As currently written, the American Health Care Act allows states to opt out of the popular Obamacare provision that bans insurers from discriminating against people with pre-existing conditions. Twenty-seven percent of adult Americans under the age of 65 have a declinable pre-existing condition, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, and if the AHCA becomes law, any number of them could become uninsured. The guiding GOP arithmetic takes as a given that people should pre-emptively pony up for conditions beyond their control—including, yes, having a second X chromosome. Millions more have conditions—from asthma to the ever-inconvenient urinary tract infection—that could also jack up the rate of coverage, making insurance prohibitively expensive.

What their calculations don’t yet consider are the could-be conditions embedded in our DNA. Our genomes provide a window into scores of genetic risk factors that have yet to present as full-fledged pre-existing conditions. If the GOP insists that people can be charged differently depending on their current health, what’s to say they’ll stop short of asserting that we could be charged according to our genomes?

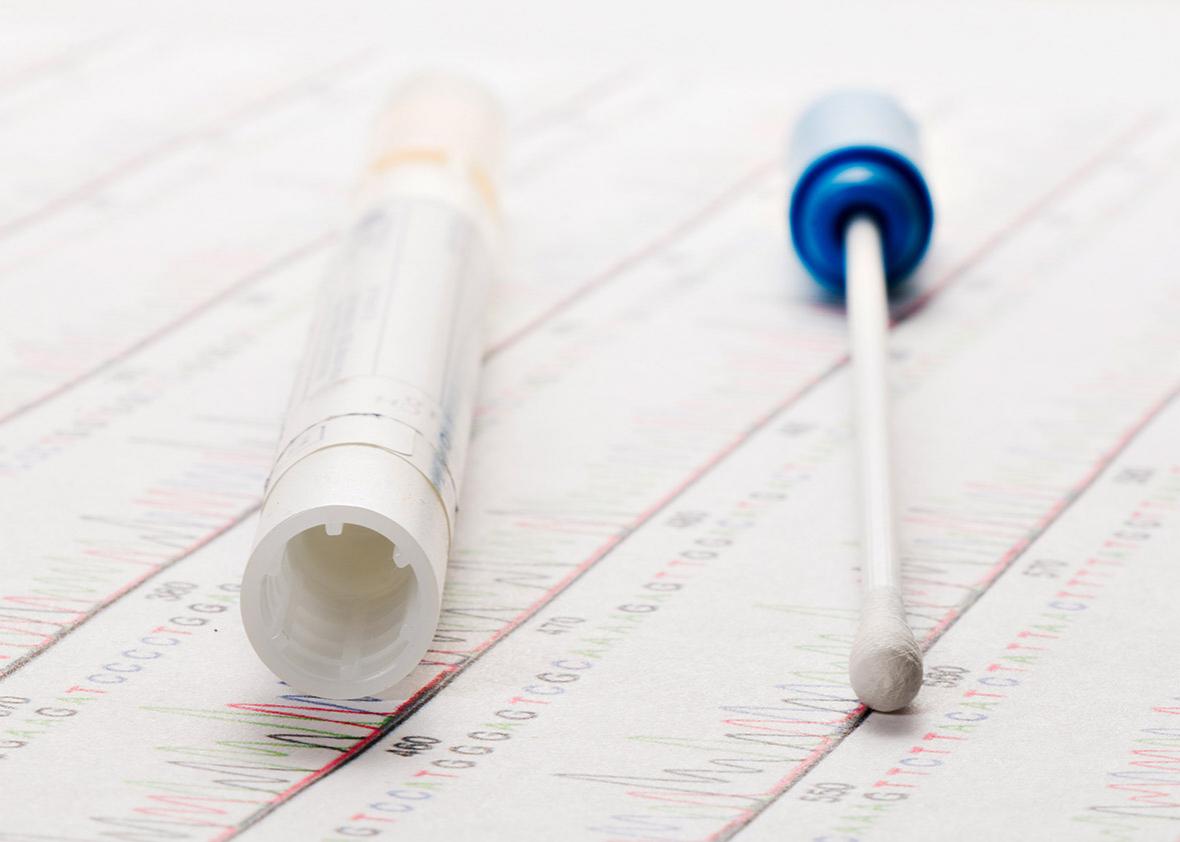

The personal genetics revolution is well-underway. More Americans than ever have access to the information contained in their genetic material. When the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, the cost of sequencing the 3 billion As, Cs, Gs, and Ts that comprise the human genome rang in at $50,000. Today, that price tag has plummeted to $1,000 with promises of a $100 genome in the near future. Already a mere $99 and a dab of spittle will give consumers a good sense of their genetic risk factors from private genetic testing company 23andMe. Last month, the company received Food and Drug Administration approval to test for predispositions to 10 medical conditions. And even before that came through, customers could upload the raw DNA data generated by 23andMe into “interpretation only” services like Promethease for a DIY disease risk assessment.

And that’s just personal use of genetic information—the current $1,000 price tag means its already accessible in many medical settings. The question now turns to how the data deluge brought on by the genomics age will be used. Personal genetics can empower patients, doctors, and researchers to make more informed decisions around health care. But while this information could help us make better medical choices, it could also be used to fine-tune insurance algorithms, calculating premiums on a sliding scale of genetic risk.

Americans saw this trade-off coming. The Human Genome Project spurred concerns around genetic discrimination in the 1990s. Over a decade before Obamacare’s pre-existing conditions protections, patient and civil rights organizations came together to press for protections against genetic discrimination. Thirteen years of advocacy efforts led to the bipartisan passage of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008. GINA prohibits employers and health insurers from using genetics to influence hiring decisions and insurance coverage.

The legislation was celebrated as the “first major civil-rights bill of the century.” It eased concerns around genetic discrimination to ultimately encourage people to take advantage of emerging genetic technologies and therapies. GINA’s protections helped advance genome research, and today millions of Americans have submitted genetic samples for testing. A government-funded $215 million Precision Medicine Initiative is now underway with the goal of collecting genetic and health data from over 1 million Americans to better inform biomedical research.

That means millions of genotypes that can be used by clinicians and researchers to home in on and characterize genes linked to specific diseases. That also means millions of genotypes that could be factored into the underwriting calculus that prioritizes profits over patients.

Life, disability, and long-term care insurance, which are not covered under GINA’s provisions, already use genetic testing results to deny coverage to otherwise healthy individuals. And when it comes to health insurance, GINA isn’t perfect. The legislation only protects people who are genetically predisposed to a disease if they are asymptomatic. Once a person begins showing symptoms, GINA no longer matters. But for a while, Obamacare closed that loophole. When it was enacted, personal genetics was still in its infancy—23andMe had less than 50,000 customers at a price tag of $999, and AncestryDNA had yet to launch. So in the years since the ACA’s passage, shoring up protections against genetic discrimination has received little legislative attention.

Obamacare repeal reopens the gray area between genetic predisposition and a pre-existing condition. The AHCA’s MacArthur amendment would require that states opting out of Obamacare’s pre-existing conditions rule set up high-risk pools for sick people who incur higher medical costs. But what “sick” actually means is increasingly up for debate. Does a BRCA1 mutation, which portends a 55 percent to 65 percent risk of developing breast cancer by the age of 70, count as a pre-existing condition when you’re 30? When you’re 60?

DNA doesn’t encode certain destiny: Carrying the BRCA1 mutation offers no more clarity than the percentage given above. But without the ACA, GINA is the only thing stopping insurance companies from practicing genetic determinism when they decide what conditions warrant higher premiums or coverage denial. Republicans, who control every branch of government, have shown that they believe different people should be required to pay different amounts on the basis of what essentially amounts to dumb luck. And we already know they have little interest in regulating corporate interests. Besides, “nobody dies because they don’t have access to health care,” remember?

Even with GINA and Obamacare protections still in place, Americans remain wary of participating in whole-genome sequencing studies, citing fears of discrimination from life insurance companies. Their skepticism is warranted: For all its attributes, the ACA paradoxically opened a GINA loophole by encouraging employer health care plans to offer discounts for participating in workplace wellness programs. GOP lawmakers recently seized on this idea, introducing legislation to compel employees to share genetic test results with their employers.

We already know the current government is not much interested in science—but if that science involves calculating maximizing profit margins at the expense of patient empowerment, they just might perk up.