Modern physicians may give medical advice to their family members or, in a pinch, write them a prescription for a low-risk medication. (They’re not really supposed to, but it happens.) But most would never take charge of a relative’s care, especially for a serious disease.

The American Medical Association agrees, writing in its 1993 Medical Code of Ethics that “physicians generally should not treat themselves or members of their immediate families.” “Because a clinical encounter with a family member is not a typical doctor-patient relationship,” a 1999 ethics case study advised, “physicians caring for family members may tend to ignore standard guidelines, such as respecting a patient’s right to decide about treatment, informing the patient about the risks and benefits of treatment and plausible alternatives, telling patients the truth and respecting confidentiality.”

But over a roughly 25-year span, my father, Phillip I. Lerner, acted as the primary doctor for his relatives several times. He recorded some of the details and his rationale in his journals. Reviewing these cases for a book on my dad’s career in medicine, I was perturbed and even appalled at some of his decisions. Yet, I had to ask myself: Were there lessons here for modern physicians? After all, it is hard to imagine any patients receiving more intimate care and attention than did these relatives.

My father did not set out to become the family’s doctor. It simply emanated out of the type of physician he was. Trained at a time when residents practically lived in the hospital, and were mentored by senior physicians who viewed patient care as a 24-hour, seven-day commitment, my dad had no tolerance for what he believed was inadequate or incompetent care. He spent hours during our family vacations on the phone with covering physicians and insisted that we travel only at the end of the month. It was then, after his younger colleagues had spent at least two weeks getting to know the patients on the service, that my father finally felt comfortable going away.

The first time my father intervened was in 1975, regarding the care of my maternal grandfather, Mannie, who was in his mid-70s and mildly demented. When Mannie suddenly developed ischemic bowel, in which part of his intestines were not getting blood, the only option was emergency surgery, which was risky and might not succeed. As far as I can tell, my dad unilaterally—without asking my grandmother or mother—decided that surgery would not be done and Mannie should be made comfortable. “The only thing I can say,” my dad later wrote, “is that he was failing very quickly and this had to be the best way for him and for Nana.”

This “doctor knows best” mentality embodied the paternalistic ethos that had long dominated medicine. The new bioethics movement, with its emphasis on patient autonomy, was still in its nascent stage in the mid-1970s. Yet by intervening so blatantly in the care of a family member, my dad was not only being paternalistic but also had a conflict of interest: He was acting as both a son-in-law and a doctor.

In 1982, my father’s uncle Mickey became ill. The news was grim: Pancreatic cancer that had spread to the liver. Blurring the line from the start, my dad—not Mickey’s own doctor—gave Mickey the diagnosis and prognosis. During Mickey’s final hospitalization that summer, my dad visited him every day to make sure his uncle was getting adequate palliative care. He stayed in Cleveland with Mickey instead of driving me to New York, where I was beginning medical school.

Four years later, one of his aunts, who had cancer and lived in a nursing home, was admitted to the service being run by my father. My dad argued strongly against aggressive interventions, writing that he was trying to perform “passive euthanasia.” This time, however, his colleagues called him out. The house staff, he wrote, objected to his “minimalist approach.”

In the early 1990s, my father’s cousin Donald developed metastatic prostate cancer. My dad was very involved, making suggestions and writing prescriptions—especially when his cousin was having difficulty reaching his doctors. “I suddenly find myself taking care of my cousin Donald,” he wrote.

Later, when the pain from the bony metastases had become severe, my dad believed that Donald’s primary physician was not treating his cousin’s pain aggressively enough. He called Donald’s wife to urge her to tell that doctor to “ease” Donald “out of this terrible suffering.”

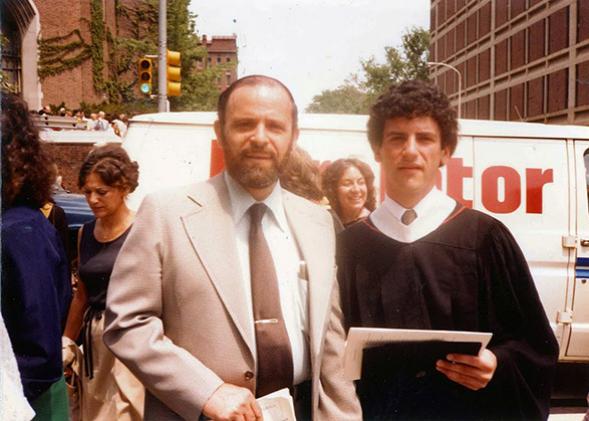

Family photo courtesy of Barron Lerner

But it was with my two grandmothers where my father truly became too involved, aggressively pushing for interventions that had as much to do with his being a relative as a doctor. In 1997, Pearl, his 88-year-old mother, suffered a bleed in her brain that left her comatose with no chance for recovery.

All of the physicians agreed that the prognosis was grim, but that was not enough for my father. Pearl’s worst fear, which she had often stated, “was to have a stroke and have to live a limited existence, dependent on others for her basic necessities.” For my dad, every minute she lived in a coma was a betrayal, causing her to linger in a way she had vehemently rejected.

I never figured out exactly what happened in Pearl’s hospital room, but it seems pretty clear that my dad—either with the help of the nurses or not—somehow sped his mother’s death with intravenous morphine. In his journal, he vaguely wrote that he had been able “to help her achieve the peaceful end she sought.”

Even more disturbing was the case of my maternal grandmother, Jessie, Mannie’s wife. As of 2000, Jessie, then 93, had been living for years with an astounding number of maladies. Not only was she blind and mostly deaf, she had coughing spasms, stress incontinence, “horrendously itchy” eyes, back pain, and chronic diarrhea.

When she was admitted to the hospital for a heart attack and congestive heart failure, my father once again pushed for palliative morphine as opposed to treatment of the acute condition—what he later referred to as “meaningless treatments that wouldn’t change the ultimate outcome.” What was especially worrisome was why my father had made this decision. Even though Jessie had never termed her life unbearable, he had decided that no one that miserable could genuinely want to undergo aggressive measures. Moreover, he cited the negative impact of Jessie’s illness on my mother, who was her primary caretaker. Bringing Jessie back home, he wrote, would have taken an unacceptable physical and emotional toll on his wife.

Perhaps because it was 2000, and the era in which senior physicians could unilaterally dictate patient care had ended, Jessie’s caregivers pushed back. Her “quick final exit” became stalled, my dad wrote in his journal, “when the staff rebelled at my pushing the dose of morphine.” On at least one occasion, it seems, the nurses lowered the rate of the morphine drip when my father dozed off. A couple of days later, Jessie’s heart finally stopped of its own accord.

As a practicing physician myself, and one who had studied the history of medicine and bioethics, I had no doubt as I reviewed his journals that my father had crossed the line. What I had thought at the time had been corroborated by his journals. No matter how much he believed that Jessie—and my mother—were suffering, he did not have the right to use this reasoning to try to speed Jessie’s death. As far as I could tell, he never specifically asked Jessie or my mother about whether to treat the congestive heart failure and try to get Jessie home.

And yet, reflecting on these episodes, it was hard not to be impressed with what my father did. He was using his accrued knowledge and skill to provide care to the very people he loved the most: his mother, his mother-in-law, and other relatives. Not only did he understand the medical problems at hand and their potential treatments, but he also knew about the pitfalls of care: how patients fell through the cracks, could not reach their physicians, and suffered from inadequate pain management. My dad was glad to help Donald, for example, because it gave his cousin “a little more control” and allowed him to “avoid unnecessary treatments” and minimize visits to doctors.

And in his general inclination to do less and not more for patients with a poor prognosis, my father was ahead of the curve. I have seen many patients like my grandfather Mannie reflexively taken to the operating room without any discussion of the odds of survival or the arduous nature of rehabilitation. I have seen physicians either too reluctant or too busy to discuss less aggressive options at the end of life. The idea that such a scenario would befall his relatives was intolerable for my father. Remarking on how he was so often asked to provide yet another course of antibiotics to end-stage patients with dementia or cancer who had no chance of meaningful recovery, he wrote that “My talents prolong the lives and sufferings of strangers.” Never, he added, would he “do things like this to a loved one!” In justifying his desire to get Donald more aggressive palliation, my dad wrote “I am most concerned that his suffering end as soon as possible, so we can remember him as he was, the Donald all knew and loved so much, not the Donald who suffered so at the end.”

In our modern era of ethics committees, hospitalists and intense documentation, physicians can no longer care for relatives as my father did. Today, if doctors wish to intervene in their family members’ end-of-life care, they must indicate their concerns to the colleagues who are their relatives’ primary caregivers. My father’s excesses—especially with my grandmothers—remind us why this strategy is far preferable.

But let’s not forget the good my dad did. At the shivah for my father, who died in 2012, Donald’s wife came up to me and gently grabbed my shoulders. Recalling my dad’s efforts 20 years earlier, she told me, gratefully, “he practically lived at our house at the end.”