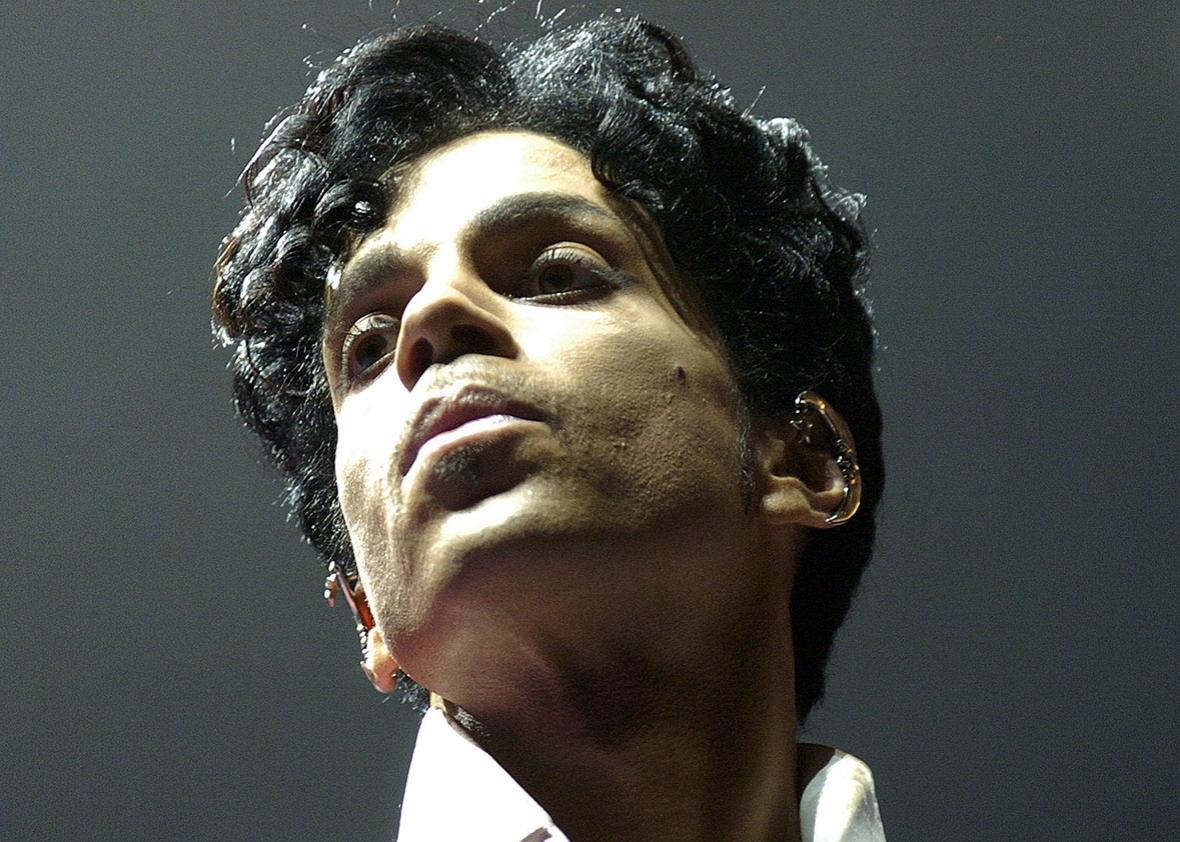

Days before his death on April 21, associates of Prince contacted Dr. Howard Kornfeld, a California-based addiction treatment specialist, reportedly over concerns that the musician had developed an opioid addiction. Prince never had a chance to consult with Kornfeld; on June 2, the Midwest Medical Examiner’s Office reported that his death resulted from the self-administration of a drug called fentanyl. We have limited information about the circumstances surrounding Prince’s passing—we know the drug that killed him, and we know that he was suffering from chronic pain in his hips and knees. Even so, it’s possible to piece together what kind of therapy would have been provided to him, as well as the best course of treatment for millions of others who, as Prince did, struggle with chronic pain and opioid dependency.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid used around the world for the management of severe pain, in battlefield medicine, and in anesthesiology. In addition to its pain-relieving properties, it can also induce a state of relaxation, tranquility, and euphoria. In recent years, the drug has also found its way into the illicit market. (We don’t know if Prince got his fentanyl legally or illegally.) Fentanyl is 40 to 50 times more potent than heroin and 80 to 100 times more potent than morphine. This doesn’t mean that fentanyl is fundamentally different from heroin or morphine—all of these drugs act on the same opiate receptors in the brain. But its heightened potency does increase the risk of respiratory depression and overdose. And its potency also makes fentanyl an appealing option for drug dealers since it can be smuggled in far smaller quantities than other drugs. It’s readily synthesized by the Mexican drug cartels and, in the U.S., is increasingly found combined with heroin. If I was a drug dealer with fentanyl to sell, I might mention that among American anesthesiologists who become opiate addicts, fentanyl is their drug of choice.

For people who wish to wean themselves from fentanyl and its sibling opioids, whether due to physical dependence or addiction, the best path is generally understood to be opiate replacement therapy (ORT), also known as medication-assisted treatment. ORT dates back to 1965, when two physician-scientists at Rockefeller University, Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander, published a paper on methadone treatment for heroin addiction in the Journal of the American Medical Association. At that time, New York City was said to be home to 50 percent of all the heroin addicts in the country; all were regarded as criminals under the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914. In a remarkable departure from existing ideas about heroin addiction, Dole and Nyswander proposed that the addicts suffered from a chronic disease that could be corrected by an opiate—in effect, the addicts had been self-medicating, just with stronger doses when really they needed a different kind of opiate. The investigators chose methadone as a substitute because, while it has all of the properties of heroin, it is longer-acting and does not produce the same sharp highs and lows. Dole and Nyswander reported that addicts on stabilized doses of methadone “lost their craving for narcotics and appeared functionally normal in all respects.”

In the more than half-century since the birth of ORT, only one addition to the menu of replacements has been made: buprenorphine, approved in 2002. Like methadone, buprenorphine is an opiate with all the properties of an opiate: It is able to relieve pain, induce physical dependence, produce euphoria, and cause death in overdose. Its therapeutic virtue is that it is an opiate partial agonist, meaning it is less likely to suppress breathing and kill in overdose—think of it as Methadone Lite. A practical consideration is that, unlike methadone maintenance, which is conducted out of strictly controlled clinics, buprenorphine can be prescribed in an office setting by any physician who completes an eight-hour certification program. Howard Kornfeld has long advocated treatment of opiate addiction with buprenorphine, and likely would have recommended it for Prince.

Today, many thousands of addicts are maintained on buprenorphine or methadone for extended periods of time while measures are taken to address the underlying roots of their addiction, be they psychological or physical. However, many—perhaps even the majority—of those who treat addiction are opposed to ORT on the grounds that it is simply the substitution of one opiate for another. In their view, it is the opiate that is evil, not the addiction per se. As an alternative, these groups often employ methods developed in the 1930s by Alcoholics Anonymous. So-called 12-step programs feature the admission that one’s addiction is out of control, recognition of a higher power, and making amends for past errors.

Which model works better? Comparison of the success rates for abstinence-only versus opiate-replacement therapy is made difficult by the relapsing nature of addiction, an absence of standards for what constitutes success, and the absence of regulation for the addiction treatment industry. In the view of Dr. Richard D. Blondell, my colleague and vice-chair of addiction medicine at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, abstinence-only programs have a success rate of 15 to 20 percent. In 2006, a Cochrane analysis (the gold standard of medical efficacy) concluded that “No experimental studies unequivocally demonstrated the effectiveness of AA.” For those then entering ORT, however, 40 to 50 percent will recover. (Cochrane calls methadone “an effective maintenance therapy intervention for the treatment of heroin dependence.”) For patients such as Prince, who possess a high degree of motivation and substantial resources, recovery from opiate addiction is well within reach. For example, ORT programs treating physician addicts have success rates of 80 percent or higher.

Troublingly, though, a report issued by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, a nonprofit based focused on improving the treatment of addiction, points out that there are no national standards for the provision of addiction treatment. The center concluded that few addicts “receive anything that approximates evidence-based care.”* Furthermore, “most of those providing addiction care are not medical professionals and are not equipped with the knowledge, skills, or credentials to provide the full range of effective treatments.” Most states do not require that addiction counselors have advanced education of any kind. The worst of these programs perpetrate outright fraud.

In this sometimes sordid picture, where does Kornfeld fit? He is the founder of an outpatient pain management and addiction treatment program called Recovery Without Walls, located in Mill Valley, California, near San Francisco. Dr. Kornfeld is a fellow of the American Society of Addiction Medicine and well-recognized in his field, especially with respect to the use of buprenorphine both for chronic pain and as opiate replacement therapy. With respect to addiction treatment, the promotional materials for Recovery Without Walls stress an integrated approach combining buprenorphine with psychotherapy, nutritional support and vitamins, meditation, acupuncture, massage, and exercise.

Turning to Kornfeld and Recovery Without Walls was a logical decision for Prince, whether the intention was to relieve his chronic pain, wean him from physical dependence on opiates, or treat an opiate addiction. However, there are some peculiarities in Kornfeld’s response. In a news conference following Prince’s death, William J. Mauzy, a Minneapolis–based attorney representing the Kornfelds, said that Prince “was dealing with a grave medical emergency” and that “the doctor was planning on a lifesaving mission.”

If that was the case, though, a call to 911 in Minneapolis would have seemed a better choice than waiting for Kornfeld to send his son, Andrew, on an overnight flight from California—only to find Prince already dead. In addition, upon his arrival in Minnesota, Andrew Kornfeld had in his possession Suboxone, a drug combination containing buprenorphine and naloxone that treats opioid overdose. This fact immediately raised ethical and legal concerns in that Andrew Kornfeld, who has no medical qualifications, should not have been in possession of the drug, nor could he have legally administered it. Indeed, administration of Suboxone to a person physically dependent on fentanyl can lead to an intensification of pain and precipitation of withdrawal syndrome. Later, Andrew Kornfeld said that his intention was to deliver the drug to local physicians—an odd intent given that buprenorphine is available to any certified doctor in Minnesota.

The death of Prince was a profound loss for his family, friends, and millions of fans. The tragedy of his loss is compounded by the fact that it was preventable. We know now just how close he came to getting the help he needed, a feat in a medical system that does not yet embrace the most effective means of treating addiction. Why he didn’t get that help remains to be established, as does the source of the drugs that killed him.