Hero means everything and nothing. It encompasses the firefighters who rushed into the burning twin towers, long-distance runners who compete through chronic disease, and the wag on Twitter who makes a point you agree with. The highly specific, armor-bright figure of classical myth has grown a thousand faces. We still want him around (DC Comics recently announced 10 new superhero films to unspool over the next six years, including one about a her: Wonder Woman), but his omnipresence makes him easy to mock. Part of our ambivalence may also stem from the suspicion that his noble deeds are not as selfless as they seem, motivated instead by a thirst for attention, rational egotism, or even masochism.

What’s the psychology of heroism? Is extreme self-sacrifice the result of a pained calculus, a weighing of desire and obligation, or an instinct? (Which would be more heroic? Does it matter?) In a study out last week in the journal PLOS ONE, Yale researchers recruited more than 300 volunteers to read statements by 51 contemporary “heroes.” These men and women had all received the Carnegie Hero Medal for “civilians who risk their lives to save strangers”; the experimenters wanted to know whether they had acted without thinking or after exerting “conscious self-control” in order “to override negative emotions like fear.”

The volunteers—and a computer algorithm, for safesies—analyzed the medal winners’ statements for evidence of careful thought, or of unpremeditated action. Overwhelmingly, they found that day-savers rescue first and reflect second. As Christine Marty, a 21-year-old student who wrested a trapped senior citizen from her car during a flash flood, said, “I’m thankful I was able to act and not think about it.” Study author David Rand noted that people playing economic games are similarly less likely to share resources when they ruminate about their moves, but more generous when they don’t take time to consider strategy. Perhaps human nature is reflexively pure and kind (and corrupted by our hyper-rational, transactional society)—or perhaps, as Rand speculated, cooperation becomes an intuitive habit only after we see it paying off. (Quoth Zazu: Cheetahs never prosper.)

The Yale study adds to a rich tradition of scientific inquiry into altruism, generosity, and the better angels/cannily perceptive salespeople of our nature. Before diving in, though, it’s worth noting that the hero and the altruist are made of slightly different stuff. While both act admirably, only one has, by definition, a superhuman, preternatural aura. That distinction raises the question of whether what we value in heroism is a kind of transcending of what we take to be our frail or selfish wiring. Generosity might retain its gleam if it’s innate—but does heroism count as heroism if we’re predisposed to it?

We may indeed be built for acts of kindness. Children engage in prosocial behavior early on, helping, giving, and empathizing. One-year-olds will comfort an experimenter in feigned distress. And a 2009 study by German psychologists revealed that 18-month-old toddlers often provide “spontaneous, unrewarded” help to adults, retrieving a dropped clothespin, for instance, or opening a cabinet for a researcher whose hands are full. It isn’t just that the kids like feeling useful or picking up clothespins. When the experimenter seemed unruffled by the fallen pin or the closed cabinet, rates of helping declined.

Of course, it doesn’t cost a lot to pick up an object from the floor (especially when you are 2 feet tall). So next, the researchers strewed obstacles between the clothespin and the child—complex motor movement is hard at that age!—and got the same results. Phase 4 was giving the child enticing toys to play with in one corner of the room and positioning the closed cabinet in the opposite corner. In order to do a mitzvah for the researcher, the toddlers had to leave behind the toys and walk precariously across the room. Many did. Nor did rewards for helping motivate them to help more. (In fact, suddenly introducing an extrinsic motivation can undermine the internal glow of doing good—and drive subsequent helping rates down. This overjustification effect is the bane of helicopter parents everywhere.)

Once we’re older, research finds, the impulse to be nice doesn’t go away. Brain scans show the activation of neural regions that process pleasure when we give to charity. Some people experience more activation—they find giving more pleasurable—than others. They are the ones who voluntarily donate the most in an experimental setting. (Stroke victims who suffer from lesions to selected brain areas may also exhibit pathological generosity.) But the question remains: Why do these so-called altruists take such joy in acting kindly?

One study, by researchers at Georgetown University, implies that the world’s givers and helpers simply possess more empathy. Psychologist Abigail Marsh and her team recruited 19 people who had donated their kidneys to total strangers, and 20 people who had not. They flashed images of fearful, upset, or angry human faces at the volunteers while recording their brain activity with an fMRI machine. The donors and the control group generated similar scans, except for two details: In donors, the right amygdala, which governs emotional response, was 8 percent larger, and it showed enhanced activity. Previous tests had already revealed the opposite finding for psychopaths. These empathy-impaired subjects had amygdalae that fired less when distressed faces were presented. Though fMRI studies are in their infancy, this one implied that altruists just give more shits than do the rest of us.

Yet perhaps they pursue generous deeds for craftier reasons. In 2012, psychologists from Knox College in Illinois divided 78 students into 26 groups of three—some with two men and one woman, and some with two women and one men. The groups were asked to complete a task that would result in a financial reward, and one facet of the job was that a team member would need to plunge his or her forearm into a bucket of icy water for 40 seconds. Within each group, the volunteer who elected to “sacrifice” him- or herself to the bucket (“This hurts a lot more than people think it will, and … even more after you remove your arm from the ice,” intoned the experimenter) was judged as more likeable and admirable than everyone else. That group member was also awarded more money when the teams decided how to split up their prize.

Perhaps predictably, intense rivalry broke out, especially between the men in male-male-female groups. Guys really wanted to wear the heroic, ice bucket-conquering mantle, gain social status, and impress the lady. The researchers concluded that engaging in “self-sacrifice” is “a profitable long-term strategy.” “Competition … and ‘showing off’ are key factors in triggering altruistic behavior,” they wrote.

Which brings us back to heroes. Despite all the prestige, money, and adoring lookers-on, at a certain point altruism no longer represents any kind of long-term strategy. Rather, its risks and sacrifices overwhelm its benefits.

The morbid, unspoken problem with studying real-life heroes is that they have a tendency to die. The three men who leapt in front of their girlfriends when a gunman opened fire in an Aurora, Colorado, movie theater can’t tell us what they were thinking and feeling. Nor can the Sikh temple president who lost his life shielding worshippers from a skinhead’s bullets. Nevertheless, a few papers shed some light. In 2005, researchers ran personality tests on 80 Gentiles who risked their lives to shelter Jewish refugees during the Holocaust, as well as 73 bystanders. Two interesting commonalities arose among the “heroes”: First, they were more likely to embrace, or at least tolerate, danger. Second, they were more likely to say they interacted frequently with friends and family. These findings expanded on a classic 1970 study of 37 Holocaust rescuers, in which researchers determined that the helping Gentiles were animated in part by “a spirit of adventurousness.” (Related but more prosaic: Studies suggest that “sensation-seeking” is positively correlated with the willingness to give blood.) In 1984, scientists John P. Wilson and Richard Petruska determined that “high-esteem” college students—those who believed they were worthy and competent—more often rushed to aid an experimenter during a simulated explosion, while “high-safety” students, driven by a need for security and the desire to avoid anxiety, were less likely to lend a hand. In the realm of smaller, but still substantial, risk, 74 percent of kidney donors interviewed for a 1977 study said they put great faith and trust in people, compared with only 43 percent of non-donors.

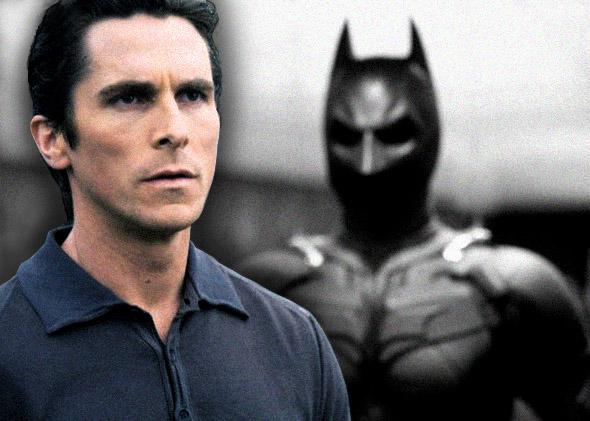

The heroic picture that emerges here—confident, risk-taking men and women who believe in others and value their relationships—looks familiar. It’s idealistic Peter Parker and grinning, goodhearted Indiana Jones. It’s Buffy, Wildstyle from The Lego Movie, and Law & Order: SVU’s Olivia Benson. Meanwhile, for show-offy altruists, there are philanthropic golden boys Bruce Wayne and Tony Stark, or that one male ally in your Twitter feed who always blurs the line between feminist support and benevolent sexism.

What about you or me? Will we be heroes when the moment calls? Maybe, if we don’t overthink it.