The Federal Trade Commission just cracked down on an unusual product that has long enjoyed exemption from regulation: homeopathic drugs. Available everywhere from Whole Foods to CVS, homeopathic products are advertised as an effective way to treat a wide range of conditions. Just the “H” section of CVS’ online homeopathic medicine webpage mentions hay fever, head injury, hemorrhoids, high blood pressure, HIV support, and hypertension. According to 2007 government data, Americans spend over $3 billion a year on homeopathy, and the market appears to be growing steadily.

Despite their popularity companies selling these products have never been required to show they are effective at doing what they claim. So yesterday, when the FTC announced its “enforcement policy statement” about homeopathic product labeling, it was a welcome move. Unfortunately, the recommendations are pretty minimal: After soliciting comments, commissioning studies, and convening a one-day public workshop, the agency produced a 24 page report that concluded customers were likely to be deceived by labels that did not carry the appropriate disclaimers, and therefore disclaimers stating that these products are untested will now be required. The requirement is not technically a law like, say, the Food and Drug Administration regulations that govern prescription drug labels. Instead, A. Wes Siegner, an attorney who specializes in FTC and FDA regulation, told me “it’s an official heads up that if you want to avoid litigation you need to play by the rules.”

The rules require packaging to effectively communicate two key disclaimers:

- “There is no scientific evidence that the product works.”

- “The product’s claims are based only on theories of homeopathy from the 1700s that are not accepted by most modern medical experts.”

That, to this day, a health care product deemed by the FTC to have “no scientific evidence” has avoided substantive regulation is due entirely to the peculiar nature of homeopathy. Developed in the late 18th century by a German physician named Samuel Hahnemann, the novel approach to healing blended scientific, religious, and downright strange concepts, like so from Hahnemann’s book The Organon of the Healing Art: “It is only by means of the spiritual influence of a morbific agent, that our spiritual vital power can be diseased; and in like manner, only by the spiritual (dynamic) operation of medicine, that health can be restored.”

There is near-unanimous mainstream scientific consensus that homeopathy’s purported mechanism of action—using ultra-highly diluted substances to allow “like to cure like”—runs counter to basic principles of chemistry, biology, and physics. As health policy expert Timothy Caulfield recently said, “to believe homeopathy works … is to believe in magic.” Detractors like him suggest the most likely explanation for homeopathy’s perceived efficacy is a combination of wishful thinking and placebo effect. This view of homeopathy has been popular for nearly two centuries: “The homeopathic method,” wrote physician Jacob Bigelow in 1835, “consists in leaving the case to nature, while the patient is amused with nominal and nugatory remedies.”

Nevertheless, practitioners and patients alike have successfully championed homeopathy into the present day. Unmoored as it is from the rest of conventional scientific thinking, regulators have had no idea how to classify homeopathic products. Most products are engineered to contain only infinitesimally small amounts of the active substance, which means they are almost always harmless. Consequently, until now, the FDA and the FTC found it easier to take a hands-off approach, which means that homeopathic medicine packaging has been basically governed by practitioner-authored guidelines and the FTC’s general injunction to be truthful and not deceptive.

That the FTC decided to regulate homeopathic medicine may seem like a step in the right direction. But the mandate they’ve come up with—to require disclaimers on these products—is nearly as lacking in scientific evidence as the products themselves. Requiring disclosures will probably do nothing to help people realize the true nature of what they’re buying.

Time and time again, studies have shown that with few exceptions, “This claim has not been approved by the FDA”–style disclaimers do little to inform consumers or change their purchasing habits. As I reported for Slate in 2014, the FDA’s own studies show this, with most disclaimers making no difference and some actually making heath claims appear persuasive! The FTC’s more recent studies on homeopathic medicine disclaimers are not encouraging, with 25-45 percent of consumers reporting that homeopathic products are FDA approved—after looking at a package with a disclaimer that says they aren’t.

The problem is bigger than inadequate packaging disclaimers. “I’m not confident that a disclaimer could ever effectively communicate ‘there’s really no evidence this product works,’ ” said Georgetown Law professor Rebecca Tushnet.* “Many consumers expect ‘they couldn’t say it if it wasn’t true’ and disclaimers are probably not good enough to combat a belief that basic.”

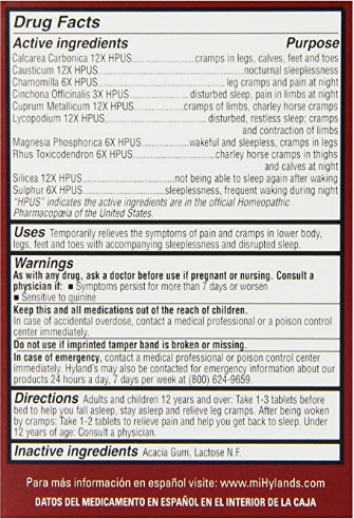

Screenshot via Amazon

Homeopathy compounds the problem. (That’s a homeopathy pun.) The labels on these drugs look incredibly scientific. They’ve got weird units (12X HPUS), and technical-sounding ingredients (Cuprum Metallicum), and even name-drop “the official Homeopathic Pharmacopeia of the United States.” The whole thing evokes a standardized, highly refined system, and for reasonable people unfamiliar with homeopathy it’s understandably hard to believe that products based on such a system that make health claims and are sold in CVS could actually be nothing more than placebos.

What’s worse, the second point required by the FTC’s new labeling standards may reinforce some consumers’ beliefs in the efficacy of the product. Prior beliefs and confirmation bias have a strong effect on how we process information. Those drawn to homeopathic medicine are more likely to be skeptical of mainstream medicine, a preference that homeopathic advertising plays to with its emphasis on descriptors like “natural.” To read that most modern medical experts don’t accept homeopathy highlights the anti-establishment allure of the product. Similarly, the appeal to antiquity means that mentioning homeopathy’s ancient origin will actually serve to bolster its plausibility. After all, goes the fallacious thinking, if it weren’t true and didn’t work how could it have stuck around for over two centuries?

This is not to rail on the FTC, which should be applauded for its strongly worded and scientifically accurate statement, especially given how difficult it is to mandate disclaimers without violating consumers’ rights. It did the best it could given the limitations it faces. But we cannot, as a society, let such statements breed complacency when it comes to addressing the problem of pseudoscience and deceptive marketing. In truth, what’s necessary is recognition that our education system is badly misallocating resources and leaving us susceptible to such claims. We learn a great number of scientific facts in middle school and high school, but spend virtually no time on the philosophy of science. This is a shame. Without understanding the process by which our culture decides on what counts as scientific knowledge, people are left to judge the reliability of a claim with little more than “Was it made by someone with letters after their name?” and “Does it sound like the science I did in school?”

When these questions are the only tools in the public’s epistemic toolkit, the gates are open to all sorts of pseudoscientific nonsense, from quantum healing to a lot of what has passed as macroeconomics. Confronted with an epidemic of inadequate education, I can see how it would be tempting to administer it on packages in an ultra-highly diluted form. Doing so, combined with anecdotal evidence of success, might even make us feel better about the problem. But that feeling isn’t based on actual improvement. It’s just wishful thinking and the placebo effect. And while placebos are often useful, in certain cases they can be dangerous, allowing the patient to ignore an illness until it’s gone too far. We wouldn’t want that to happen to someone taking homeopathic remedies for a serious disease. Let’s not let it happen with disclaimers and public scientific literacy.

*Correction, Nov. 16, 2016: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article misspelled Rebecca Tushnet’s last name. (Return.)