcohol, but have failed to warn about the risks of combining opiates with zolpidem or eszopiclone, which constitute about 75 percent of the sleeping pill market.

Regulators have a role here too—they should give the same attention to sleeping pills that they give to the opioid and alcohol killers. The Drug Enforcement Administration, the FDA, state authorities, and police should all realize that the overdose epidemic is not isolated—it often results from multiple drugs being allowed to work together. If we are working to stop one, we should work to stop all three.