One of the most shameful gaps in the American health care system involves the country’s poorest children. They can’t get basic dental treatment. It’s not that they don’t have insurance—many of them do. The problem is that dentists won’t treat them.

According to the Children’s Dental Health Project, an oral health advocacy group, 46.9 million kids are currently covered by Medicaid or CHIP, the government program that provides health insurance to children in families whose incomes are modest but too high to qualify for Medicaid. But in a recent survey, only 32 percent of dentists in private practice reported treating any patients on public assistance, and that figure is likely an overestimate.

Children who don’t see a dentist are more likely to miss school because of infected teeth and gums and to grow into adults with severe oral health problems. Dental disease only gets worse if it’s left untreated, and when people are unable to find a dentist to help them, they often end up in the ER. According to a study in the Journal of the American Dental Association, more than 4 million people went to hospital emergency rooms for help with dental problems from 2008 to 2010, at a cost to taxpayers of $2.7 billion, though the vast majority could get only pain relief there, rather than the dental treatment they needed. This is not only a poor way to provide care, it’s also outrageously expensive: A 2012 Pew report found that when Medicaid recipients go to the ER with a dental problem, the treatment costs the state nearly 10 times more than if preventive care had been delivered in a dentist’s office.

Dentists claim they just can’t help poor kids. Most dentists are small-business owners who run independent or small group practices. They say they can’t afford to work with Medicaid’s low reimbursement rates and administrative hassles or handle the high no-show rate of these patients.

One dental practice in Alabama is showing that there is a solution to these supposedly intractable problems. Jeffrey Parker is the CEO of nonprofit Sarrell Dental, where nearly 90 percent of the patients are children whose insurance is provided by Medicaid or CHIP. He is determined to challenge some universally accepted beliefs about public-funded dentistry, which he says are nothing more than “myths.”

One of these myths is that multisite clinics such as Sarrell are second-rate operations no one would go to if they had any other choice. His practice has racked up more than 600,000 patient visits in the past 10 years, and as Parker is fond of pointing out, not a single complaint has been filed to the Alabama dental board about Sarrell, nor have any errors been found in Medicaid audits. Sarrell provides the poorest children in the poorest counties of a poor state with top-quality dental care.

Photo courtesy of Sarrell Dental

Parker was a senior manager at General Foods, ConAgra, and Sara Lee before he became executive-in-residence at Jacksonville State University’s business school in 2000. In 2005, Warren Sarrell, a retired cardiologist who was trying to establish a clinic to address Calhoun County’s dental access issues, asked him for advice on how to make the practice sustainable. Parker, who thought he had retired from corporate life, originally intended to offer a quick consultation—but he never left. (Sarrell died in September 2012.)

A big guy in a workplace where most of the staff are petite women, and a rich man who runs an operation dedicated to serving the poor, Parker is a surprisingly good fit at Sarrell. Since he has much more business experience than everyone else there, and because he’s recruited many of the employees from JSU, where they first knew him as their professor, he’s very much the boss. Still, he loves to tease his colleagues—as we drove around Alabama, he took great joy in reminding Sarrell President Brandi Parris about the perm she sported when her high school volleyball team won the state championship—and he takes even more pleasure in being razzed himself: His favorite lunch spot is a barbecue joint where the waitresses serve up fried foods with a side of sass.

Parker is also a results-driven CEO. Still, when we sat outside his office, which is packed with sports memorabilia, including framed Super Bowl and Olympics tickets and a football signed by University of Alabama coach Nick Saban, he was positively gleeful as he unveiled a chart that would make most chief executives weep. On it, one line, representing the annual number of patient visits to Sarrell’s clinics, climbs upward to more than 140,000, while the other, which shows the average reimbursement per visit (almost entirely from Medicaid or CHIP, with minimal copays), plummets from $328 in 2005 to $124 last year. The drop-off is due to a combination of treatment and education. Once new patients’ cavities have been attended to, and bad oral health habits addressed, subsequent visits for cleanings and checkups generally cost taxpayers less. “There’s no business in the world that wants to say that every time someone comes into my store or my restaurant they spend less than they did the last time,” Parker says.

But he isn’t in the for-profit world anymore. The product he’s promoting is an innovative nonprofit business model for Medicaid dentistry. It’s working in Alabama, and now Parker wants to take the mission into other states. Unfortunately, the way dentistry operates in this country makes national expansion extremely difficult.

Sarrell is a nonprofit, but it’s self-sustaining—the clinics don’t use volunteers or take grants or cash donations. Sarrell has excellent equipment, hires top-flight dentists, and staffs its 16 clinics in a way that guarantees its dentists will take a close-up look at the work done by their fellow clinicians. The standard of clinical care is just about the same as in any other dental office in America. It’s everything else that’s different.

The differences in the Sarrell experience start long before patients arrive in the waiting room. The cornerstone of Sarrell’s strategy is to keep its dental chairs occupied as much as possible. “It’s Business 101,” says Parker. “If your revenues are declining—and, per patient visit, ours certainly are—there’s only one way to operate on lower margins, and that’s to see more people.” The quest to keep patients coming through the door begins with a community outreach team member, a role that’s unique in American dentistry.

One Wednesday morning this fall, I met Juliana Eraso in a packed church parking lot off Choccolocco Road, a few miles outside Anniston, where Sarrell has its headquarters. Officials from the Mexican Consulate in Atlanta make regular tours through Alabama, Tennessee, and rural Georgia so that Mexicans who live in those areas can renew their passports, obtain Matrícula Consular ID cards, and get legal advice; that morning the church was serving as a mobile consulate. A couple of banks were touting their services just outside the door, and an information table inside was stacked with laminated handouts about OSHA regulations and a Spanish-language pamphlet about the rights of LGBT students in public schools. But at that hour, Eraso, who’s in charge of Sarrell’s Hispanic outreach, was the only person staffing a table inside the building.

Eraso’s station was stocked with oral-health goody bags—brush, toothpaste, floss, mouthwash—and a Spanish-language activity booklet for kids. Along with a word search (cepillo de dientes, molares), a maze, and an oral-health-themed crossword, the booklet featured a centerfold cartoon about good brushing techniques. The mood was somber and a bit tense, as people waited for appointments, but Eraso was eager to tell the people sitting in folding chairs about the services Sarrell could provide to their U.S.-born kids. Indeed, like most of the outreach workers I spoke with during the week I spent in Alabama, she was possessed of an almost evangelical desire to spread the word.

The message Eraso and the dozen other members of the outreach team take to kids and their parents at festivals, fairs, rodeos, and summer sports camps around the state is educational—basic training on brushing and flossing and information about why it’s important to visit a dentist. But the mission extends to self-esteem building. Lindsay Frey, who runs community outreach for the Anniston and Talladega clinics, tells me that at the summer programs, when she gets to spend more time with the kids, “I try to be a mentor not just about their teeth. Telling them that they’re great at coloring might be the only good thing they heard about themselves that day.”

The outreach workers also go to schools, preschools, Head Start programs, and anywhere else children are found in order to demonstrate good oral hygiene and offer free on-site dental screenings. Sarrell staffers did 40,000 free screenings in 2013, and they’d like the chance to peer inside the mouths of even more young Alabamians. Frey tries to make it as easy as possible to set up a screening. Her tactics are aggressive—emailing, calling, or texting school nurses, teachers, and counselors, or hand-delivering permission slips to the teachers lounge. Medicaid dental coverage ends at the age of 21 in Alabama, and ALL Kids (CHIP) at 19, so developing good habits and taking care of cavities while kids are young can prevent years of problems and pain down the line. Of course, the screenings are also an effective way to identify potential new patients.

Photo by Juliana Jiménez Jaramillo

Once children have received one of these rudimentary exams, the responsibility for getting them into a Sarrell facility shifts from community outreach to call center. The appointment reminder call is as intrinsic a part of the American dentist-going experience as the paper bib or a gurgled, instrument-addled discussion of one’s vacation plans. Sarrell’s call center workers—typically, college students working the phones part-time—make those familiar calls, but they also contact parents whose children have been screened to see if they’ve followed up with their own dentists. If a family doesn’t already have a dental home, the call center workers will offer to make an appointment at Sarrell.

In each of the five clinics I visited, one to three young women kitted out in telephone headsets sat at desks and consulted computer screens. From a distance they appeared to be playing Tetris; upon closer inspection, it became clear that the spatial challenge was to fill in all the slots in their clinics’ schedules. It was hard for me to reconcile the phone bankers’ consistently perky attitudes with a task that seemed just one degree warmer than cold calling. Of course, it helps that this is one of the best-compensated of Sarrell’s nonclinical jobs. Since getting patients in dental chairs is key to Sarrell’s success, the call center workers receive incentive payments based on how well they succeed at keeping the dentists and hygienists busy. But the women who work the phones all assured me that it’s not a tough sell. Frey, who spends most of her time on outreach these days, sometimes chooses to make follow-up phone calls herself. “You’re calling to help a parent out,” she says. “Once they realize there’s no catch, they’re very grateful.”

Photo by Kayla Shipman

Once the call center sets up an appointment, and confirms the new patient’s Medicaid or ALL Kids eligibility, the kids are ready to visit a Sarrell clinic.

If “Medicaid dental clinic” summons a sense of desperation, it’s time to let go of some stereotypes. Whether a Sarrell office is located in a run-down neighborhood of boarded-up shotgun shacks (Bessemer, near Birmingham), in a public health facility (Talladega), in a generic medical complex (Anniston), stuffed into a cramped building in the back lot of a rural hospital (Boaz), or sharing space with a town hall out in the sticks (Leesburg), the clinics I visited were modern and pleasant. They’re all decorated with the same sunny decals of colorful animals, identified in English and Spanish. The waiting rooms are bright and well-organized, and although these are pediatric practices—which tend to be noisy even on Central Park West—a group of staffers known as “runners” does a fine job of controlling the chaos.

There is certainly a lot of movement in the Sarrell clinics. The Boaz office, which handles 19,000 patient visits per year, is the biggest Medicaid dental clinic in Alabama, and space is tight. Still, it’s a precision operation: Before children see a dentist, their height, weight, and blood pressure are measured and written down on slips of paper the kids pass along to their parents. (Although children on Medicaid don’t typically have the same difficulty getting to see a physician as they do a dentist, some Sarrell patients lack a “medical home.” Children with high blood pressure will be referred to a primary care provider, and the parents of overweight kids are reminded of the importance of healthy eating and exercise.) Family members are encouraged to sit in the treatment room and watch the dentist or hygienist at work. Although this sometimes means that a lot of people are packed into a small space, it teaches siblings—and some of the parents—that a dental appointment doesn’t have to be a scary or mysterious event. At Boaz and the other three locations that provide optical services, children whose pupils have been dilated walk around wearing paper-framed sunglasses.

Photo by Teresa Childers Stacks

Most of the staff are dressed in scrubs—even the folks who work the phones in the call center. Hygienists rotate out of chairside care for a part of the day to avoid repetitive stress injuries, and for the sake of efficiency, workers can be assigned to spend part of their shift in another role if the need arises. Alabama has a preceptor program for dental assistants and hygienists—which means they learn on the job, with some weekend classroom time, rather than passing a qualifying exam before they can practice, as is the norm in other states. That allows people who usually work in an office to occasionally take a turn assisting the dentists and thus accumulate hours toward a new career. (To promote this flexibility, every large piece of dental equipment is tagged with a QR code, which launches a homemade video demonstrating its use and maintenance.) Sarrell covers the cost of tuition for staffers who decide to pursue further education. I met a hygienist who used to work in a call center, several dental assistants who got their start on the business side of the operation, and a dentist who started out in the claims department and went on to graduate in the top 10 percent of her dental school class at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Graduates of Jacksonville State University, Parker’s alma mater and former employer, are heavily represented in the managerial and community outreach ranks, including many who took his courses at the business school before he stopped teaching in 2013. Jacksonville State isn’t an elite college, but Parker likes to recruit the best people from middle-tier schools, especially first-generation college graduates with “a bit of a chip on their shoulder.” Many of the staff managed stores or restaurants before they came to Sarrell. Previous experience in health care sometimes leads to “groupthink,” Parker says.

Photo by Teresa Childers Stacks

On the clinical side, it helps that Sarrell is, Parker claims, “the high-paying dental employer in the state.” The salary for a newly qualified dentist who works five days a week is $150,000—“way more” than the dentist would earn in private practice, and one of the highest starting pay rates in the entire country, he says. Crucially, the 19 full-time dentists and 20 or so more who work part-time for Sarrell don’t receive bonuses or incentives, which means there is no financial inducement to perform unnecessary procedures—a charge sometimes leveled against providers at for-profit chains.

The company has typically attracted top graduates from regional dental schools. But these days, Sarrell is doing less hiring straight out of school, because the economic climate is sending more experienced dentists into its fold. With private practice revenues down, as people cut back on dental appointments to save money, dentists are “quietly coming to us and saying, ‘Hey, I’ve got a day or two a month that I can work with you guys.’ The good news is, they’re going out to smaller, rural towns from their fancy practices and treating Medicaid children. And we’re getting great dentists,” Parker says.

When you hear how rare it is for private practice dentists to take on Medicaid patients, it’s easy to conclude that they’re selfish snobs prioritizing profit over the needs of poor kids. But it’s not that simple. There’s no question that Medicaid pays less than market rates, and as small-business owners, dentists can’t ignore financial considerations. Anyone with a limited number of billable hours each week would be sensible to fill them with the best-paying clients.

Photo by Teresa Childers Stacks

Dentists also have other reasons to be selective about the patients they serve. For people in good oral health, dentistry is an aesthetic pursuit. These people’s twice-yearly appointments typically consist of a cleaning by the hygienist and a thumbs-up from the dentist. Some dentists may prefer these quick and easy cleanings, with occasional elective procedures such as whitenings, over the complicated business of managing serious tooth decay and gum disease, which are more common among poor patients who may have missed out on good care as children. A dentist’s office has a lot in common with a fancy department store: The more expensive the clothes, the fancier the changing room, the more solicitous the saleswoman. Similarly, the higher a dentist’s fees, the more exclusive the waiting room. That’s why those dentists who do treat Medicaid patients often set aside a day just for them—it’s better for business to keep the two groups separate.

How does Sarrell handle the high no-show rates most providers claim they experience with the Medicaid population? Parker says this simply isn’t a problem. In the Anniston clinic, I met Jacqueline Marable, who had brought her six children in for appointments. She learned about Sarrell when her daughter Miracle took part in a screening at preschool, and it became the family’s first dental home. Marable had problems finding a dentist who would take Medicaid, let alone a practice that could schedule dental and eye exams for everyone in one afternoon, so she was happy to drive the 50 miles from her home in Roanoke, Alabama.

As for actually getting paid, government programs are Sarrell’s bread and butter, so, as a glowing report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation put it: “The billing department has extensive experience with Medicaid and CHIP. Claims are usually processed quickly and without error.” And the reimbursement rates? Every dentist and academic I’ve spoken with in years of researching the profession has told me that Medicaid should pay more, but Sarrell has proved that it can run a growing business in a state where the fees are less than generous.

Photo by Teresa Childers Stacks

Sarrell has also been willing to experiment with new systems for getting the best dentists in front of the neediest patients. Take scheduling. Dentists aren’t assigned to a specific clinic. Instead, they rotate among several offices. In part, this is a clever end run around the state’s challenging geography. According to Sarrell’s chief dental officer, Dr. Stephen Wallace, more than 90 percent of Alabama’s dentists live in the Birmingham area. Driving for 80 minutes each way to Leesburg or more than 90 minutes to Selma every day might not be sustainable, but once or twice a month isn’t so bad.

This means that patients don’t always see the same dentist, and that can be a good thing on both sides of the drill. Dentists get a close look at their colleagues’ work and at the treatment plans they’ve suggested for their patients. In a profession where diagnoses are always somewhat subjective, this means that every patient gets a second—and maybe even a third and fourth—opinion.

The uncommon setup also helps Sarrell recruit top talent. Although the dental profession tends to attract entrepreneurial types, not everyone wants the responsibility of running a practice, and for some, a nonprofit group setting like Sarrell is an attractive alternative. Cory Beattie White, a dentist who spends four days a week at Sarrell and then one day doing specialty restorations on adults, likes the lack of distractions. “I get to come to work and focus on treating children. If I need something, I just ask, and they get it for me. I don’t have to do marketing.” And it’s great work experience. Seeing so many different patients in varied settings means that “a year at Sarrell is the equivalent of five years in private practice,” she says.

Photo by Teresa Childers Stacks

Sarrell pays its employees well, and the clinics are well-equipped—some had high-end panoramic X-ray machines I’ve seen only in the swankiest of New York dental offices—but the organization also has a social justice mission “to be the national model for delivering quality and compassionate dental and eye care to underserved communities.” That affects the way it does business. In 2013, Sarrell provided about $800,000 worth of pro bono dental treatment, and as at many nonprofits, the staff are motivated by the knowledge that they’re doing good and helping poor kids. Unlike for-profit companies, Sarrell can prioritize filling the unmet need for dental care over the bottom line. Parker admitted that if finances were his chief concern, Sarrell’s clinic in rural Leesburg—the smallest in the practice, with 4,000 patient visits a year—might be considered for closure, but as a nonprofit, he can avoid that conclusion because “it wouldn’t be right for reasons of access to care.”

Sarrell’s lofty mission and its willingness to reimagine how dental practices work have not necessarily won it universal acclaim, however. The Alabama Dental Association, most of whose members are private practice dentists, challenged Sarrell’s right to operate as a nonprofit. In 2010, Sarrell sued ALDA, claiming the group was trying to put it out of business, and a 2012 PBS Frontline documentary included audio of ALDA members strategizing about closing down the clinic, which they saw as unwelcome competition. “What I’m scared about is there’s gonna be one at every Walmart in the South,” one unidentified dentist says on the tape. In 2011, after the lawsuit and an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission, the Alabama Legislature clarified Sarrell’s legal status, effectively ending the dispute. But it was a draining struggle, and Parker declined to comment on it.

Now Sarrell would like to take its model to the rest of the country, but it’s shut out of more than 40 states—because CEO Jeffrey Parker isn’t a dentist. To understand why so many states bar non-dentists from owning dental practices, you have to appreciate the peculiar way that American dentistry operates.

Traditionally, owner-operators have dominated the profession. In 1991, 91 percent of practicing dentists had an ownership stake in their practices, with 67 percent serving as the sole proprietor. Today, things are changing. By 2012 the proportion of dentists who owned their practices had dropped to 85 percent, with just 57 percent being solo practitioners. As I wrote in 2009, it’s tough to run this kind of operation. Owner-operators must buy their own equipment, supplies, and malpractice insurance; pay for rent and staff; and operate the kind of small business that can’t take much advantage of economies of scale.

Some dentists who can’t afford to buy a practice—in 2013, dental school graduates had an average of $215,000 in educational debt—or who just aren’t interested in running a business opt to work at safety net clinics. But a growing number are joining for-profit group practices. Dentists have always set up shop together, but in recent years, more outside business interests have gotten involved. In states where non-dentists are barred from owning practices, the most common arrangement is for companies, usually known as dental management organizations or dental service organizations, to manage the nonclinical aspects of a practice—scheduling, purchasing, billing, etc.—thus leaving the dentists to focus on providing treatment to their patients.

The dental establishment doesn’t approve of this development. Dental practice acts are determined on the state level, but in its official policies, the American Dental Association “supports the conviction long held by society that the health interests of patients are best protected when dental practices and other private facilities for the delivery of dental care are owned and controlled by a dentist licensed in the jurisdiction where the practice is located.”

Photo by Teresa Childers Stacks

That may sound like an effort to protect the business interests of its members, most of whom are still owner-operators. ADA President Maxine Feinberg says the rules about dentists owning practices are there to protect patients. “A dental board can only take action against a licensee” of that board, she tells me. “The fear is that if a corporate entity owns a dental practice, and there are problems that arise with the treatment of a patient, there’s no recourse.” A state dental board might not be able to adjudicate the problem, because it regulates dentists and not corporations.

With due consideration to the issues raised by Feinberg, the requirement that practices be owned by dentists in fact does little to protect patients. Instead, it contributes to a culture of duplicity: If for-profit chains want to set up shop in a state with ownership restrictions, some simply establish puppet owners so they can operate there.

There is no doubt that corporate dental chains have a bad reputation and that some provide substandard care. “Dollars and Dentists,” the Frontline documentary from 2012, alleged that dentists at the Kool Smiles chain were providing unnecessary and substandard treatment. (The same documentary heaped praise on Sarrell and its nonprofit model.) And earlier this year, a for-profit company called CSHM, which operates clinics around the country, mostly under the name Small Smiles, was barred from taking part in the Medicaid program after a string of allegations that it was performing uncalled-for procedures on young patients. But the existence of a few bad actors does not mean that multistate clinics run by businesspeople are inevitably corrupt.

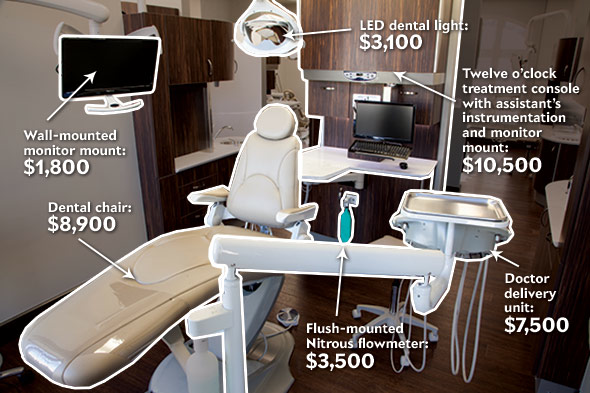

Source: Jim Connor/Burkhart Dental. Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo.

Similarly, critics who warn that financial incentives encourage corporate dental practices to undertake unnecessary treatments never seem to acknowledge that those incentives are just as strong—or perhaps even stronger—in private-practice settings. More procedures mean higher compensation in every kind of fee-for-service situation. In fact, employees of multisite practices that employ professional managers are surely less conscious of financial pressures than the solo practitioners, who are responsible for rent, payroll, insurance, and making payments on fancy equipment. Ultimately, whatever kind of setting they practice in, it is dentists’ professional ethics that keep them from providing unnecessary care.

Nevertheless, by restricting practice ownership to dentists, many states are effectively barring nonprofits like Sarrell, which are run by professional managers and have a chief dental officer overseeing clinical operations, from serving their low-income residents.

The dental profession as a whole has an outstanding record of prioritizing patients over profits. By emphasizing preventive measures—biannual checkups and cleanings, fluoridation of community water supplies, the use of fluoride toothpaste—and preaching against soda and candy, dentists have simultaneously saved their patients from pain and suffering and reduced their own incomes. We should thank them for that. Dentists have fared poorly in popular culture, where they’re usually presented as sadists, Nazis, bores, or failed physicians. In reality, they are heroes who have made it possible for millions of people to eat better, feel better, and look better. Because of their efforts, more people are entering their golden years with their own teeth than ever before. I remain convinced that I could never have had a career in the overwhelmingly upper-middle-class field of magazine journalism if it weren’t for the wonderfully skilled and patient Seattle dentist who spent a decade working on my teeth.

But many people, and not just the poor, are unable to get the basic treatment they need. About 130 million Americans lack dental coverage, and the rest aren’t off the hook. Dental “insurance” rarely covers the full cost of treatment: In 2011, $39.2 billion—46 percent—of the $85.2 billion spent on dental care came directly out of patients’ pockets. Dentistry is expensive enough that many people postpone procedures they urgently need—even though an abscessed tooth is excruciatingly painful and potentially deadly if infection spreads to the bloodstream.

There’s no single solution to America’s dental access problems. We need to do even more education and prevention work, increase Medicaid reimbursement rates, expand the dental workforce, integrate oral health into general medicine, and treat chronic tooth decay and gum disease using chronic-disease-management principles.

Photo by Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty Images

Sarrell is helping where it can. Last year it formed a partnership with DentaQuest, a large dental benefits provider and foundation, to create DentaQuest Healthcare Delivery, with Parker as CEO. In January the new company took over Community Dental Care, a struggling 14-clinic nonprofit dental practice in Texas, and in September it opened Community Dental in Kentucky after being invited into the state by the governor. DentaQuest’s CEO, Fay Donohue, tells me that Sarrell stands out as an organization that is making a difference in solving America’s dental access problem: “This is a model that works. There should be more kids in waiting rooms like [the ones] you saw, that are getting care that’s high-quality, cost-effective, and consumer-focused, patient-focused, family-focused.”

Expanding the Sarrell model by making it easier for nonprofit organizations to operate in every state would allow more of the nation’s 46.9 million children whose dental coverage comes from Medicaid or CHIP to get the care they need.

And it’s not just children who have unmet needs. Only 35.4 percent of working-age adults saw a dentist in 2012. As the baby boomers age out of employer-provided dental benefits, we need to find more high-quality, low-cost ways to provide dental care to everyone. By 2030, 72 million people, or 19 percent of the U.S. population, will be over 65, and those who will be relying on Medicare should remember that it doesn’t cover dental expenses. As people reach retirement age, they could find themselves facing sizable bills if they want to keep their own teeth. Clinics based on the Sarrell model could go a long way toward reducing the cost of care.

The millions of kids covered by Medicaid deserve a chance to get the kind of dental treatment middle-class parents are able to provide for their children. And the rest of the country deserves the same quality of care that the young people of Alabama find at Sarrell.