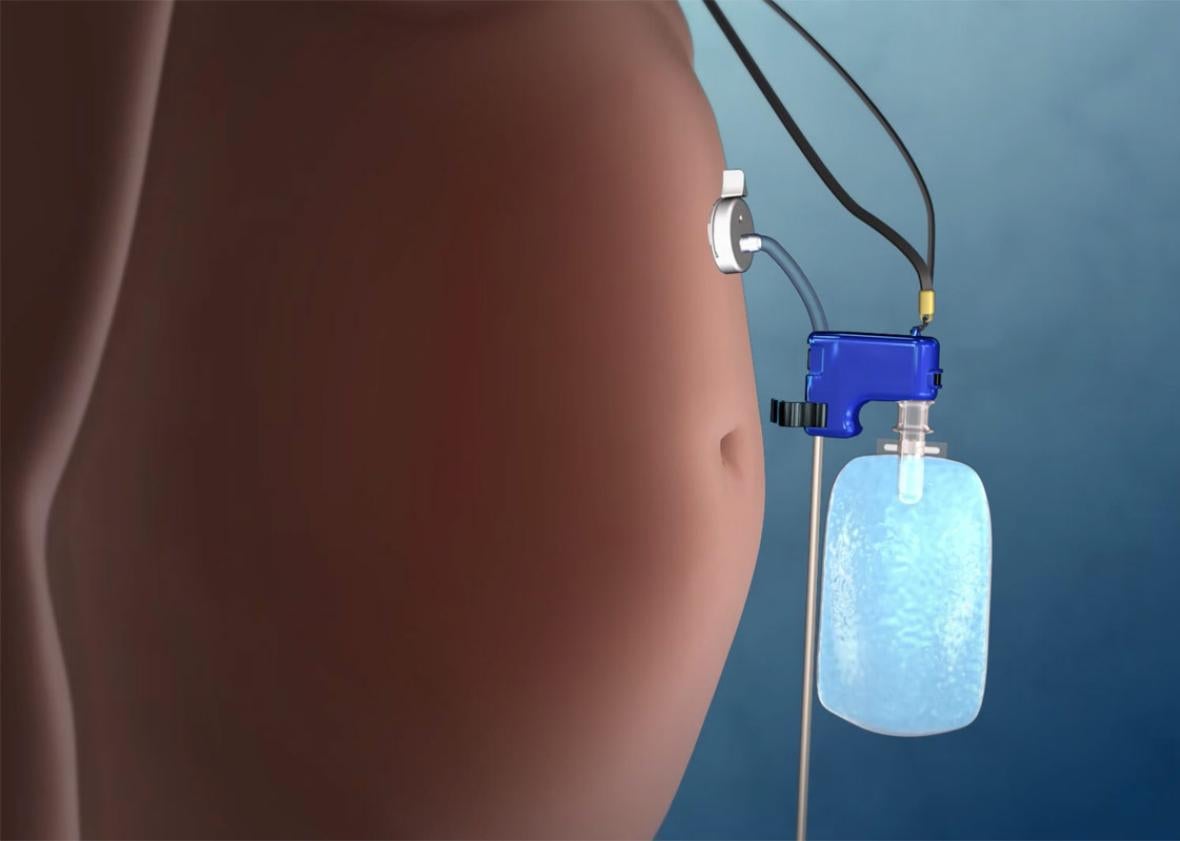

In an attempt to gain new ground in the battle against obesity, the Food and Drug Administration recently approved a device, called the AspireAssist, that enables users to empty the contents of their stomach via a surgical-inserted tube following consumption of a meal. Dean Kamen, inventor of the Segway, came up with the idea for the device and developed it with the help of physicians that specialize in the treatment of obesity. About 20 to 40 minutes after eating, users just pop to the bathroom, connect a longer tube to a hole in their body that is directly connected to their stomach, and drain 30 percent of their consumed food right into the toilet.

It’s clear how the device might lend itself well to reflexive disgust. Online media outlets coined the term “medical bulimia” to describe the immediately apparent similarities with the eating disorder bulimia nervosa—compulsive eating and purging. “Is this new device simply a condemnable medical bulimia machine?” read the first line of one story. Another concluded “this terrifying invention is also, let’s face it, an automatic bulimia machine.” But to dismiss this device as “medical bulimia” shows both a misunderstanding of the eating disorder and also vastly overestimates how easy it is for those with morbid obesity to lose weight.

Sure, the device sounds like an easy way to toss your food after eating it. But to draw comparisons to bulimia demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of bulimia, which is a psychiatric disorder. “There is no such thing as ‘medical bulimia,’ ” says Dr. Anastassia Amaro, medical director of Penn Metabolic Medicine, who oversaw AspireAssist’s clinical trials there (she received no financial compensation from the manufacturer). “Bulimia [nervosa] is a psychiatric diagnosis that has specific traits, including forceful vomiting and feelings of guilt and shame.”

The FDA does require doctors to screen for a history of eating disorders before inserting the device, to ensure anyone with the mental predisposition for the disorder is not enabled by the device. But the device hardly allows bulimic tendencies: It’s impossible to completely empty your stomach using it. (The exact placement of the tube, near the top of the stomach, also means very little stomach acid will ever be removed, circumventing many of the detrimental effects of bulimia.)

When considering the scope of our obesity crisis, it seems at least worthwhile to pursue all options that help people lose weight, and the results so far are promising. For those with severe to morbid obesity, defined as a body mass index, or BMI, between 35 and 55, the device promises to reduce calorie intake by up to 30 percent. Early clinical trials have shown that patients who received both the device and lifestyle counseling lost more than 12 percent of their body mass on average in one year, compared with 3.5 percent in patients that received lifestyle counseling alone. For a 6-foot-tall man weighing 300 pounds, that’s the difference between losing 36 pounds and losing just 10—a 5-point downgrade in BMI.

For many struggling with obesity, dropping pounds is the best way to resolve weight-related health issues like diabetes and high blood pressure, but it’s extremely hard to do. According to the Boston Medical Center, 45 million Americans attempt to diet each year, and researchers estimate that within five years, 41 percent of that population—a full 18 million people—will have gained at least as much weight as they lost. When it comes to technical solutions, the most effective means we have so far is gastric bypass surgery. Patients who undergo that procedure typically lose 70 percent of their excess body weight within the first 12 months. In our theoretical 300-pound man, that’s more than 70 pounds, almost twice as effective as AspireAssist.

In the U.S., though, gastric bypass surgeries can cost up to $57,000, and because the surgery amounts to a dramatic replumbing of the intestinal tract, it’s also risky. It requires full anesthesia and a three-week recovery period, and 1 in 200 people who undergo the surgery die due to complications. In comparison, AspireAssist is much less dangerous to insert. It takes just 15 minutes in a doctor’s office. As an outpatient procedure, it’s cheaper, and also relatively noninvasive—you won’t even be knocked out to get it inserted. Compare that experience with that of surgery, and you can see why the device has been approved in Europe for five years already.

One concern is that people could use the device in a way that causes them to lose weight without changing their behavior. That’s possible, but by design, some components of the device degrade after six weeks and must be replaced, so the individual has to check with a doctor at least eight times per year—a perfect interval for lifestyle and behavioral counseling.

Another factor that might cause some potentially inadvertent behavior change is users must consumer more fluids and chew more carefully—otherwise food might get stuck in the tube. But these are also healthy changes that can aid with digestion and ultimately promote weight loss. Perhaps as a result of this more deliberate eating, at the end of the study, many participants had actually demonstrated a decrease in their average portion size.

Sure, the idea of AspireAssist is sort of extreme. But at the same time, so is the obesity epidemic. Some solutions work for some people; others work for others. At the very least, we should be willing to consider any evidence-based method for assisting in what is a very medically difficult endeavor. Even if they make us feel a little squeamish.