I threw up on a plane once. It’s not my favorite travel memory, but one that came up again during a recent flight, when I noticed that the seatback pouch in front of me was ill-equipped. SkyMall catalog? Check. In-flight magazine? Check. Plastic-lined receptacle for human vomit? Whereabouts unknown.

This was not the first time that my barf bag had gone missing. Now I have the queasy sense that these precious items may be in decline. I have no proof of this assertion, but anecdotes abound. Some friends and colleagues tell me that they’ve had the same experience: fewer bags on flights, they claim, nothing like the old days. In her latest online special, the comedian Chelsea Peretti describes the same experience: When one airline left her not-holding the bag at 30,000 feet, she threw up in a seat pocket.

Could this be another way for corporate bosses to save money? The major carriers, for their part, deny, deny, deny. I tried representatives at American, Delta, JetBlue, Southwest, and United: All said their crews still place bags in every seat on every flight, just as they’ve always done. Any bagless pouch would be the exception, not the rule. It’s certainly possible that sickness bags would seem less common to those—like me—who rarely seek them out. If I’m seeing bags less often than when I was a kid, maybe that’s because I’m less susceptible to nausea now, and not as prone to bouts of pouch-exploring boredom. Today they’re out of mind and out of sight.

Perhaps the bags are still around but barf is on the wane? The experts share my sense that we’re going through a great transition. “It’s been years since I’ve seen an air sickness bag being used,” said Steve Silberberg, owner of more than 2,500 unique specimens and one of the world’s most active air-sickness-bag collectors.

“Yes, bags are less common than they used to be,” agreed Paul Mundy, another major “baggist,” based in Germany.

“The last one I saw, a passenger had to ask for it. It’s the only one I’ve seen in 10 years,” said Brent Blue, a senior aviation medical examiner and member of the Aerospace Medical Association.

“Right now, air sickness is almost unheard of,” said Bob van der Linden, an aviation expert at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

If fewer passengers are joining the bile-high club, the airlines must know all about it. I’m guessing they keep track of bag replacement costs, and thus have some idea of whether air sickness rates are changing, but they keep those numbers secret. One company rep told me it would “raise issues of medical privacy” to share any such information (another example of the carriers’ well-documented concern for customer well-being). So we’re left to sort through public data, of which there isn’t much. The best numbers I could find come from a survey published in 2000, of about 1,000 people on 38 commercial flights. One-half of 1 percent said they’d vomited on the plane, and 8.4 percent reported feeling nauseated.

Common sense suggests that numbers were much higher in the past. Before the invention of the pressurized cabin, pilots could not fly at calm altitudes “above the weather.” Early planes were small and light by today’s standards, so they bounced around more in turbulence. The engines also made a racket and bathed the cabin in exhaust fumes. These problems gave rise to a brand-new medical condition, first diagnosed by a pair of researchers from Bordeaux in April 1911. “All progress is at a price; man pays a ransom for each of his adventures,” wrote Rene Cruchet and Rene Moulinier in their 1920 monograph. “The conquest of the air, besides its numerous dangers, is today resulting in a new disease, the disease we call air sickness.”

To counter this disease, early airline cabin crews often included a uniformed nurse. Paul Mundy says at least a few European airlines gave out paper sickness bags during the 1920s, which were tossed from open windows once they’d served their purpose. Some planes had barf bowls or cups, not bags. Mick Oakey, managing editor of The Aviation Historian, told me about a plane fitted out with wicker seats. The crew would fit a piece of china into a bamboo hoop beneath each chair.

A 1935 issue of Flight magazine describes a scene of flight attendants racing through the cabins with “charming, little papier-mache buckets” for green-faced passengers, but the modern, leakproof barf bag did not arrive until 1949. An inventor and ex-infantryman named Gilmore “Shelly” Schjeldahl started lining paper bags with plastic, and brought the notion to the Bemis Bag Co. in Minneapolis. His managers were skeptical at first, but changed their minds when the firm secured a contract for air sickness bags with Northwest Airlines. Schjeldahl—whose son Peter is now the art critic for the New Yorker—would be involved in many other major innovations, including the first passive communications satellite, but none was better-known than the “Air Sick Bag” that he helped put in airplanes. “He didn’t enjoy being associated with that,” says his widow, Charlene, now 97 years old. “It’s really strange.”

Yet even in the years before this barf bag spread, barf had become less common.

In the mid-1930s, a correspondent for Flight magazine wrote that air sickness “used to be the bane of air travel” but “is now comparatively rare.” The same magazine asserted in 1937 that “it is practically non-existent in these days,” as the early flaws in aviation had been mostly fixed. Not quite a decade later—and still four years before Schjeldahl would invent the plastic-lined emesis bag—an article in Flying magazine suggested that 0.2 percent of passengers were getting air-sick on commercial flights. In 1946, Popular Science gave the number as 0.3 percent.

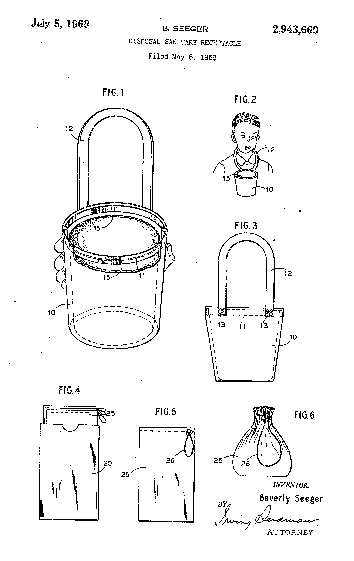

Image courtesy U.S. Patent Office

Compare those to the figures from 2000, and it looks like nausea rates bottomed out during the Truman presidency and have stayed pretty close to zero ever since. But the data are so sparse, and the method of collecting them so obscure, that no one in the barf-bag world takes them as definitive. A few experts in aeromedicine hinted that air sickness has continued to abate, and that improvements in the quality of planes and flight planning may not explain the whole effect.

What other factors could be at work? Perhaps we’re less often air-sick because we’re more frequent fliers. U.S. airlines carry about 750 million passengers per year, three times as many as they did 30 years ago. All that extra time in planes could help to cure a person of her motion sickness. As a general rule, the more time you spend in flight, the less sensitive you’ll be to getting sick. One study found that student pilots in the U.S. Navy vomited on 6 percent of all sorties, with rates falling off as cadets gained experience. The same effect could explain why children suffer more from motion sickness than grownups do: They’ve had less exposure, so fewer chances to adapt.

The lessening of motion sickness over time could reflect unconscious learning. Some scientists believe that motion sickness comes about from mismatched bodily sensations: Your eyes tell you one thing, and your inner ears tell you something else. The human sense of balance takes information from lots of other senses, too, such as the feeling of your blood (when it rushes to your head, you might think you’re upside-down) and the downward pull of your liver (which hangs from your diaphragm like a plumb line). If any of these signals are in conflict, you may start feeling dizzy, nauseated, or even tired and depressed. But given enough input, the brain can adapt to unexpected combinations.

It’s also possible, I think, that a change in sickness rates could start with something deeper—a shift of mindset and perspective on the act of flying. That’s not as crazy an idea as it sounds. In the 20th century, doctors sometimes blamed air sickness on a passenger’s personality. Cruchet and Moulinier warned that the “psychic overstrain” of air travel could lead to neurosis. In 1947 a Columbia University graduate student named Israel Zwerling wrote a dissertation on the psychology of motion sickness. For one experiment, he spun subjects around while giving them electric shocks. The more anxious they felt while spinning, the more nauseated they became. Follow-up work compared people’s tendency to nausea with their scores on Rorschach tests, and claimed to find some correlations.

Midcentury doctors blamed the sickness on two distinct causes: “motion and emotion.” Later researchers determined—or claimed they’d found—that women were more likely to get sick than men, and that Chinese people were more susceptible than Westerners. (There’s even one recent study that reports a link between motion sickness and the stage of a woman’s menstrual cycle.) I bring these up not because the data are convincing—I’d call them sketchy at first glance—but rather to suggest that motion sickness has a meaning and an etiology that extend beyond the physical phenomena of turbulence and fetid air. It could be that the barf bag caters not only to our bodies but our minds.

It’s telling that air sickness has an older sibling born not that many years before, and now mostly forgotten. “Railway sickness” was once so widespread as to necessitate a set of prophylactic superstitions: Some said you could keep nausea in check by carrying an Irish potato in your valise, or by stuffing newspaper underneath your shirt. Sigmund Freud thought the condition analogous to one produced in even older times, by the shaking of a carriage. Motion sickness, he argued, comes from the sexual vibrations that morph into nausea, anxiety, and fatigue by means of repression—“which turns so many childish preferences into their opposite.”

More modern explanations take into account the fact that railway travel was, at the time, quite dangerous. Gruesome accidents occurred with such regularity that the Victorians came up with a novel diagnosis—“railway shock”—to describe the PTSD-like illness that affected the survivors. It’s certainly possible that a latent fear of train travel functioned as the electric shocks in Zwerling’s experiments, to make passengers more susceptible to nausea. In recent years, Carey Balaban of the University of Pittsburgh has shown that neural systems underlying anxiety and motion sickness interact in a single portion of the brain called the parabrachial nucleus. “Panic disorders and balance disorders go hand-in-hand,” he says.

So it may be that each new conveyance brings along its special kind of nausea, as much an ache of modernism as a stirring of the inner ear. If that’s true, then the aging of technology would make the sickness less intense. When flying descended from the godlike to the commonplace, barf bags turned obsolete. Now they’re mementos of the golden age of aviation, a time when airplanes had the power to upset us, and when they still charged a ransom for adventure.

What’s next for motion sickness? Naturally, it comes up most often in the latest wave of future tech—video game consoles, tablets, and virtual reality environments. As for the barf bag, its fate may belong to the next frontier in human travel—as receptacles for lunar puke or other space emissions.