The St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Homa Bay, Kenya, sits on top of a mountain that overlooks a glistening Lake Victoria. When I visited in mid-November, bookmark-size prayer cards were being distributed in anticipation of Pope Francis’ visit to Kenya in late November. The church has one of the largest congregations in a region that has one of the highest HIV infection rates in the world.

About one of every four people in Homa Bay is infected with HIV. The government has created public awareness programs and provides condoms. HIV drugs are available for free at the local hospital, and health workers go door-to-door encouraging people to get tested.

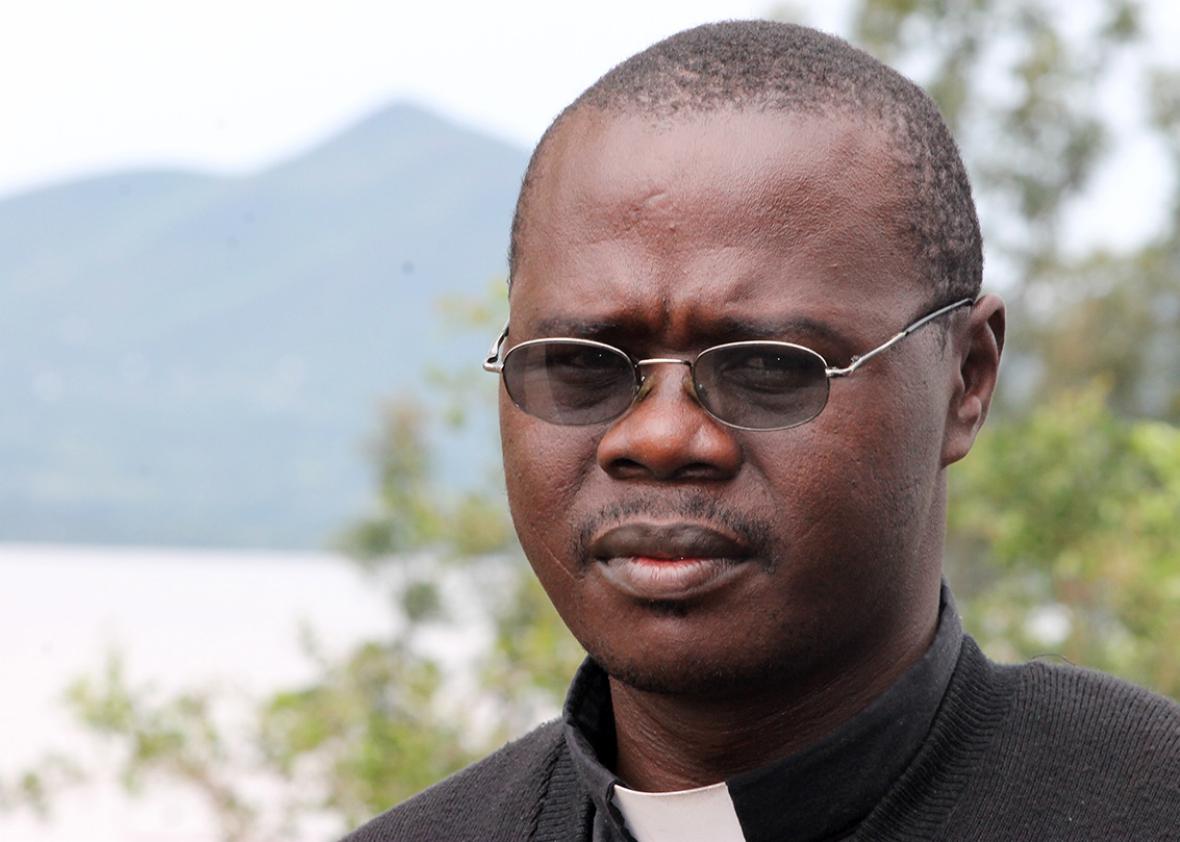

Yet the Catholic Church, where its intervention is needed most, has taken a fundamental stance against any use of contraception. The acting head of St. Peter’s, Father Gabriel Otieno, believes that condoms are actually causing the spread of HIV.

Every school holiday, the church holds seminars and tells local young people not to use condoms. “We educate the youth that the use of contraceptives is not in the mind of the church and not in God’s way of dealing with human beings,” Otieno told me as he sat in the church’s living quarters below a framed image of Pope Francis. He has the aura of a man practiced in preaching—even while speaking to one person, his voice rises and falls like an opera singer’s.

Otieno’s theory of why condoms cause HIV in Homa Bay goes something like this: Condoms are ubiquitous. Contraception creates a culture of uninhibited sex. After a while, the youth will stop using condoms but keep having sex. It means that more people will become infected with HIV.

When Pope Francis visits Kenya, Uganda, and the Central African Republic from Nov. 25–30, he will be visiting three countries with some of the highest HIV infection rates in the world, and three countries with large populations of Catholics, for whom condom use is not allowed. He could save lives here by reversing the Catholic Church’s rule. Some observers thought that Francis would at least relax the ban on condoms. He has not. The only church-approved method of contraception is abstinence.

Not all church leaders are so doctrinaire. In 2005, Archbishop Boniface Lele of Mombasa, Kenya, announced that married couples could use condoms to prevent HIV transmission. It was a defiant shift in the diocese, and researchers found that condom use more than doubled for the married couples who had access to contraception. If the Vatican changed its position and allowed condom use everywhere, the researchers speculated that the effect would be significant and widespread.

Lele died last year. When I talked to an official from his church about Lele endorsing condom use, he distanced his congregation from the policy. It was as if the church official believed that if he tried hard enough, he could wish Lele’s policy away.

Some local practices contribute to the spread of HIV. In Homa Bay, it’s tradition that when a woman is widowed, she is shunned from society until she is cleansed. She can’t fetch water or talk to anyone until she has sex with a family member or someone whose specific role is to sleep with widows. And if she’s Catholic, the man can’t use a condom.

“The church says there are no use of condoms, I feel very disturbed and pained because the woman will continue spreading HIV/AIDS,” says Sister Caroline Osogo.

Photo courtesy Justin Lynch

Osogo used to be a nun, but she left the Catholic Church 12 years ago for its stance on condoms and its other regressive policies. She is tall and wiry, like a lightning bolt that rises from the ground. Osogo hopes that Pope Francis will relax the Catholic church’s ban on condoms when he comes to Africa, just as he has been more accepting of the LGBTQ community. Osogo says that there have been priests and nuns who have died of AIDS; it’s lonely in the church, and they sleep together.

“It is high time the church should face this issue of condoms [and] protection in the Catholic Church from the human side of their feelings.” Osogo said.

Using condoms has been shown to reduce HIV transmission by around 80 percent. In Homa Bay, some Catholics ignore the condom ban due to the health crisis.

“Margarett” is a sex worker and is infected with HIV. (Her name has been changed to protect her identity.) Whenever she can, she says, she uses condoms because she wants to stop the spread of the disease. Unlike St. Peter’s Church, the Catholic church she attends encourages everyone to use condoms. The pastors in Margarett’s church say that even those in a committed relationship should use contraception—you don’t know if your partner has a “side dish.”

Religion has an important impact on sexual habits in Homa Bay, Janthi Pruce, the local project coordinator for Doctors Without Borders, told me. In 2013, Doctors Without Borders began to provide free testing for HIV, and the group sends health experts to meet with people who are HIV-positive to make sure they are using their drugs correctly. In partnership with the local government, residents get free HIV drugs.

The HIV prevalence for women who are 26 years old is 40 percent, according to a survey Doctors Without Borders conducted in 2012, and sex is common among young people. In some schools, contraception use has become a staple of the curriculum.

Yet youth outreach is also a cornerstone of Father Otieno’s seminars and sermons; he is trying to save the youngest of Homa Bay from a life of sin. It’s as if the youth of Homa Bay are a swing state in a campaign of deadly consequences.

After speaking with Father Otieno at St. Peter’s, I came across two teenage Kenyan boys in school uniforms trotting up the dirt road to school. One was tall and lanky, the other is shorter and more muscular. They were wary yet curious of outsiders, and both waved and said hello.

I asked them if their church allows condom use, and both appeared unsure of how to respond. The looming St. Peter’s Catholic Church seemed to collide in their minds with the public education programs they likely attended.

“No,” the shorter one answered, the church doesn’t allow condom use. As the two spoke more, they relaxed. They attend the local Catholic school. They like soccer.

Then the shorter one contradicted himself: His church does allow condom use.

The shorter boy became nervous, and it was clear that he wanted to say the right thing. Whether it’s with his pastor, his teachers, or a sexual partner, he probably just wants to do the right thing.

“Do you have any condoms?” he asks.