Here’s how I usually start a conversation with a patient about birth control:

None of the methods I have for you today are perfect. We don’t have perfect, though I wish we did. We have pretty good; we have good enough; we have not-great. And then we have the roll-the-dice method.

All of these—including rolling the dice—have side effects.

This inevitably results in a ton of questions, on everything from efficacy and side effects to cost and convenience. That’s to be expected.

Recently, there has been some new research, and therefore, news coverage, of the idea that birth control can increase your risk of depression—including this new paper by Skovlund et al. And so women who have spent some time Googling before an appointment come prepared. What about depression? What about emotional health?

These are understandable concerns. Emotional health is important. Depression is important. If you tell me you don’t feel good on a pill or another medicine, I will try to help you figure it out. And it does demand figuring out, because it’s hard for any of us to know exactly why we’re not feeling great—lives are complicated and often contraception is not the only thing that’s changed. But if you think it’s the pill, I’ll listen to you, because maybe it is. Hormones are strange, idiosyncratic substances; we don’t know nearly enough about them, and they affect people differently. I’ll listen to you; I’ll even go so far as to say that any health care provider should listen to you.

But the study by Skovlund et al. shouldn’t be the reason why.

For one thing, this particular study is flawed, because its design is flawed. This kind of research performs epidemiologic work by using a database that was designed for administrative purposes, which is a terrible idea, says David Grimes, a clinical professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and a longtime critic of studies of this type. “You can’t do good epidemiologic studies from databases like this.” He compares it to using the Department of Motor Vehicles’ database of people’s height and eye color to figure out why people get into car accidents. You may, through the magic of statistics, manage to cobble together a conclusion that has beautiful numbers, but is that conclusion related to reality? Will that conclusion help you lower the car accident rate? Not likely.

This particular Danish database, in fact, has been used frequently and is the subject of multiple well-researched editorials pointing out its flaws. For example, here. Or here. Or the full paragraph devoted to it in this other study, here. Like many huge databases, this Danish one is catnip for researchers, granting scientists immense numbers of patients and gorgeous statistics and p-values with very little added cost. But, says Grimes, “If you want to do a proper study, you have to put the money and effort into it. You get what you pay for in research.”

We love using big data and algorithms for our criminal justice system, and election polling, and in our school assessments. We love it because we can put cartloads and boatloads and airplane loads of data into a computer, and get what we think is an answer. But the data that was put into this database was not collected by clinicians or for clinical purposes; it was collected by administrators for administrative purposes. And like any other information, the amount of data is not nearly as important as the relevance of the data. It’s the quality, not just the quantity.

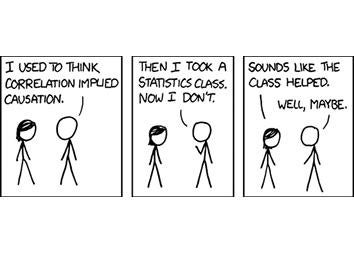

This study showed an association between birth control and depression. Specifically, both women who took oral contraceptives (which go through the bloodstream and to the whole body) and women who had progesterone IUDs (such as the Skyla or Mirena, which concentrate hormones in the uterus) seemed to have higher rates of depression. But like all epidemiologic studies, it can only prove that there is some correlation between hormones and depression (and only in this particular data set), not that one causes the other.

Xkcd

(Did I write this whole piece just to use one of my favorite cartoons ever? Perhaps.)

We also know that the progesterone IUDs produce hormone levels that are lower—like, 90 percent lower—than those produced by oral contraceptive pills. So that’s a biologic implausibility of this study: It doesn’t make a ton of sense that such different exposure would be related to as much depression risk as full-body exposure that’s produced by pills, even though that’s what the data suggested.

And after all that, we still want to know: What’s the story with depression and hormonal birth control? The answer is that we still don’t know much more than we did before this flawed study came out. That doesn’t mean contraceptive side effects, including (perhaps especially!) mental health illnesses, should be glossed over. On an individual basis, if you’re using one of the “pretty good” forms of contraception and you get depression or other serious side effects, then it turns out that that specific method birth control is no longer “pretty good” for you. So if that happens, we’ll explore other options.

But in terms of general practice guidance for larger populations, there really hasn’t been enough research out there to assess the connection between contraception and mental health issues. The relationship is likely complicated—for example, contraceptives are often successfully utilized to treat depression related to premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

If so many of our methods of birth control were found to be reliably related to an increase in depression, we would need something better, and something fast. But that’s not where we’re at yet. We should keep researching the side effects of birth control, but we shouldn’t abandon it.

The larger truth—one that cannot be reflected in a large database study—is that for most women, contraception isn’t a luxury or a privilege. It’s a necessity. It is the key with which many women unlock lives of equality, of economic parity, of freedom. The rolling-the-dice method, it turns out, isn’t risk-free (but you know that already). It comes with concerns too, not least of which is unintended pregnancy, which itself comes with (wait for it) a pretty impressive risk for depression (among many other complications).

The absence of contraception is not an acceptable state for most women. Women and their doctors have fought for a long time to make access possible, to inform patients of the risks as well as the benefits, and to work toward a health system where prevention of pregnancy is seen as a legitimate use of health care dollars. Those women and those health care dollars deserve accurate information about the risks of these medications, which allows them to decide which contraception to opt for. But women deserve great studies, which honestly delineate those risks, using databases designed for this purpose.

For birth control, I have pretty good; I have good enough. I think that as a society, we can—and should—one day find a “perfect.” But until we do, let’s not dismiss many of the options we do have based on a flawed study.