I would like to dedicate this article about narcissism to a very special person: me. This decision was not made lightly—only after I determined that there was no one else so incandescent, so charming, so wittily expert in the field of personality disorders as the one who appears in my mirror every morning, who in fact jumps out of every reflective surface I can unabashedly stare at during the day. Katy, this one’s for you.

Dedicating a story about narcissism to yourself is a pretty clever idea. I didn’t think of it. Jeffrey Kluger did, in his new book The Narcissist Next Door: Understanding the Monster in Your Family, in Your Office, in Your Bed—in Your World. Kluger’s well-researched and entertaining study of the syndrome du jour pulls in figures as varied as Lance Armstrong, Kim Kardashian, Jayson Blair, and Steve Jobs. It also names “exploitativeness” and “entitlement” as two of the narcissist’s calling cards, hence my ripped-off dedication. (“In keeping with the times: To me,” is his.)

Kluger is far from the first to observe that we live in a culture suffused by low-grade narcissism. Our Instagram accounts, Facebook pages, Twitter feeds, and personal websites refract our lives into a colored light show for all to watch. We come home from building our professional brands, fire up the Netflix stream of reality television, and bop our heads along to “Feeling Myself” by Will.i.am. (“Look up in the mirror, the mirror look at me. The mirror be like baby you the [best], goddammit.”) As I’ve written before, a 2008 study by the researcher Jean Twenge found that college students score higher on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory now than they did in 1979 and that more of them consider themselves “above average.” (Twenge has inspired a small cottage industry of debunkers and detractors, some of whom point to sinking crime rates and increased community engagement to show that young people ought to be pretty proud of themselves.) A study from the National Institutes of Health determined that 9.4 percent of 20- to 29-year-olds exhibit extreme narcissism, compared with 3.2 percent of those older than 65. You might argue that those results say more about youth than about our particular societal moment, but it’s almost a distinction without a difference—youth culture is dominant right now, with a bonanza of hit YA novels, highbrow cartoons, and exalted wunderkinds.

But for some experts, narcissism is more than a character flaw, a developmental stage, or an adaptation to social norms. It’s a diagnosis, inscribed in the bible of mental illness, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Narcissistic personality disorder belongs to a suite of personality disorders first codified in 1980. These diagnostic categories were controversial from the start, and psychiatrists continue to argue about how to define them and whether they should be in the DSM. Personality disorders are more subtle than schizophrenia, depression, or other classic psychiatric maladies, and as currently construed, they’re widespread: About 9.1 percent of Americans have a personality disorder. Borderline, obsessive-compulsive, and antisocial syndromes are among the most common; narcissistic personality disorder is estimated to afflict 1 percent of the population.

Patients with NPD display “pathological” traits such as grandiosity, self-centeredness, and a constant need for attention and admiration (the ego-feeding goodies known as “narcissistic supply”). Their relationships suffer as a result of impaired empathy, even as they rely heavily on others for “self-definition and self-esteem regulation.” Additional choice phrases from the DSM-5 criteria include “excessively attuned to the reactions of others,” “goal-setting is based on gaining approval from others,” and “firmly holding to the belief that one is better than others.” (For narcissists, “others” may be dullsville and inferior, but those others still end up twirling a lot of puppet strings.)

You can take a 40-question quiz to gauge your egomania. (Imagine the one-sided conversations: I got a 40! What’d you get? I don’t care.) But because your score ticks higher every time you agree with a statement like “I am a good leader” or “I like being complimented,” some say the survey, designed by psychiatrists Robert Raskin and Howard Terry in 1988, does a better job of reflecting self-esteem—or human nature—than narcissism. Just this month, researchers unveiled a simpler method for determining whether someone is a narcissist: Ask them, “Are you a narcissist?” “People who are willing to admit they are more narcissistic than others probably actually are more narcissistic,” explained Ohio State University psychologist Brad Bushman. “They believe they are superior to other people and are fine with saying that publicly.”

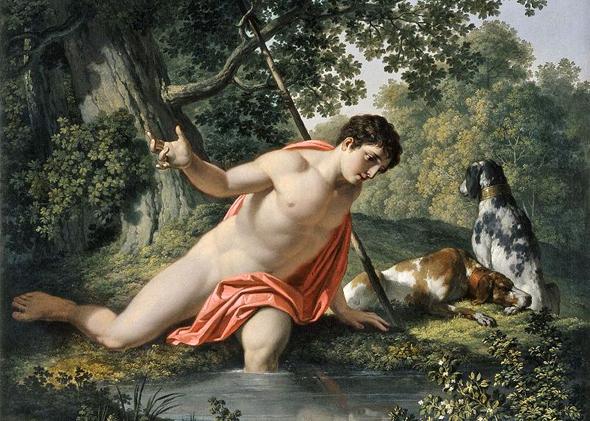

In order to qualify as pathological, narcissistic tendencies must impair functioning in real and painful ways. The self-absorption must not be explicable by age (toddlers are notorious tyrants) or socio-cultural environment (football stars are encouraged to act like Roman emperors). A true narcissist is all ego, unfettered and clumsy—he sees only himself, and yet the vision is opaque to him. He thrashes around in desires he can’t understand. Perhaps he loves No. 1 uncomplicatedly, or perhaps there is loathing mixed in. In her Harper’s piece “Me, Myself, and Id,” Laura Kipnis writes that the narcissist “lives as though surrounded by mirrors, but he doesn’t like what he sees.”

While this portrait may look familiar, it also has a slippery, everywhere-at-once quality. The looseness of the DSM symptoms (“personal standards are unreasonably high in order to see oneself as exceptional, or too low based on a sense of entitlement”; “over- or underestimation of own effect on others”) and the proliferation of subtypes (“fragile,” “amorous,” “compensatory,” “paranoid,” “phallic”) make it all seem uncomfortably broad. I think of Virginia Woolf’s warning: “It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality.” When you create a label, the label can acquire a life of its own.

This might be happening with narcissism, Kipnis argues. For all their cultural ubiquity, narcissists are elusive figures. They are us in the aggregate and sometimes her but never me. Kipnis points out that the vampiric, spotlight-stealing narcissist has historically been introduced to explain why we normals aren’t getting the attention we deserve. The floridly conceited Christopher Lasch couldn’t understand how his Harvard roommate, John Updike, appeared to sail so effortlessly into renown. So he wrote The Culture of Narcissism. In the 1970s and 1980s, narcissistic patients had one symptom in common—they made their therapists feel underappreciated. (Kipnis cites an analyst who found his narcissistic clients distressingly “demanding, controlling, tyrannizing, insatiable, and destructive.” “You start to wonder whether the shrinks are the ones who need validation and affirmation,” she remarks.) Today they are co-workers, acquaintances, and lovers whose rampaging egos trample our own poor yearnings underfoot. What if condemning others for narcissism—for failing to give us what we need—is how we avoid facing our own insignificance? What if the word is just an accusation we hurl when we feel lonely, anonymous, unloved?

While Kipnis builds a seductive case, you get the sense she has underestimated narcissists. “Personality traits exist on a continuum,” says John Oldham, chief of staff at the Menninger Clinic and one of the leading voices for getting NPD into the DSM-5. “Someone with narcissistic personality disorder is at an extreme point on the continuum, a point that leads to incredible impairment at work, interpersonally, and socially.” In subclinical patients, self-confidence (the healthy isotope of narcissism) may shade into arrogance, but not Trump-level radioactive hazmat. Pure NPD, Oldham says, makes “people’s worlds fall apart.”

For psychiatrists, the question isn’t really “do narcissists exist” or “are narcissists any different from the rest of us.” It’s “are narcissists mentally ill?”

Behind this question lurks another one: What do we gain, and lose, from picking out a psychic phenomenon and declaring it “sick”? Are we needlessly stigmatizing ordinary behavior? Absolving jerks of responsibility for their trespasses? Conversely, given our more advanced understanding of mental illness as biological—a complicated interweaving of genetic, developmental, and environmental factors—are we being more humane? Making it easier for people who are suffering to find treatment?

“We all have a tendency—greater or less—to be selfish, and I don’t see it as helpful to discuss ‘narcissism’ and ‘narcissists’ in diagnostic terms,” writes the psychologist Peter Kinderman in The Conversation. His problem with the mental illness label: It is inaccurate, a contrived category for a pervasive human impulse. Our shared penchant for narcissism plays out to greater or lesser degrees, he claims, and we should concentrate on how “we all, me included, can be self-centred, lacking in compassion, lacking in empathy.”

Yet it seems strange to insist that, because small-N narcissism lives in everyone, narcissistic personality disorder can’t inhabit its own pathological real estate on the far end of the continuum. Anxiety disorders exist, though we all get anxious. And just as mental illness itself has undergone a transformation from perceived moral failing to medical ailment, perhaps we can begin to see certain persistent dispositions as disabilities rather than spiritual flaws.

Psychologists are largely in the dark about what causes NPD. A study of 175 volunteer twin pairs (90 identical, 85 fraternal) suggested that narcissism is a highly heritable trait, but few labs have looked at what triggers the full-blown personality disorder. Adoption studies of antisocial personality disorder support the claim that environment plays a role in this roster of illnesses. Some experts posit that NPD, which tends to manifest by early adulthood, sprouts from “excessive pampering” or a self-serving parental “need for their children to be talented and special.” The most common causal model, however, imagines a skein of interrelated biological, social, and psychological factors, in which a predilection lurking in your DNA may flower heinously with the right combination of childhood experiences, learned behaviors, and nurtured quirks.

One reason personality disorders are so challenging may be that qualities like narcissism seem too close, too innate, to fit under the mental illness umbrella. Your depression or anxiety does not have to define you, but your personality might. Traditionally, the biological view of mental disorders is seen as kinder than its alternatives (“There’s something wrong with your brain! It’s not your fault.”), but it also implies a kind of life sentence, an irrevocability. Subjecting your very character to judgments of sickness or health has the potential to sear pathology into the core of your identity.

Doctors are pushing back on that sense of hopelessness and stigma. “One definition of illness is ‘something we treat,’ ” says Andrew Skodol, a psychiatry professor at the University of Arizona and a specialist in NPD. Yes, he continues, narcissism is treatable. Especially in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy can relax the grip of the disorder and nudge patients closer to the safe middle of the spectrum.

In fact, narcissism’s responsiveness to treatment may be the strongest argument for including it in the DSM. When you are suffering from something you can’t quite control and that professionals have insight into managing, the best thing to do is seek help. Fewer people will attempt to grapple with their narcissism if they do not consider it a disorder. Skodol’s utilitarian argument for pathologizing self-centeredness is based on these two facts: Personality traits appear to be partly inborn, though malleable—that is, they are conditions rather than choices—and therapists can guide narcissists through the hard process of containing their egos and building their lives.

For Skodol and Oldham, recognizing NPD as a “condition” does not mean releasing narcissists from accountability for their actions. “Even if you have a mental illness, you have to do your best,” says Oldham.

As it stands, many doctors are still dissatisfied with the DSM-5’s portrait of narcissism. A recent paper points out that the description, with its brief and broad list of symptoms, overlooks the nuances of the syndrome’s nature (from normal to pathological), structure (as a category but also a dimension), presentation (are you grandiose or painfully vulnerable?), and expression (is your narcissism overt or kept hidden?). Yet including the condition in America’s field guide to psychological disorders is a good thing. Whether they are maligned for being selfish sons-of-bitches or considered mentally ill, narcissists will probably face a measure of stigma. They might as well get some help too.