This article originally appeared in the blog Aetiology.

It’s odd to see otherwise pretty rational folks getting nervous about the news that the American Ebola patients are being flown back to the United States for treatment. “What if Ebola gets out?” “What if it infects the doctors/pilots/nurses taking care of them?” “I don’t want Ebola in the United States!”

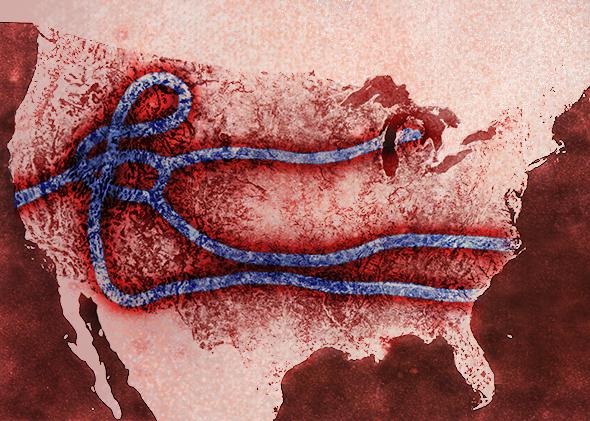

Friends, I have news for you: Ebola is already in the United States.

Ebola is a virus with no vaccine or cure. Any scientist who wants to work with the live virus needs to have biosafety level 4 facilities (the highest, most secure labs in existence, abbreviated BSL-4) available to them. We have a number of those here in the United States, and people are working with many of the Ebola types here. Have you heard of any Ebola outbreaks occurring here in the United States? Nope. These scientists are highly trained and very careful, just like people treating these Ebola patients and working out all the logistics of their arrival and transport.

Second, you might not know that we’ve already experienced patients coming into the United States with deadly hemorrhagic fever infections. We’ve had more than one case of imported Lassa fever, another African hemorrhagic fever virus with a fairly high fatality rate in humans (though not rising to the level of Ebola outbreaks). One occurred in Pennsylvania, another in New York just this past April, a previous one in New Jersey a decade ago. All told, there have been at least seven cases of Lassa fever imported into the United States—and those are just the ones we know about, people who were sick enough to be hospitalized, and whose symptoms and travel history alerted doctors to take samples and contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s not surprising this would show up occasionally in the United States, as Lassa causes up to 300,000 infections per year in Africa.

How many secondary cases occurred from those importations? None. Like Ebola, Lassa is spread from human to human via contact with blood and other body fluids. It’s not readily transmissible or easily airborne, so the risk to others in U.S. hospitals (or on public transportation or other similar places) is quite low.

OK, you may say, but Lassa is an arenavirus, and Ebola is a filovirus—so am I comparing apples to oranges? How about, then, an imported case of Ebola’s cousin virus, Marburg? One of those was diagnosed in Colorado in 2008, in a woman who had traveled to Uganda and apparently was sickened by the virus there. Even though she wasn’t diagnosed until a full year after the infection (and then only because she requested that she be tested for Marburg antibodies after seeing a report of another Marburg death in a tourist who’d visited the same places she had in Uganda), no secondary cases were seen in that importation either.

And of course, who could forget the identification of a new strain of Ebola virus within the United States. Though the Reston virus is not harmful to humans, it certainly was concerning when it was discovered in a group of imported monkeys. So this will be far from our first tango with Ebola in this country.

Ebola is a terrible disease. It kills many of the people that it infects. It can spread fairly rapidly when precautions are not carefully adhered to: when cultural practices such as ritual washing of bodies are continued despite warnings, or when needles are reused because of a lack of medical supplies, or when gloves and other protective gear are not available, or when patients are sharing beds because they are brought to hospitals lacking even such basics as enough beds or clean bedding for patients. But if all you know of Ebola is from The Hot Zone or Outbreak, well, that’s not really what Ebola looks like. I interviewed colleagues from Doctors without Borders a few years back on their experiences with an Ebola outbreak, and they noted:

As for the disease, it is not as bloody and dramatic as in the movies or books. The patients mostly look sick and weak. If there is blood, it is not a lot, usually in the vomit or diarrhea, occasionally from the gums or nose. The transmission is rather ordinary, just contact with infected body fluids. It does not occur because of mere proximity or via an airborne route (as in Outbreak if I recall correctly). The outbreak control organizations in the movies have no problem implementing their solutions once these have been found. In reality, we know what needs to be done, the problem is getting it to happen. This is why community relations are such an issue, where they are not such a problem in the movies.

So, sure, be concerned. But be rational as well. Yes, we know all too well that our public health agencies can fuck up. I’m not saying there is zero chance of something going wrong. But it is low. As an infectious disease specialist (and one with an extreme interest in Ebola), I’m way more concerned about influenza or measles many other “ordinary” viruses than I am about Ebola. Ebola is exotic and its symptoms can be terrifying, but also much easier to contain by people who know their stuff.