This story is reproduced with permission from The Conversation.

Acetaminophen has been around for more than 50 years. It’s safe and many guidelines recommend it as the go-to treatment. At least, that’s the conventional view of the drug. It’s a view so ingrained that it’s rarely questioned. The trouble is that the conventional view is probably wrong.

Huge amounts of acetaminophen are used to treat pain, measured not in how many tablets are used but in the thousands of tons. For the U.K., an estimate of the amount of acetaminophen sold is just less than 6,300 tons a year. That’s 35 tons per million of population: 35 grams or 70 acetaminophen tablets each, every year.

But does it work? The evidence is that it probably does not work at all for chronic pain. Large, good, and independent clinical trials and reviews from the Cochrane Library show acetaminophen to be no better than placebo for chronic back pain or arthritis. This is at the maximum daily dose in trials lasting for three months, so it has been pretty thoroughly tested.

Acute pains are sudden in onset and go away after a while (headache or pain after an operation, for instance). For these, reviews from the Cochrane Library show that acetaminophen can provide pain relief, but only for a small number of people. For postoperative pain, perhaps 1 in 4 people benefit; for headache perhaps 1 in 10. This evidence comes from systematic reviews, often of large numbers of good clinical trials.

These are robust and trustworthy results. If acetaminophen works for you, that’s great. But for most, it won’t.

Is it safe? Safety boils down to examining really bad things happening to a very small number of people who take a drug. Unless the rate of the very bad thing is vanishingly small, the authorities won’t let us buy the drug from a petrol station. If we want to study those rare events, then we need study large numbers of people. Partly because acetaminophen is such an old drug, these studies have largely not been done until recently.

Those we have tell us that acetaminophen use is associated with increased rates of death, heart attack, stomach bleeding, and kidney failure. Acetaminophen is known to cause liver failure in overdose, but it also causes liver failure in people taking standard doses for pain relief. The risk is only about one in a million, but it is a risk. All these different risks stack up.

There are some scary facts about how much we, as ordinary members of the public, know about painkillers. Here are a few.

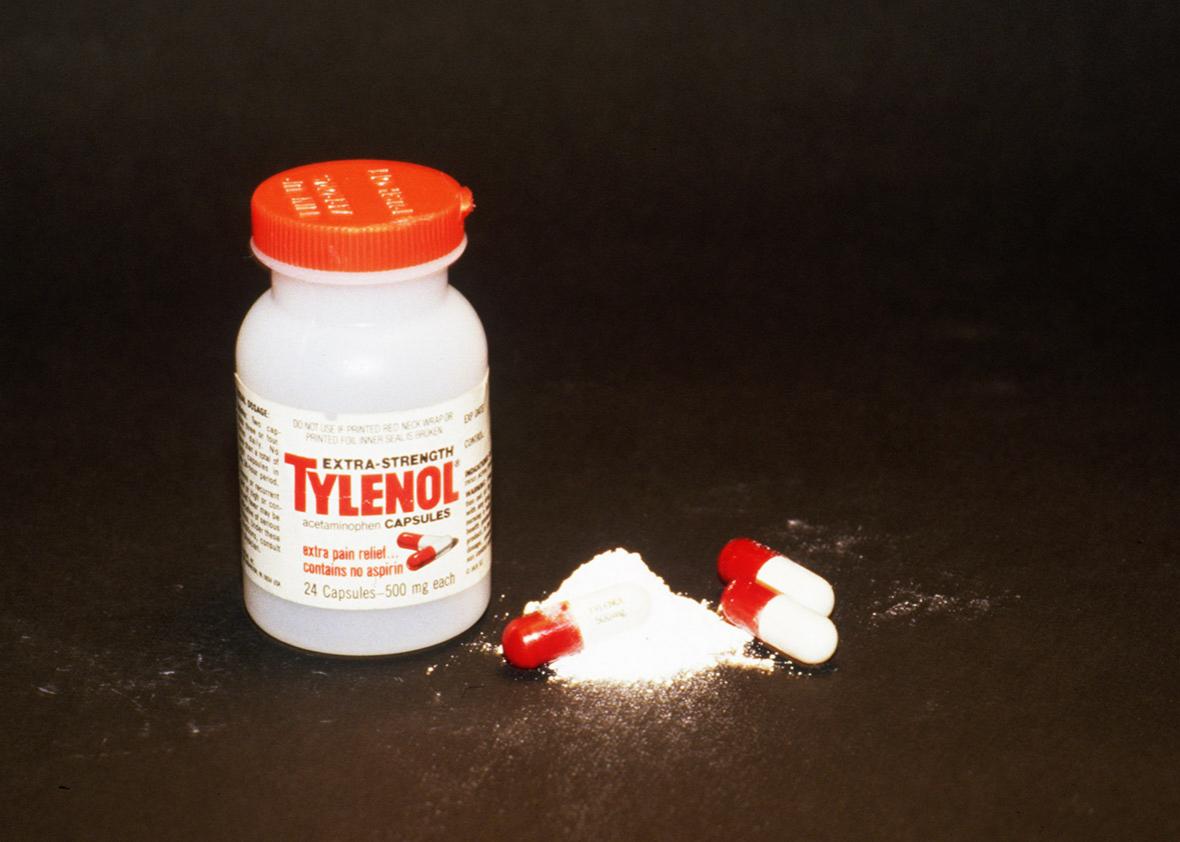

Many people don’t know what is in their pain relievers. A study in a London emergency department found that half of the patients thought ibuprofen contained acetaminophen. In the U.S., half of a similar group did not know that the popular brand of acetaminophen, Tylenol, actually contained acetaminophen.

Most people have no idea of the maximum daily dose of acetaminophen. In the UK about 1 in 4 people frequently exceed the maximum daily dose. (It’s 4,000 mg, or eight tablets, by the way.) In the U.S., half did not know the maximum daily dose, and 1 in 20 thought it as high as 10,000 mg.

Acetaminophen is not just in acetaminophen, but all sorts of cold and flu medicines as well, and headache tablets. Around 200 million packs of paracetamol are sold without prescription in the U.K. every year, though sales fell after pack-size restriction. In the U.S. it could be 1 billion (but different pack sizes and tablet doses).

The conundrum is what to do with this information for a drug that has a limited effect but is dangerous in overdose. It’s a headache for regulators and licensing authorities, not to mention organizations trying to help doctors make sensible treatment decisions. Nor is there a simple alternative. Nonpharmacological methods of treating pain are largely without good evidence. Other drugs may work better, but they have side effects too.

Let’s not rush to judgement here and dismiss acetaminophen entirely. But a rethink is surely timely.