Last month, a spellbinding 10-hour debate to legalize physician-assisted dying took place in Britain’s House of Lords. Since Americans are unfamiliar with this legislative body, it bears mention that most peers in the upper house of Parliament have been appointed for life for their experience in public service or for their outstanding level of achievement in a given field. Accordingly, many of the bills introduced are not shackled by political constraints, as is the case in the U.S. Congress, but instead address urgent social issues that warrant and receive thoughtful consideration.

Lord Falconer of Thoroton convened a committee to draft an aid-in-dying bill, HL 6, based on the 1997 Oregon Death with Dignity statute. The proposed U.K. bill would allow doctors to prescribe a lethal dose of oral barbiturate medications to terminally ill, mentally competent patients judged to have less than six months to live.

Three states in the United States have such laws (Oregon, Washington, and Vermont) and two others (Montana and New Mexico) are not criminalizing the practice, but many states have laws against assisted suicide with penalties for families or physicians of up to 10 years imprisonment. The House of Lords debate barely rated mention in the American news media. That may be because there is an almost impenetrable taboo in our country surrounding death-hastening decisions. We can learn a lot from the recent discussion in the United Kingdom.

In the lead-up to the debate, Lord Carey, the retired Archbishop of Canterbury, shocked his church by declaring he could no longer condone “needless suffering” and now supported legalization.

“If we truly love our neighbors as ourselves,” he explained,” how can we deny them the death we would wish for ourselves?”

The backlash was swift and predictable. The Bishop of Carlisle and the present Archbishop of Canterbury claimed that if the prohibition were to be lifted, there were “risks and dangers” that many thousands of vulnerable elderly and infirm individuals would be pressured to prematurely end their lives.

The bishop of Worcester, John Inge, then poignantly recounted during an interview the circumstances of his wife’s death from abdominal cancer on Easter Day.

“If assisted dying had been legal,” the bishop stated, “how tempting it would have been for me at that stage—or later, as the dreadful effects of chemo took their toll and I became more and more worn out with caring for my wife and two children and distressed at seeing her in such pain and discomfort—how tempting it would have been for me to have suggested to her that it would be ‘for the best’ for her to end it all there and then.”

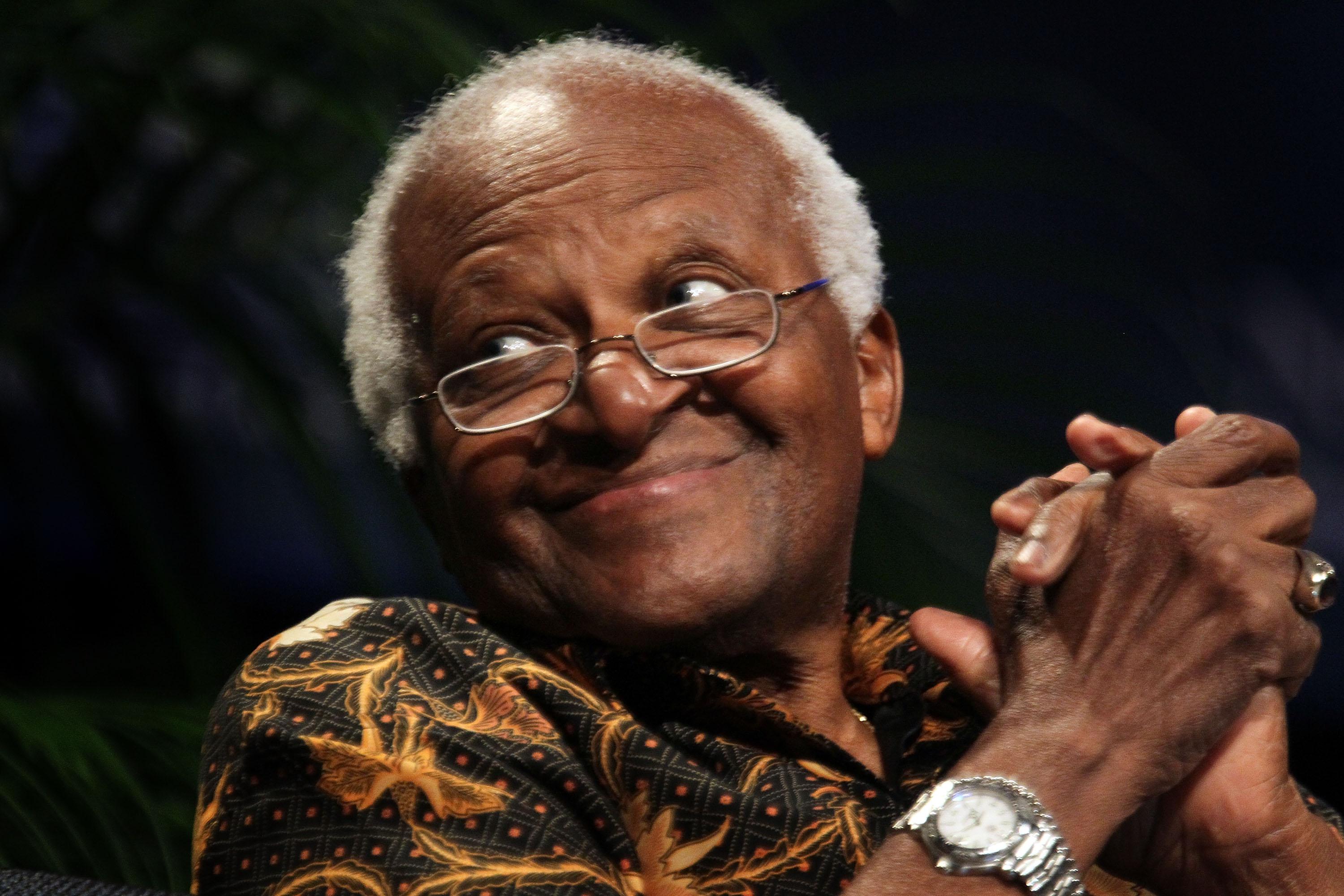

Just as the British public was reacting to these pre-debate sentiments, Desmond Tutu, one of the world’s most highly respected moral leaders, declared he was backing Lord Falconer’s bill.

Writing in the Observer, the 82-year-old retired Anglican archbishop from South Africa said laws preventing people from being helped to end their lives are an affront to both them and their families. He had arrived at this position following the “self-delivery” (suicide) of a young, desperately ill South African man, Craig Schonegevel. Tutu also took the opportunity to condemn as “disgraceful” the treatment accorded to his friend, Nelson Mandela, who was kept alive through numerous painful hospitalizations and propped up for a photo shoot with visiting politicians shortly before his death at age 95.

“I have been fortunate to spend my life working for dignity for the living,” he wrote. “Now I wish to apply my mind to the issue of dignity for the dying. I revere the sanctity of life—but not at any cost.”

This same opinion was unexpectedly echoed that week by Stephen Hawking during a BBC-TV broadcast. The famed physicist, who has a motor neuron disease, said through a speech-generating device, “If you have a terminal illness, and are in great pain, I think you should have the right to end your life. … It is discrimination against the disabled to deny them the right … that able-bodied people have.”

When the debate in Parliament finally ensued, Lord Falconer addressed the assembled: “My Lords, in the last stages of a terminal illness, there are people who wish to end their life rather than struggle for the last few months, weeks, days or hours. Often it is not the pain that motivates such a wish, but the loss of independence and dignity. … The current situation leaves the rich able to go to Switzerland [where assisted suicide is legal], the majority reliant on amateur assistance, the compassionate treated like criminals and no safeguards in respect of undue pressure.”

As his colleagues took turns speaking, their voices sometimes quivered with age and the anguish of conviction. Both thoughtful and emotional arguments volleyed back and forth in the oak-paneled chamber.

Baroness Nicholson warned that the National Health Service would be transformed into the “National Death Service,” and doctors would become “executioners.”

Lord Avebury said, “As a Buddhist, I recognize that this Bill contravenes fundamental Buddhist beliefs in the inviolability of human life, but there is also the Buddhist principle of compassion, which I think applies in the extreme circumstances of distressing terminal illness.”

Baroness Campbell spoke from her wheelchair with the aid of artificial respiration. “This bill is about me,” she said. “I did not ask for it and do not want it but it is about me nevertheless … [It] gives no comfort to me. It frightens me, because in periods of greatest difficulty, I know I might be tempted to use it.”

Lord Harris optimistically announced, “[The Bill’s] passing is as clear a mark of social progress as this week’s Church of England decision allowing the appointment of female bishops and the 2013 legalization of equal marriage.”

Lord Tebbit cautioned, “This bill is a breeding ground for vultures, individual and corporate. It creates too much financial incentive for the taking of life.”

During the debate in the House of Lords, a record number of members addressed the chamber—62 peers spoke up in opposition and 65 in support. While Lord Falconer’s bill is unlikely to become law during this session of Parliament, it has now officially passed the second reading and is moving to the committee stage. There it will be scrutinized, amendments proposed, a report issued, and it will eventually move to a third reading before possible passage. Whatever the bill’s fate, the debate has both raised awareness and educated the public about an increasingly crucial issue.

Paradoxically, aid in dying has more to do with living than with dying. It is most relevant in affluent countries like the United Kingdom and United States where many citizens are likely to die slowly of the infirmities of age and progressive illnesses rather than suddenly of violence and accidents. The debate in the House of Lords was about—and conducted by—people who have been fortunate to be able to make choices throughout their lives. The result is, perhaps ironically, something that Congress seems unable to achieve these days: an actual dialogue that has the potential to transform rancor into the sort of respectful disagreement and mutual sympathy essential to a successful democracy. One can but hope every country—including the United States—will achieve a national conversation about how we want to die, and this can occur with the wisdom, honesty, style, and eloquence that were on display in London.