When I woke last Friday to learn John McCain had voted to kill the “skinny repeal” bill, I literally breathed a huge sigh of relief—an enormous, almost desperate intake of air, as if I’d been underwater too long, and then a huge exhalation. I found myself repeating this through the morning—waves of relief, an emptying of the nearly bottomless well of fear that had built up over the last six months as the Republicans pursued their relentless effort to destroy Obamacare. Yet I can’t say I’m grateful to McCain. Yes, his vote was dramatic. But I would argue too much so, and cruelly so, for, as a recent New York Times story describes, this assault on the Affordable Care Act, of which McCain was such a vital part, took an enormous toll on millions of families with chronic or terminal health care problems.

Ours is one of them. And I suspect I’m not alone among those who were less interested in whether McCain would play hero than in whether we’d keep our health care.

I have a daughter with Type 1 diabetes. It’s a disease fatal if ignored, horribly destructive if mismanaged, quite manageable if you’re vigilant—but, in this country at least, enormously, ruinously expensive if you’re not well-insured. My daughter, who turned 13 this week, does a wonderful job of managing her diabetes and gets excellent care from a pediatric endocrinology clinic we visit four times a year. We can afford this only because the ACA expanded coverage, made our premiums manageable, and made her eligible for both Blue Cross and Medicaid coverage. If she has continued access to such coverage and care, she should live a long and healthy life. If the ACA were dismantled, she could face not only compromised care now but an adult life in which she might be denied coverage for her “pre-existing condition.” In the health care world envisioned by the GOP right wing, she could spend her entire life poor and without adequate care.

This is why we and others go through a hellish emotional roller coaster every time the GOP renews its attack. How many times did this cruel effort appear to die, only to be revived by Sen. Mitch McConnell and his cohort? How many times did they seem done, then rise to advance again? For our and millions of other families, it felt as if each night the zombies came back to claw at our doors and windows, howling for our children’s blood. It still doesn’t feel over.

I have another family member in this—my father’s brother, my namesake, Uncle David to me, Dave to his wife and parents and siblings, and to the U.S. Air Force, Maj. Thomas David Dobbs.

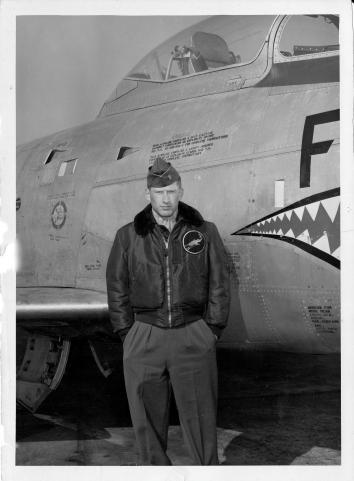

David, a third-generation Texan, was of McCain’s generation and a fighter pilot too—a hot dog, a superb flyer, and the best shot my father had ever seen. They hunted ducks together for decades; after their childhood, my father says he can’t recall ever seeing David miss. David joined the Air Force during the Korean War and was miffed that the war ended before he finished his training, because it denied him a chance to dogfight MIGs (a type of Soviet aircraft).

My uncle was politically conservative, and, like McCain, he flew in Vietnam. He piloted the perilous F-105 Thunderchiefs, known as Thuds because at low speed they so often crashed with a thud, and, more often, his favorite craft, the F-86D Sabre Dog. Like McCain, he was shot down. This happened in 1966. He was dive-bombing a military target when ground fire took out one of his elevator controls. When he yanked the stick to pull out of the dive, nothing happened. He was traveling at 400 miles per hour. The plane struck the earth seconds later.

His wingman, pulling out of his own dive, banked and looked back to see a ball of flame rising from where the plane had struck. He circled, looked, saw nothing good, and radioed to base that Dobbs had gone down and appeared to be killed in action.

Then the radio crackled and my uncle said, “The hell I’m dead. I’m on the ground alive and could use a lift.” He’d escaped after all. When he’d pulled on his stick and the plane didn’t respond, he didn’t do as many of us might have and pull back the stick again. Instead, in about the time it takes you to clap your hands twice, he released the stick and hit the eject button.

His problems weren’t over. The 400 mph air blast tore off his helmet, his watch, and one leg of his flight suit, slammed one of his arms against the back of the canopy, and snapped his head back something horrible. He landed in pain, stunned and disoriented. The fighters who had downed him were looking for him. But a chopper soon came, and, under fire and in a truly harrowing rescue, got him out of there and back to safety.

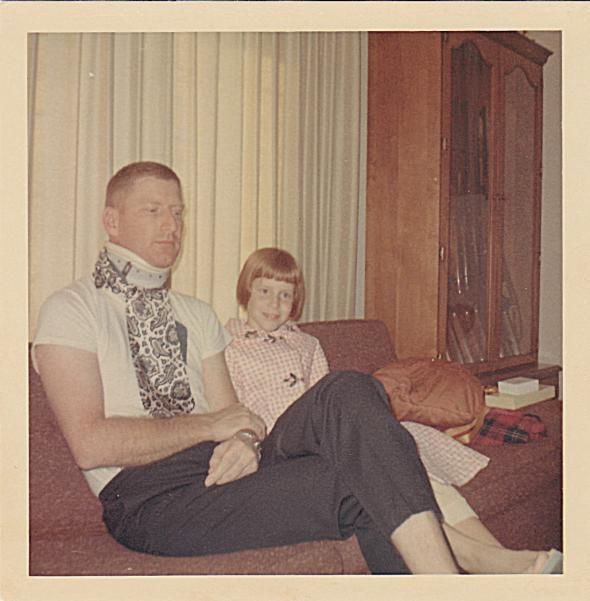

David was hospitalized for months with a broken arm, a punctured lung, leg injuries, and a bad neck injury. I’ve a photo of him taken once he got home. He’s sitting on a couch with one of my cousins, a tall redhead in a white T-shirt next to a redheaded schoolgirl delighted to have him home. He looks happy to be with her but not so happy with his neck brace; he wore it for almost a year.

Lou Turner Dobbs

Then he returned to flying—no combat, this time; instead he trained other pilots out in New Mexico. In 1969, escaping Houston’s heat to go to Colorado, my dad and mom and my siblings and I visited him and his family in Clovis and watched Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walk on the moon. David was back to his badass self by then, healthy, confident, kind but intimidating. He razzed my brother and me about our long hair. My siblings and I loved him. But he was a little scary.

Later in life he softened, becoming openly affectionate. I talked to him most Veterans Days. Before we hung up he’d tell me, “I love you. Stay out of trouble.” In 2004, when the U.S. was in the middle of the Iraq war, my older son, 13 then, interviewed David for a school oral history project. David was about 70 then. He seemed to remember everything. He talked about dodging the telephone-pole sized surface-to-air missiles the North Vietnamese would fire at him, slow but powerful (“One’s easy; three it gets complicated”), and told the story of being shot down. He talked about the base in Thailand, about one buddy who freaked out on his first combat flight, all those missiles fired at him, and was shipped back home.

And to my surprise, David, who used to say of Vietnam that we could have won the damn war if Johnson had let us, dammit, said that one of the things he learned from Vietnam was that a country should not fight a war unless it has broad support from the citizenry. He said this not as a political statement but as a statement of fact: You might think a war sensible or not; but if you didn’t have the support of the populace, you couldn’t and shouldn’t fight it effectively.

David died four years later, in October 2008, after a botched surgery at a civilian hospital. Surgeons went in to remove some cancerous tissue from his bladder and punctured it unawares, which created complications that kept him in the hospital long enough to get the MRSA infection that killed him. “This ‘old and bold pilot,’ ” as my father said in his email informing us that his beloved younger brother had died, “couldn’t dodge the missile this time.” One’s easy; three it gets complicated.

I don’t know what David would think about Obamacare or John McCain’s vote last week. But I suspect he’d have reservations with how McCain went about it. My uncle was neither a garrulous Texan type nor a silent type. He was what down there we called a straight talker, no games, no bullshit. He didn’t play coy. He said what he meant so you knew where he stood. So I reckon, as we’d say back home, that David might have thought McCain a bit of a showboat, and his melodrama last week—an entire choreography meant to let him dance the dance of a hero to the rescue—a bit over the top.

McCain, asked before the vote by reporters how he would vote—which way he was going to go on a bill that in one year’s time would leave 16 million more Americans uninsured, with no armor between themselves and ill health, and us with far less insurance than we had before—reportedly told them, “Watch the show.”

The most generous and naïve part of me wants to think McCain choreographed his show, rather than killing the debate on the ACA earlier in the week when he had the chance, because he felt that only by putting all the bills on the floor and killing them one at a time could the effort to destroy the ACA be finally put down. Unfortunately, that doesn’t fit with McCain’s stated position, which is that he wants the ACA taken apart, only through the supposedly honorable and gentle means that the Senate was supposedly once known for. Another, even more generous and naïve explanation, floated originally at Reddit, is that McCain was playing an ingenious long game to exploit a procedural rule that would let him put a dagger through the ACA once and for all. Unfortunately, this one doesn’t square with McCain’s explanation, his “yes’”vote on the Better Care Reconciliation Act bill or his clear opposition to the ACA. McCain didn’t orchestrate this drama show for the good of the country or out of regard for the sick and the threatened. He did it because he wanted to once again play a hero, and if possible a maverick as well, in a dramatic story.

If McCain wants another such role, I suggest he consider being a hero to the tens of millions who will be left naked, unprotected, and subject to the whims of disease and bad luck—prisoners of a sort—if the ACA is destroyed. He once fought to protect us. He could do so again.

I even have a script for him. It’s from the end of Witness. It’s the scene in which Harrison Ford, playing detective John Book, confronts his boss, Paul, a fellow cop gone bad who, after a gun battle in which two people have already died and a cover-up in which some other people died, now holds at gunpoint Ford and a dozen or so Amish farmers who’ve been sheltering him. Book, sick of it all and recognizing the long-awaited moment when moral advantage might be enough, asks his boss, “You going to kill me, Paul? And then what? You going to kill everyone? This man here, this child?” “It’s over!” Ford (as Book) finally yells. “Enough! Enough!”

McCain should prepare for this role. For McCain, like it or not, will almost certainly find himself playing some version of this scene when the GOP raises again the prospect of destroying the ACA. The only question is whether McCain will play the Ford character, who says, Enough!—or the cop who doesn’t realize it’s time to stop.