Illness is not something most healthy people think about regularly. And they shouldn’t. Although as a physician I want to help my patients make smart choices to preserve their healthy state, I also don’t want to deny them the blissful innocence that comes with taking good health for granted.

However, just as the disability community coined the term “temporarily able” to refer to those without disabilities, the reality is that those of us who are healthy are only “temporarily healthy.”

A random encounter with an unprotected partner or a nasty stomach bug or the Second Avenue bus could bring anyone at any age into contact with the health care system. Just getting older and acquiring hypertension or arthritis can do it. And then suddenly you learn. You learn what your insurance does or does not cover. Or you learn what it means to get sick without insurance. You learn that you are not invincible.

For Americans who are still temporarily healthy, the politics of health care can feel distant. The details of the House and Senate’s health care bills can feel arcane and overly partisan. But we all have skin in the game. (And even if it isn’t your own skin, consider your parents and grandparents, nieces and nephews, children and siblings.)

Like most physicians, I keep my personal life and political views steadfastly out of the exam room. But as I watched the news about health care ratchet up over these last few weeks, I stopped seeing the partisan tit-for-tat. Instead, I started seeing my patients.

I saw S, who is only in his 30s but has diabetes. The one time that his insulin prescription ran out, he nearly ended up in the ICU. What will happen to him, I asked myself, if he is one of the 22 million Americans who will lose coverage if the Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act is passed?

I saw E, who is 26 and has an autoimmune disease. She juggles her medical appointments while holding down her job at a restaurant and taking classes at a community college. What if she draws the short straw when Medicaid gets cut?

I saw R, who is in her first year of college and gets her birth control from Planned Parenthood. What if there’s no Planned Parenthood? What happens if she gets pregnant?

I saw my waiting room full of my older patients who have emphysema, cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease. What happens if there’s a disruption in their medical care? For many of them, there’s not a squeak of wiggle room. Loss of medical care could easily equal loss of life.

If this plan for health care is passed, it could gravely harm my patients—and all patients. If 22 million Americans lose health insurance, it’s estimated that there could be about 20,000 additional deaths per year. If I came across signs of an epidemic like Legionnaires’ disease or a medication with a toxic side effect that needs to be recalled, my duties as a physician would compel me to speak up. It dawned on me that this law is no different. It’s a medical threat, and therefore, as I doctor, I have to speak up.

So I wrote an op-ed for the New York Times encouraging nurses, doctors, and other medical professionals to speak up against it. The funny thing about op-eds is that you, the author, don’t get to choose the title—the editors do. So I was just as surprised as anyone else when I opened the newspaper and saw the title, “Time for a Doctors’ March on Washington.”*

My inbox burst open with letters asking, “So when’s the march?” Doctors and nurses, it turned out, were more than ready to put their boots on, and plenty of their patients were urging them on. There wasn’t enough time to create an actual march (like so many other things about this bill, the timing of the vote has been a bit of a mystery). So we settled on a virtual march on Washington. Along with filmmaker Catherine Stratton and a few of her colleagues from the Resistance Media Collective, we pulled together the HouseCalls Campaign over the course of three hectic days.

House calls are a medical tradition dating back hundreds of years. When a patient is truly in need, a doctor or a nurse puts her boots on and gets out there. Right now, the collective patients of America—that would be all of us!—are in need. There is real medical threat and it warrants a serious medical response. HouseCalls Campaign is encouraging doctors and nurses to call key senators to tell them how this bill will affect their patients.

When I call these senators, I tell them about my sick and fragile patients who might die if they lose their coverage. I also tell them about my young and healthy patients who will have less time to be healthy if they lose access to care. I tell them about my healthy patients who might never have that discussion with a doctor that uncovers a genetic disease in their family history. I tell them about my healthy patients who might never get that conversation with a nurse during a routine vaccination that uncovers depression or addiction.

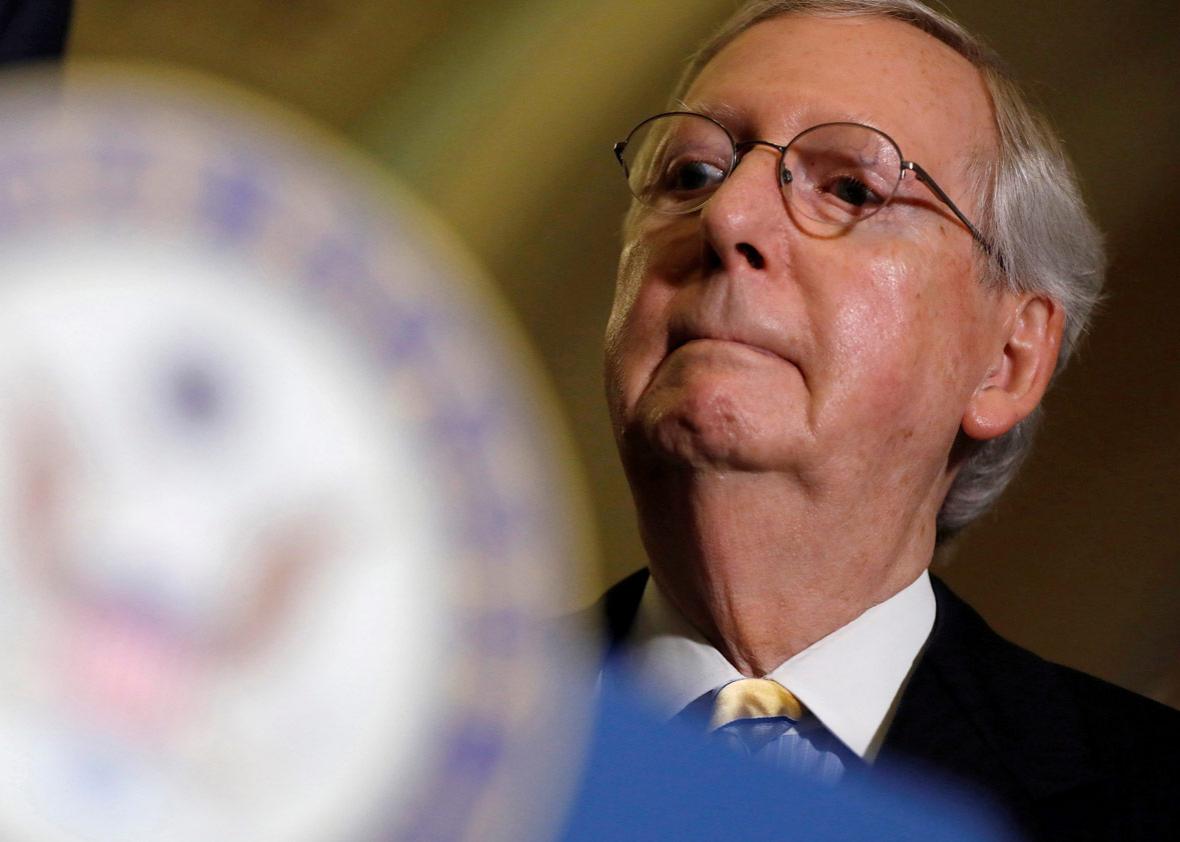

I’ve found that most Senate offices are receptive to our calls. One staffer said, “Wow, it’s really great to hear from someone who’s actually in health care.” Even when I call senators who are not from my state, I get a respectful hearing. I explain that I’m not in their district, but that my patients will nevertheless be affected by the senator’s vote. I tell them that as a physician, I took an oath to “do no harm,” and so I have to speak up if I think my patients will be harmed. Even Mitch McConnell’s and Paul Ryan’s staffers don’t have an easy comeback for that one.

Most senators have only a passing knowledge of what actually transpires when people make medical decisions. It is the people in the clinical trenches—nurses, doctors, physician assistants, med students—who know. These are the people who understand what happens when patients lose access to medical care. These are the people who will care for those 20,000 ill-fated patients—not in primary care clinics but in emergency rooms, ICUs, and morgues.

Medical professionals are uniquely qualified to advise the Senate about the side effects of its proposed legislation. Since the Senate isn’t having any public hearings in which we might offer our professional advice, the millions of American health care professionals will simply have to make HouseCalls to them. Because in a medical emergency, we have to do whatever it takes. Our patients are counting on us.

*Correction, July 6, 2017: This article originally misstated when an op-ed by the author was published in the New York Times. (Return.)