Twenty-one months ago, presidential hopefuls from both parties descended on New Hampshire ahead of its primary, hearing in town halls and debates the same thing again and again: Save us. These voters cared little about plans for tax reform or the threat of ISIS. Instead, they asked potential candidates how they plan to tackle the opioid epidemic devastating their communities. There was no time to waste.

Thursday, nearly a year after his election as president, Donald Trump announced that the worsening opioid epidemic is a public health emergency—a far cry from declaring a national emergency, as he promised he would do at the recommendation of the advisory commission he created. What his lesser announcement means is that for the next 90 days, federal agencies can more freely use existing money to mitigate a crisis that currently kills seven Americans an hour. It does not include any additional funds. (Recall that the Zika virus was contained thanks to Congress’ approving an additional $1.1 billion in emergency funds—a fraction of what the opioid crisis needs.) The announcement has been celebrated by some as an important step toward raising awareness, but its ability to make a tangible impact is extremely limited.

If you can say anything about the opioid crisis, it’s that we’re aware of it. September was National Recovery Month, and with it came numerous projects by news outlets dedicated to showing us a worsening overdose crisis whose images we have by now become intimate with. Glamour’s 11-chapter “Women and Opioids” opened with a reconstructed scene of a young woman shooting up in her bathroom, only to immediately realize she was overdosing. The Cincinnati Enquirer delivered a deeply reported tick-tock, “Seven Days of Heroin,” which deployed some 60 reporters, photographers, and videographers around the Ohio city and its surrounding communities to show readers “what an epidemic looks like.” The New Yorker this month ran a photo essay about overdoses in an Ohio county, describing the deaths as having “become impossible to ignore.”

These projects are increasingly hard to stomach. Writer William S. Burroughs brutally portrayed the sicker side of heroin in his 1953 novel Junky, back when writing about drugs was literarily transgressive. By this point in the crisis, these scenes can feel sensationalized—doing more to stoke an emotional response than a spur to action. What does documenting “seven days of heroin” do, if it doesn’t also engage with how we could mitigate the death toll? How many times should we explain how we got here, without looking toward how we should get out?

I kicked heroin five years ago as a lanky, depressed 22-year-old. Since then, I’ve turned to research and journalism, obsessively trying to figure out why opioids kill more Americans year after year despite us being constantly told that all hands are on deck, from local activists to epidemiologists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still, annual heroin deaths have more than tripled since I kicked it in 2012. Heroin use increased the most—by more than 100 percent—among 18- to 25-year-olds from 2011 to 2013. I can pull out lots of numbers like this, but I doubt any of them will surprise you—after years of increasing pressure, we are finally, mind-numbingly, aware of the problem. The question, though, of how to solve it remains. We have good ideas, most of which are thoroughly outlined in the 2016 surgeon general’s report on addiction, which was mostly echoed by Trump’s recent opioid commission. Trump’s team is set to issue more formal recommendations next week, but given Thursday’s disappointing announcement, there is little sign this is a federal government moved to make the changes we need, whatever plan the commission announces on Wednesday. So the question becomes—the question that keeps me up at night—is: Can we force it to?

* * *

The opioid epidemic mirrors the AIDS epidemic in the scope of its tragedy. Both are stigmatized conditions, thought to only infect other people. Tens of thousands died before then–President Ronald Reagan made a peep about the virus—it was activists from ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, who forced his hand on the issue. Every day that his administration ignored its cries, ACT UP vowed to make a stink. And it did.

ACT UP got what it wanted. It fought for legislation and medical research to develop treatments, and now people with AIDS live long, healthy lives.

Both medicine and legislation are required to mitigate the deaths and harms of the overdose crisis. Both could be the focus of political activism. But there are a few major roadblocks to any kind of activist movement arising among the recovery community today. Our treatment is so bad, for one, it leaves an incredible number of people unequipped and disempowered from making their voices heard. And those who don’t end up needing clinical treatment have less motivation to speak up.

An ugly secret about the way America treats addiction is finally unraveling: It’s laughably unscientific, bordering on cruel. For one, there’s the cost of health care. The only reason I’m alive to write this is because my family provided me with what’s called “recovery capital.” My parents paid, out of pocket, tens of thousands of dollars to get me help. And even with their help, I was still treated at one of the most reputable facilities with outdated, confrontational therapies that tried to shame and embarrass the addiction out of me. In a two-year span across several states, I went to detox, outpatient, sober living, back to outpatient, then detoxed in a residential facility where I lived for 90 days before moving to a halfway house and finally back to sober living. Round and round. I learned more about how to kick in rehab by borrowing my friend’s copy of Albert Camus’ The Stranger than I ever did from reading Alcoholics Anonymous–approved literature.

It’s a Kafkaesque ritual that has gone mostly unchanged since the 1950s, when the abstinence-based model of AA was first designed to treat cases of severe alcoholism. Today, a growing number of addiction specialists are rightfully critical of applying the abstinence model to people with an opioid use disorder. Mark Willenbring, former director of treatment research at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, thinks it’s downright dangerous. “What do people do when they leave these places? They overdose and die,” he told me. Last year, I wrote in Slate how the majority of treatment centers withhold lifesaving medications such as methadone and buprenorphine, the only known treatments that have evidence backing their potential to cut mortality rates in half.

While the industry is finally being called out as a charlatan-filled racket, where hucksters committing insurance fraud abound, the whole residential model is flawed. “You don’t treat a chronic illness with 30 days of intensive rehab—that’s absurd,” said Willenbring, who after leaving the NIAAA started his own outpatient clinic in St. Paul, Minnesota. “These rehabs have ignored decades of taxpayer-funded research,” he told me. Research points in Willenbring’s favor. Studies repeatedly show residential rehab has no clinical benefit over less expensive outpatient settings that treat patients in their own communities. A widespread misconception among Narcotics Anonymous, the de facto support group for people with heroin addiction, is that being on methadone or buprenorphine means you’re not in “real recovery,” a nebulous distinction that sounds a lot like a Calvinist quest for purity and abstinence.

Maia Szalavitz, journalist and author of Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction, has written about addiction and recovery for decades. She told me that like most movements, a lot of time in recovery advocacy is spent, unproductively, fighting one another. For example, the recovery community was against syringe-exchange programs during the AIDS epidemic, which Szalavitz says speaks to a long-standing rift between the 12-step, abstinence-based community and harm-reduction groups.

People who have co-occurring mental health disorders, especially ones that require medication, or who use treatments such as methadone and buprenorphine for opiate use disorder don’t always feel welcome in the recovery community. “I go to AA, but I was not allowed to share at meetings when I was on medication-assisted treatment,” said 47-year-old Francesca Kennedy, who has been going to meetings for more than 20 years in New York.

That the recovery process itself is so difficult means that even people who go through the process and succeed may not find clear communities on the other side—many people, rather than seeing the process as a badge of honor, instead remember it simply as something they endured. But according to oft-cited reports, there are about 23 million Americans “living in recovery.” It’s a huge number of people, most of whom should share common goals. So why aren’t we hearing from them?

One unique aspect of the opioid epidemic is that nothing united this group of people to begin with. Addiction affects all kinds of people, from all social classes, education levels, races, etc. Little is known about the political leanings of “people in recovery.” It’s likely they fall all over the map. While much attention has focused on the overdoses that cluster in rural areas affected by automation and deindustrialization, regions that overwhelmingly voted for Trump, overdoses appear to be happening everywhere.

Of course, that 23 million number includes all drug and alcohol use. There are obvious similarities between these experiences. Often, people with different kinds of addiction run into one another in rehabs and support groups. Someone who was addicted to stimulants can recover right next to someone who was addicted to heroin. It’s tempting to think that whether alcohol or heroin brought someone down, there is a shared experience over which people in recovery bond. But the extent to which this group can be unified at all has been a question among recovery advocates for decades—the most revered of whom is recovery historian William White, who has written more than 300 articles and 17 books on addiction, treatment, and recovery since 1969.

White has studied the identities of people diagnosed with substance use disorder and found three big, though not mutually exclusive, identity styles. According to White’s research, there is the loud-and-proud crowd for whom addiction “has become an important part of their personal identity.” Opposite this group is those who have internalized stigma: “Those whose addiction/recovery status is self-acknowledged but not shared with others due to a sense of personal shame derived from this status.” Between the two poles is a group who holds “recovery-neutral identities,” those who do not self-identify as alcoholics,” “addicts” or “persons in recovery.” (Depending on the situation, I probably straddle the neutral and proud groups.)

Forthcoming research led by John Kelly from Harvard’s Recovery Research Institute (which White collaborated on) adds concrete numbers to these three identities. The articles are still under peer review, but Kelly, the university’s first endowed professor in addiction medicine, told me they found 22.35 million Americans have resolved their drug or alcohol problems—close to the previously reported number. “Roughly half of those (46 percent) adopted a recovery identity,” Kelly said. This could be the loud-and-proud group, who may have had more severe addictions. “The other 54 percent did not adopt a recovery identity,” which could comprise a mix of the neutral or internalized-stigma group.

What are the implications of these findings? Kelly explained that those who’ve adopted the strong pro-recovery identity tend to be the ones who’ve had more severe addictions that required treatment. Kelly described this identity as self-preservative: “You have to remember you have a problem to stay in recovery from; otherwise you’ll be in trouble. There’s a lot more at stake with the severely addicted.” This is the group we think of when we imagine people struggling with addiction—but they aren’t always the loudest voices. For them, simply being in recovery is work enough, or even disabling. If you ask someone who’s been through an addiction that awful, he or she will tell you feeding it had become all-consuming.

But the most interesting finding of Kelly’s is that more than half of the 22 million people who resolved their addictions did so without utilizing any formal treatment or medications—not even self-help by way of AA. (This could explain why so many people don’t adopt recovery identities.) Previous epidemiological surveys have found similarly high rates of what’s called natural remission, or ending addiction with little to no help. We typically don’t hear stories from this group, which explains a stubborn misperception that if you had an addiction, it must have caused significant life problems and that treatment was necessary to beat it. That’s simply not the case for a majority of us.

White told me that any organizing movement “would have to acknowledge the legitimacy of a broader variety of [recovery] approaches, which is slowly happening.” Slow, indeed. Stigma likely plays a role in keeping even the neutrally identifying group from being vocal. But it’s also that these people don’t share their stories because they stopped using before their lives imploded. I know a dozen or so people with this kind of anti-climactic story, some I did heroin with or others whom I watched walk around dazed and forgetful from too many benzodiazepines. They recovered naturally and mostly unscathed. And they don’t talk about it today because, frankly, they don’t have much to say. This is the real, albeit less juicy, story shared by many of us who move through addiction. It’s hard, at this point, to imagine them marching in a rally.

* * *

If there are going to be activists, we may soon start to learn their names. One of the first “stars” might be Ryan Hampton, who directs social media for the addiction advocacy group Facing Addiction. I first heard of Hampton in January, when he mobilized a digital army against Arizona state Rep. Kelly Townsend. In a Facebook post, Townsend had blamed a spate of celebrity deaths—George Michael, Prince, Carrie Fisher—on their “druggie” lifestyles. Hampton screen-grabbed Townsend’s post before she deleted it and posted the insensitive status alongside Townsend’s name, work phone number, and congressional email address. Hampton then asked some 90,000 people who liked his page “to stop what you’re doing and call Arizona Rep. Kelly Townsend.” Within hours, after a barrage of calls and emails, Townsend clumsily walked back her comment blaming a chronic medical condition on the poor lifestyle choices of celebrity “tweakers.”

Hampton, a former heroin user who identifies as being in “long-term recovery,” is good at this kind of thing. In White’s rubric, he fits neatly into the loud-and-proud category. Hampton described his own rehab experience to me as a horror show: He wound up on never-ending waitlists and was rapidly detoxed off methadone, a dangerous move that goes against evidence. When I asked his mother to describe that time to me, she said, “I’m a teacher, a single parent. My resources are limited. … I helped him as much as I could squeeze an onion.” She searched until eventually finding a rehab center in Pasadena, California, that would take Hampton on a sliding scale.

Facing Addiction sees itself as providing a voice for the community, and that often means amplifying their voices on social media (they also have a blog for people to share their stories). In January, Jim Hood, who co-founded Facing Addiction in 2012 after his 20-year-old son died from an accidental overdose inside his dorm, posted a scathing indictment of Sephora for carrying a line of eyeshadow called “druggie.” Hood implored the company to “meet with leaders of the recovery movement and join us in facing addiction.” A social media pack led by Hampton digitally stormed the cosmetic brand, and Sephora apologized to Facing Addiction via tweet and stopped carrying the product.

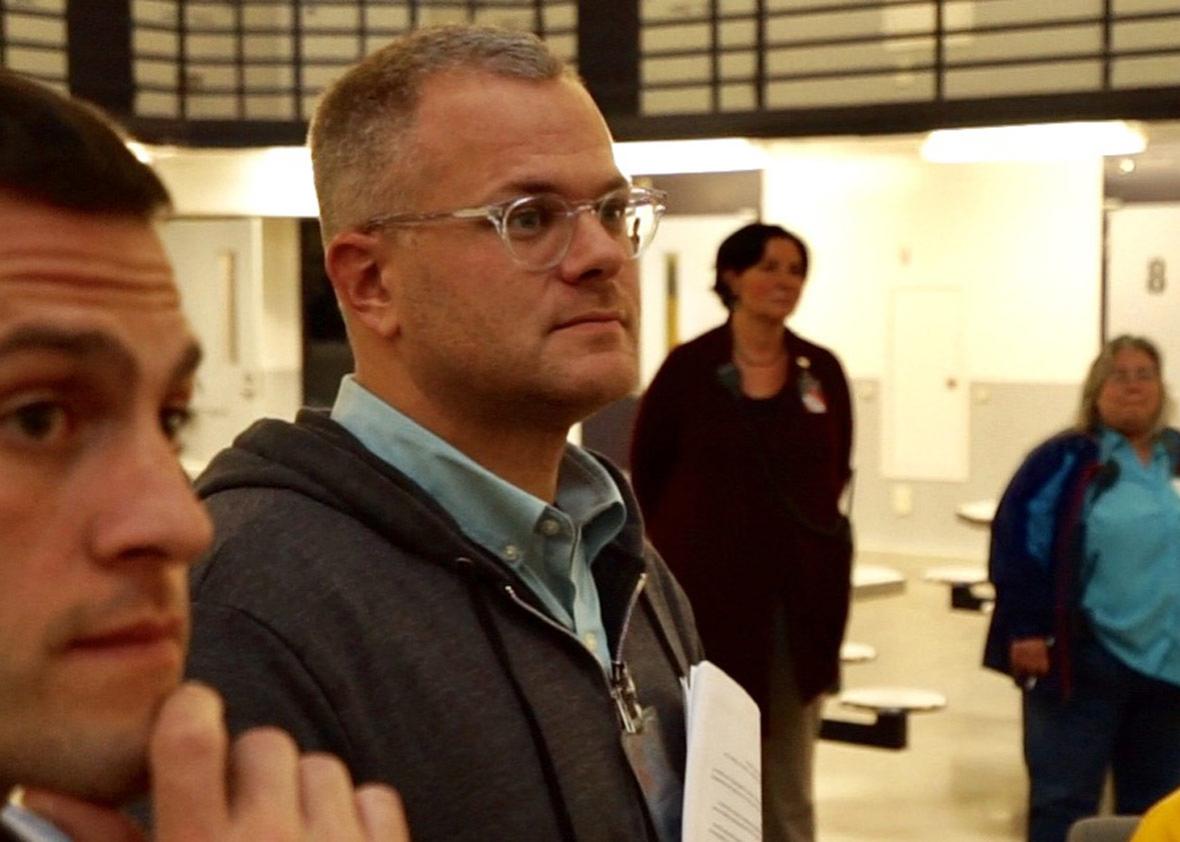

But social media campaigns, while self-expressive and cathartic, are one thing. Having a group as diffuse as “people in recovery” fight for specific policies that meet their needs is something else entirely. Facing Addiction has become increasingly successful in its effort to build bridges in a fragmented field. It’s uniting the treatment community, for instance, over holding facilities accountable to track outcomes, which few currently do (Facing Addiction also partners with dozens of rehabs). Hampton and his work partner, Garrett Hade, met in rehab, and they’re now traveling around the country broadcasting local efforts to address addiction—everywhere from inside jails and prisons to suffering communities in Ohio. Instead of working in church basements, the organization takes the opposite approach, being intentionally loud and visible in its attempt at reducing the human cost sapped by a stigmatized illness, one that people still think of as a sin or crime.

Hampton’s own rise to prominence—his personal social media accounts now reach some 4 million people every month—is hardly apolitical. He began in earnest when he was elected as one of 551 delegates that California would send to the Democratic National Convention in 2016. To secure his spot, he herded some 70 people in his Pasadena recovery network—mostly twentysomethings fresh out of rehab—to the delegates breakfast, a political event open to all voters to select the state’s delegates. Few from Hampton’s crew had ever voted before; some hadn’t been registered until Hampton nudged them along. To get enough votes, the group fanned out among the liberal California crowd and shared how they were trying to beat addiction, or at the very least their attempts to beat addiction, and that Hampton’s goal was to make recovery part of the political dialogue during the election. He won by a landslide.

This should serve as ample evidence there is hunger for the recovery community to build, well, a community, and to raise their voices together. But the question remains: How should it be done? Though a Democrat, Hampton is nothing if not willing to play nice with others. He says he gets beat up on his social media all the time for criticizing Trump (he will message those people back and try to explain that his attacks aren’t personal). “No doubt the Democratic Party platform has been very strong for us, but we live in the age of Trump. We live in the age of a Republican Congress. We need Republican support,” he told me. In early August, he teamed up with none other than Jeb Bush and Dr. Oz to co-author an op-ed in HuffPost imploring the president to declare the epidemic a national emergency. Despite this week’s slow steps to start to take action, it feels worrisomely possible that, along with the dearth of other policy accomplishments of the Trump administration, the overdose crisis will simply continue to get the short end of the stick.

That is, unless, the people and the loved ones of those people, who the crisis hits the hardest, start to make some noise. Despite the heterogeneity of the millions in recovery, Harvard’s John Kelly is optimistic about Facing Addiction’s political organizing. “Even if you took 1 percent of that 11 million who identify as being in recovery, who are real go-getters, hardcore activists, you still have around 10,000 or 11,000 people,” he said. Referring to Hampton, he said, “Imagine if you have 11,000 folks like him, duplicates of him out there—that could instigate a lot of change.”

* * *

But the problem that faced HIV/AIDS activists is a similar one now facing the larger recovery community: For everyone who joins it, there are others who don’t survive to be their own advocates. In August, Hampton texted me that a friend of his, whose recovery efforts he was sponsoring, had died of an overdose in a Pasadena sober house. Naloxone, the drug that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose, wasn’t available in the house. Not having naloxone available in a sober house is like running a hospital without a defibrillator. Worse still, some facilities choose not to keep naloxone around because they incorrectly think it “enables” or “encourages” using.

Hampton’s sadness boiled into anger. “His death was 100 percent preventable,” he said over the phone. “It costs $1,500 a month to live there. The owner and operators should have naloxone on hand and know how to use it.” (His response as an organizer was to invite Missouri harm reductionist Chad Sabora to California to distribute naloxone and train sober houses and treatment centers on how to use it.)

Overdoses leave loved ones behind—loved ones who are part of the group of people whose lives are intimately connected to the recovery movement and who may be persuaded to vote for political candidates who make real solutions a priority. Parents of overdose victims have started grief groups, such as Broken No More, and in the process have become powerful voices in addiction advocacy. The GOP’s thwarted attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act this year, if they had passed, would have likely stunted efforts to curb overdoses. “It could’ve rolled back years, if not decades, of progress on this issue,” Hampton said.

Given this, Hampton still believes Republicans can help solve the crisis: “Yes. Clearly, they’re in power,” he said. “The president campaigned on it. They have the capacity to do this.” But, he adds, “Whether or not they will actually take advantage and do the right thing is yet to be known.”

In the press, the overdose crisis is constantly referred to as one of the only issues left that has bipartisan support. But what if one party is actively working against evidence-based solutions? Take, for instance, Indiana social conservatives who recently shut down a syringe exchange program. What if activism actually needs to be partisan? Other countries have been where we are with rising overdoses; by using a combination of harm reduction tools, criminal justice reform, and modern medicine, they were able to solve their own drug crises. That progress is detailed in a recent report by the Global Commission on Drug Policy called “The Opioid Crisis in North America.”

But much stands in the way or even threatens similar progress from happening in America. Our obsession with incarceration is one: The Massachusetts Department of Public Health found the overdose death rate is 120 times higher for people released from prisons and jails in its state. A whopping 46 percent of federal prisoners, disproportionately nonwhite, are in on drug offenses. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has indicated he favors policies that would renew the failed “war on drugs.”

We need mental health care and better rehab, but we also need more education and understanding. Columbia University’s Carl Hart, who teaches a course on drugs and behavior at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility, refutes politicians’ convenient calls for more “beds.” Hart points out that most of the people dying are combining opiates with other sedatives, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines. “They are dying from ignorance, not the drugs,” Hart said. Another factor causing a spike in overdoses is überpotent, illicit fentanyl, which can be deadly even for more experienced users who have an opioid tolerance. Dan Ciccarone, the lead investigator of a study called Heroin in Transition that tracks America’s heroin supply, told me we’re no longer in an opioid crisis—he calls it a poisoning crisis.

But all these solutions as outlined—criminal justice reform, affordable health care, changing the way substance use is stigmatized in society—are not being pursued equally by the two major political parties. And the party endorsing them as solutions is not the party in charge. It may seem uncouth to take a movement that is gutting the entire country and acknowledge that only the Democrats have a platform set up to combat the crisis in a way we know will help. But perhaps giving up the myth of a bipartisan crisis is a lesson we can take from recovery itself: The first step to solving a problem is admitting there is one.

There’s little reason to have faith that the current government in power will implement policies that will keep people alive. And there’s even less reason to wait. As unimaginable as it seems, the overdose crisis is going to get worse before it gets better. I can only hope that those who feel powerless over their addictions may realize that by working together, we have more power than we know.