If you ever travel to Mogos, South Sudan, make sure to bring a water filter—not just because of the dirty water, but because of the dirty looks. The filter signals your participation in the fight against the Guinea worm parasite.

“It’s considered rude to be found wandering around without your filter pipe around your neck,” says Mark Siddall, principal investigator at the genomics lab at the American Museum of Natural History, which is currently hosting Countdown to Zero, an exhibit on disease eradication. “If you get thirsty, you’re risking someone else’s children.”

Guinea worm is a horrifying, ingenious little monster. Its larvae live in rivers and streams. When a person drinks contaminated water, the larvae transfer into the human host, maturing inside the body. The grown worm slowly migrates toward the skin surface, forming a large pink blister. The swelling throbs and burns, causing the sufferer to yearn for cooling water, which is exactly what the worm wants. As soon as the victim sinks his aching leg into a stream, the worm bursts forth to lay its next generation.

Photo by Louise Gubb/The Carter Center

For all its manipulative brilliance, Guinea worm has a weak spot. When in water, the larvae live inside of crustaceans called copepods. The copepods are large enough to be seen floating in a glass of water, and the weave on a simple piece of nylon is tight enough to filter them out.

The Carter Center has been waging a nylon war against Guinea worm since 1986, and we are tantalizingly close to global eradication. From 3.5 million cases in 21 countries in 1986, incidence dropped to just 126 cases in 2014, with more than half of those occurring in South Sudan. Vanquishing guinea worm would be arguably the first great public health triumph of the 21st century. It would also give new life to the human disease eradication movement, which suffered through 35 mostly frustrating years following the conquest of smallpox in 1980. The victory would prove to governments and private foundations that we can still accomplish eradication.

Resources are badly needed, because eradication is a costly and labor-intensive endeavor. Guinea worm is no exception. Volunteers regularly fan out through communities with picture books explaining the nature of the parasite and the need to always use a water filter. When someone develops a Guinea worm blister, workers meticulously track which water sources he might have drunk from or waded in. They also offer treatment—a gruesome and tricky tug of war with the powerful and persistent worm, which wants to come out only on its own terms. Pull too hard and the creature will snap, enabling the surviving portion to retreat back into the victim’s body. It takes weeks of painful tugging to remove the worm. Left untreated, guinea worm can cripple the sufferer, or lead to secondary infections and amputations.

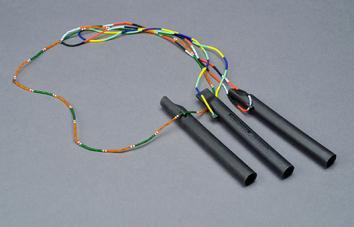

Perhaps because many people in South Sudan have fought epic battles with the Guinea worm, they have fully bought in to the eradication campaign. They’ve even contributed to the technology. The original water filters featured a pour-through system, which forced villagers to use multiple vessels when they wanted a simple drink of water. It was a villager—not a Western doctor or engineer—who eventually realized that an ordinary straw fitted with a tiny disk of nylon would be more effective. Since that small adjustment, water filters have become part of life in communities plagued with Guinea worm. In Mogos, villagers hang the filter pipes around their necks, and decorate the straps with traditional beads.

Photo by Denis Finnin/AMNH

The Guinea worm eradication program demonstrates the most critical part of an eradication campaign: togetherness. Look at the effort to eradicate polio—another disease inching toward extinction—and you’ll see that a unified front is just as important as the medical technology.

In 1954, more than 300,000 people across the United States volunteered to administer field tests for the polio vaccine. Nothing of that scale had ever been attempted in the history of U.S. medicine. Eighty million people donated money to the effort. More than 1.8 million parents offered their children as guinea pigs. They each received three injections over the course of five weeks, and many gave blood samples as well. When the trial was declared effective, on the 10th anniversary of Franklin Roosevelt’s death, the nation celebrated together.

Forty years later, in India (which is not known for its ability to get 1 billion people pulling in the same direction), the health minister for New Delhi convinced national officials that a mass vaccination campaign could work. The government brought doctors and nurses into the effort, but also recruited religious leaders, teachers, and Bollywood stars. Volunteers participated in “Polio Sunday” events, vaccinating children at train stations, religious festivals, and door to door. Against all odds and global expectations, they drove the proportion of unvaccinated children below 1 percent. Although conditions in parts of India are not remotely conducive to polio eradication—slum residents live tightly packed and drink extremely dirty water—the country has not seen a polio case in four years.

Photo by Louise Gubb/The Carter Center

Now look at the countries where polio still lingers, and you’ll see places riven by infighting: Nigeria, Somalia, Syria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. If we were a prescientific society, we would assume that polio is a disease caused by human disagreements and cured by public-spiritedness.

You must know where I’m going with this by now. The United States used to be a country where people worried about each other, and each other’s children. That was a vital part of previous eradication campaigns. Today we have hundreds of thousands of parents delaying or skipping vaccinations for their children. The only reason they have that luxury is that other parents do what they won’t: They get their own kids vaccinated.

“Measles was effectively eliminated from the U.S. at the end of the Carter administration,” says Siddall. “What changed? Where is our shared sense of responsibility? Our lack of a common purpose disgusts me profoundly.”

Let me tell you something: It takes a lot to disgust a parasitologist. This is a man who looks at worms all day.

In seriousness, the Guinea worm campaign shows us what African villagers can teach us about health care, and it’s not their herbal medicines. It’s simple teamwork and giving a damn about each other. Maybe they can inspire us.