Legislators in Washington state refuse to live in a world where only the wealthy can afford care from poorly trained health care providers who practice unproven medicine. This year Washington joined Oregon and Vermont in covering naturopathic care under Medicaid. Now every Washingtonian, regardless of means, has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of quackery. And taxpayers are footing the bill.

Medicaid coverage is the result of a series of anti-scientific decisions many states have made. The whole mess began with an argument within the community of naturopaths. Many acupuncturists, herbalists, and practitioners of ayurveda have been working for decades without formal training or licensure. As it became clear that there was money to be made in the field, four-year naturopathic colleges sprang up and expanded. Their graduates, who can spend more than $150,000 for their educations, wanted to distinguish themselves from untrained naturopaths, so they lobbied state legislatures to create a licensing system. Many states acquiesced—over the objections of traditional naturopaths—believing that they were protecting consumers. Currently, 18 states and the District of Columbia license naturopaths.

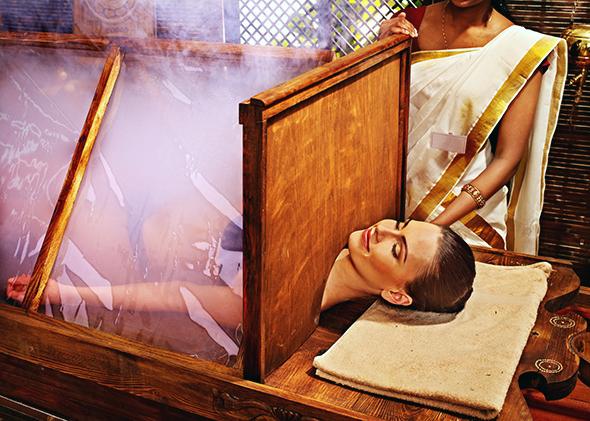

This was a serious mistake. Naturopathic medicine isn’t a coherent discipline like otolaryngology or gastroenterology. Take a look at the curriculum at Bastyr University, one of five U.S. schools accredited by the Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges. Botanical medicine, homeopathy, acupuncture, and ayurvedic sciences are all on the course list. The only thing that these approaches to medicine share in common is that they lack a sound basis in evidence. Differentiating between trained quacks and untrained quacks is not actually a consumer protection measure.

Once state governments recognized naturopathic medicine as a legitimate practice, the naturopaths wanted more. They are now lobbying hard for what they call “non-discrimination” among health care specialists. Since they’re licensed like real doctors and nurses, naturopaths want to charge like real doctors and nurses and get reimbursed like real doctors and nurses. This is an exploitation of the word “discrimination.” Treating things that are fundamentally different in a different manner—for example, covering proven therapies but not disproven or unproven therapies—isn’t discriminatory, it’s sensible. To equate it with real discrimination is an insult to people who have actually suffered.

The tactic, however absurd, has succeeded in Washington, Oregon, and Vermont. Now naturopathic lobbyists are working their black magic on the federal level. Their man in Congress is Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin, one of quackery’s best friends on the Hill. Harkin was the driving force behind the creation of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Harkin’s monster devours money that could be used for cancer, infectious disease, and neuroscience research and gives undeserved credibility to long-disproven therapies. (That’s not the federal agency’s official mission statement—I’m interpreting it for you.) Harkin also apparently micromanaged the process to ensure that actual science didn’t undermine his agenda. When Joseph Jacobs, who ran a previous version of NCCAM in the 1990s, resigned his post, he told Science magazine that Harkin had pressured the agency to fund pet projects and ignore the evidence. In fairness, Harkin isn’t a hypocrite—he really believes in this nonsense. He once claimed that bee pollen cured his hay fever. The manufacturer of his miracle cure was later fined by the Federal Trade Commission for false claims (surprise!), but that doesn’t seem to have deterred the indefatigable Harkin.

Sorry, I’ve gotten sidetracked making fun of Tom Harkin again. Where was I? Right, Harkin slipped a “non-discrimination” provision into the Affordable Care Act, at a late stage of the legislative process, when it would not be reviewed in committee. The provision states that health insurance providers “shall not discriminate … against any health care provider who is acting within the scope of that provider’s license.”

Federal agencies have struggled to interpret the provision. Last year a joint document issued by several federal departments suggested that insurers may legally exclude some providers from coverage if the decision is consistent with “reasonable medical management.” Harkin’s Senate committee rejected the interpretation, which would allow insurers to “exclude from participation whole categories of providers.” Regulators are now trying to decide how to reconcile their view of evidence-based medicine with Harkin’s vision for medical care.

As a point of clarification, there is little chance that private insurers will be required by law to pay for herbal medications or acupuncture. Medical doctors wouldn’t receive reimbursement if they delivered those services, so denying reimbursement to naturopaths doesn’t represent “discrimination” in Harkin’s world. The problem is that insurers may be forced to pay naturopaths to provide the kinds of services currently provided by actual medical doctors—consultations and the like. A recent article in the Seattle Times told the story of a couple now saving $95 under Medicaid each time they take their toddler son to a naturopath, and it noted that Washington’s naturopaths are licensed to prescribe antibiotics.

Exposing the holes in naturopathic medicine is a bit like taking candy from a baby, but this is a super-annoying baby, so let’s have some fun. The widely respected Cochrane Collaboration has produced dozens of articles comprehensively reviewing the evidence for alternative medical practices. In virtually all of the assessments, the authors conclude that the evidence is too weak to say whether the therapies have any effect. In 2011, for example, the group assessed the validity of ayurvedic medicine in treating diabetes—exactly the kind of chronic ailment for which some people seek out a naturopath. The researchers found that a handful of studies suggested that ayurvedic herbs may lower blood glucose levels, but those studies were methodologically flawed. “There is insufficient evidence at present,” they concluded, “to recommend the use of these interventions in routine clinical practice.”

Many naturopaths insist that their expertise is preventive medicine—a selling point of the Affordable Care Act—but most of those claims are either untestable or wrong. Many naturopaths encourage their patients to take antioxidant supplements to stave off cancer. The large-scale studies that have addressed this issue overwhelmingly show that the strategy doesn’t work. Green tea, another darling of naturopaths, is similarly ineffective at preventing cancer. Consult the Cochrane database for further debunking enjoyment.

I’m all for choice, but we share the cost of health care collectively. People who contribute to Medicaid and private insurance pools should know that their money is going to good use. We can’t say that for naturopathic medicine. If people want to see a medical practitioner who lacks appropriate training and advocates for unproven treatments, they should pay for it with their own money.