A couple days after Patty Duke died from complications of intestinal perforation, I received a text from a friend feeling under the weather asking me, “Do I have sepsis?”

The answer was, mostly likely not. The reason I could say this is that my friend is a healthy person without multiple medical problems. Sepsis tends to happen to people who are already chronically ill with diseases like cancer or AIDS, have recently become very sick for other reasons (burn victims), or are unvaccinated. But, I understood why she was asking. Sepsis—defined as the body’s abnormal response to an infection that injures its own tissues and organs—maddeningly resembles normal responses to infection in otherwise healthy people.

And yes, sepsis can happen to anyone. Occasionally even the young and healthy get it. The good and bad news is that finding sepsis in otherwise healthy people is a needle-in-the-haystack endeavor: Americans suffer 900 million colds (perhaps the most common form of infection) each year, but there are only 750,000 instances of sepsis. That means that for every 1,200 colds, there is one case of sepsis. But finding it is critical: Of the unlucky few that get sepsis, between 16 and 49 percent will die.

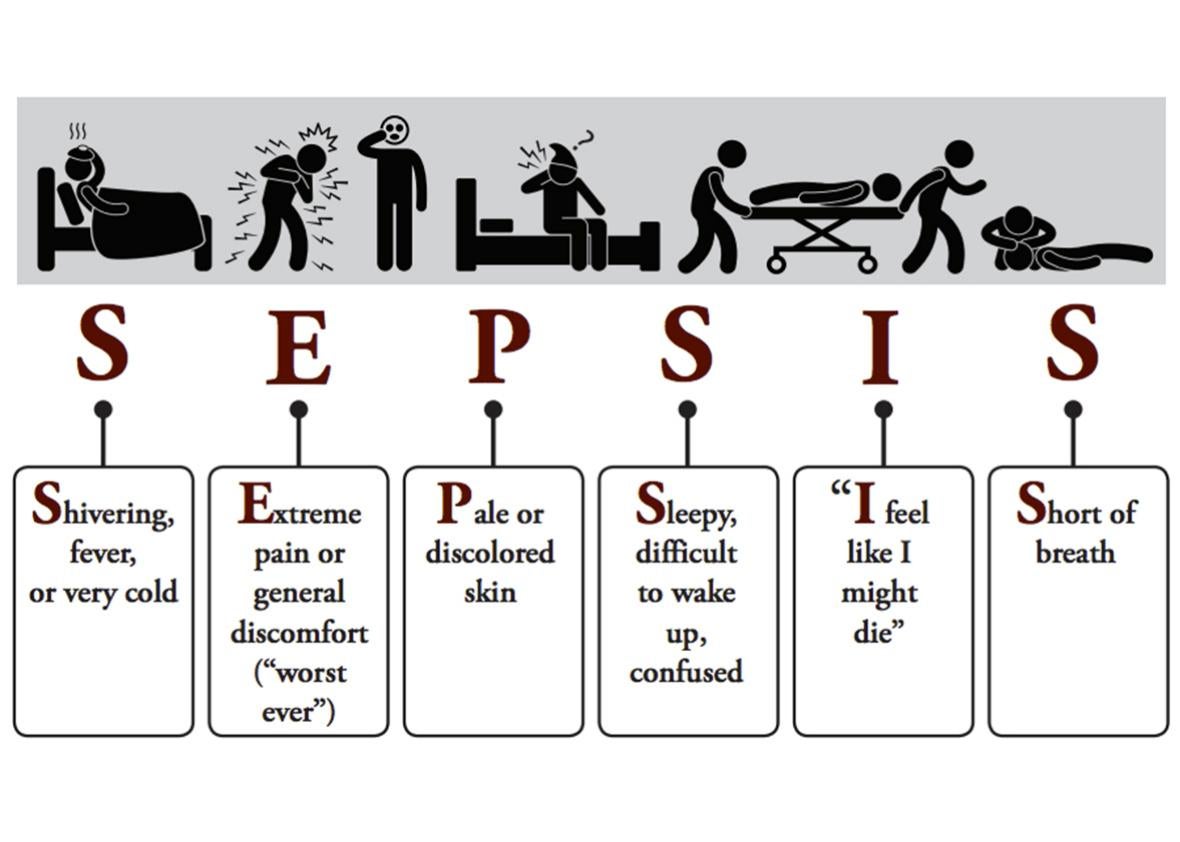

Unfortunately, the public messaging from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been a mess on sepsis. Until recently, the CDC failed to even mention sepsis in it’s A–Z index of medical terms. Then, following the tragic death of a 12-year-old boy named Rory Staunton, Rory’s parents successfully lobbied the CDC to add it. While the CDC’s new fact sheet is, indeed, largely factual, it would be hard to read it and other similar online resources without concluding that you need to run to the hospital every time you come down with a flu-like illness. For example, in response to “When Can You Get Sepsis?” the CDC explains: “Sepsis can occur to anyone, at any time, from any type of infection, and can affect any part of the body. It can occur even after a minor infection.” Additionally—in the sepsis acrostic, the I stands for “I feel like I might die.” (If you ever genuinely feel like you might die, please go to an emergency room immediately rather than consulting the internet.)

CDC

As bizarre as some of these recommendations are, it’s hard to blame the CDC. That’s because the medical community is currently debating just how, exactly, doctors should be screening for and diagnosing sepsis. In February, the top American and European societies of intensive care medicine officially confirmed what many of us had believed for a long time. It turns out that most of the commonly publicized “warning signs of sepsis” are red herrings. The old criteria known as SIRS—which includes fever greater than 100.4F, a heart rate above 90 beats per minute, a respiratory rate above 20 per minute, and a bunch of lab results—does a horrible job distinguishing healthy immune responses from septic ones. A person with any one of several hundred run-of-the-mill mild flu-like illnesses not only might meet all the SIRS criteria, they ought to. If you think about it, SIRS is so nonspecific that you usually have it after a workout (elevated respiratory and heart rate qualifies). But in patients actually fighting off an infection, serious or not, SIRS usually reflects appropriate immune responses. It is well known that SIRS overdiagnoses sepsis. But one recent investigation in the New England Journal of Medicine surprised many by finding that SIRS also misses up to 1 out of 8 severely septic patients. Now, doctors and nurses are instead being advised to look for three different features when screening for sepsis: altered mental status (meaning confusion), a systolic blood pressure equal to or less than 100 mmHg, and a breathing rate equal to or greater than 22 per minute. The presence of two of these appears to correlate to risk of sepsis severe enough to increase the odds of dying.

Unfortunately, many others in the medical community (including the federal government by way of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) are not on board with these new recommendations. They not only want us to keep using SIRS, they recommend immediately giving some of our heaviest-hitting “broad-spectrum” IV antibiotics to patients with SIRS and even the smallest abnormal findings in certain lab tests. The science behind the parameters the government has chosen to adapt has been seriously questioned, if not refuted. But that did not stop CMS from rolling out a disputed new sepsis “quality measure” last year all but requiring hospitals to treat such patients with broad-spectrum antibiotics, even if they don’t look remotely critically ill to the treating clinician. According to many reputable resources, government-funded and otherwise, if you have SIRS, you might be dying of sepsis.

It is understandable why CMS wanted to get in the sepsis game. After all, sepsis costs the U.S. more than $20 billion per year, and Medicare is the largest payer (of course, there is also the cost to human life). Back in 2013, CMS was convinced by a group of sepsis experts that a quality measure would save lives and money by detecting sepsis early and treating it aggressively using a rigid protocol. Other leading sepsis authorities didn’t agree: They worried the approach being considered was too invasive and didn’t allow doctors the flexibility they needed to best treat sepsis, while creating problems of overtreatment. Then, three highly anticipated studies were published in 2014–15 that mightily bolstered those skeptics’ arguments. These studies contradicted the mortality data that had persuaded CMS to move on its measure in the first place. Despite this, CMS decided to stay the course and rolled the measure out last year.

The strengths of the new sepsis definitions are that, according to the initial evidence, they appear to miss fewer cases while simultaneously decreasing overtreatment of the condition. And overtreatment is no small issue; there are major risks involved. First, antibiotics do not benefit patients with run-of-the-mill viral illnesses (which is what most mildly ill patients with SIRS have). Many patients who take antibiotics develop diarrhea and other side effects, some more worrisome than others. Some patients experience dangerous allergic responses to antibiotics that, though rare, can be life-threatening. Second, the more we use antibiotics, the more resistance develops. We know from the extensive literature, the CDC, the White House’s initiatives, and countless professional societies including the Infectious Disease Society of America that the more doses of antibiotics we prescribe, the faster resistant superbugs develop. The day of reckoning for this problem has not yet come, but we’re not doing as much as we could to ward it off. Since the new CMS federal regulation on sepsis came out, there have already been unusual shortages of the broad spectrum IV antibiotic imipenem-cilastatin, a major weapon in our armamentarium, and frequent “drug of last resort.” Some doctors have become so paranoid that they have lost perspective, even advising the painful placement of a “Foley” catheter into the bladder in order to detect sepsis-induced kidney failure. Such catheters are not the fastest, most accurate, or safest ways to detect sepsis-induced organ failure (a blood test is). But these catheters are an excellent and expensive way to cause it.

Hospitals may now be punished for not adhering to the CMS protocol. Moreover, CMS has now decided to ignore the new sepsis definitions. For the foreseeable future, CMS will continue to rely on SIRS for sepsis detection.

So, while the medical community continues to debate the best way to diagnose and treat sepsis, what can you do about it, other than staying up to date on vaccines that prevent some of the major culprits that cause sepsis?

Many sepsis awareness materials implore you to ask your doctor “could this be sepsis?” when you or a loved one feels ill. I would advise you to tweak this question slightly (it’s silly, but sometimes doctors don’t respond well to even the subconscious assumption that a patient is questioning their judgment). Instead, try: “What would it look like if this were sepsis?” That lets your doctor know you’re worried he or she forgot something and invites him or her to explain the process (doctors love to teach). The first question is often misunderstood by doctors as bothersome, or even uncooperative.

And remember, it is one thing to ask about sepsis. But demanding to be treated or even overtested for sepsis (or any infection) when a physician does not believe it will help is patently unsafe to both individual patients and society.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views and opinions of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.