My wife Lisa doesn’t cherish the fact that this story begins by disclosing her recent acne flare-up. But given the wider public health implications, she’s given me permission to write about the stubborn collection of pimples on her left cheek that didn’t respond to her usual skin care. It is, after all, the problem that led to a prescription drug arriving on our doorstep a couple of weeks ago without a prescription. A drug she’d purchased from one of America’s largest retailers, Amazon.

Lisa wasn’t searching the dark alleys of the Internet for something illicit. While she was scrolling through the acne treatments available on Amazon, where she rocks her Prime account like a boss, the site served her up something she wasn’t looking for and didn’t know she wanted, an acne treatment called Vitara Clinda Gel. Several happy Amazon customers had raved about it in five-star reviews. But once her purchase arrived from a third-party seller in Thailand with “Gift” scrawled across the customs declaration tag, she got suspicious. Then she read the label. “Hey isn’t clindamycin a prescription drug?” she asked me, a physician.

Clindamycin is indeed a prescription-only antibiotic that we don’t use lightly even in the hospital, where it’s known to set off potentially deadly Clostridium difficile diarrhea after killing good gut bacteria, and it sometimes provokes a severe allergic skin reaction called Stevens–Johnson Syndrome. It’s available as a prescription gel for tough acne vulgaris infections, but it’s something I’d leave to the dermatologists and wouldn’t prescribe to someone like my wife for a few pimples. So how’d she get it so easily from Amazon?

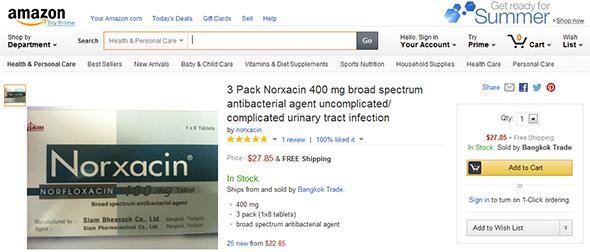

I have by no means executed a comprehensive search of wares sold by Amazon directly or through its third-party sellers, but I found other prescription drugs for sale without a prescription, including the antibiotic norfloxacin and the muscle relaxant methocarbamol. Both compounds, like clindamycin, warrant careful oversight to avoid complications or endangering public health, such as by breeding antibiotic resistance. Methocarbamol, which causes a mild high, can be abused and can prove deadly when mixed with alcohol. Selling these drugs without a pharmacy license and without a prescription is flat out illegal.

Which is precisely what the FDA and U.S. Customs and Border Protection had in mind last week when their agents descended on international mail facilities in Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago, seizing hundreds of packages containing illegally distributed prescription drugs on their way to American consumers. The FDA also found 1,975 websites illegally selling medications to U.S. consumers as part of “Operation Pangea VII,” an international effort coordinated by Interpol. The agency sent Internet service providers warning notices about the illegal activities taking place on their servers.

Screenshot

The FDA didn’t respond to questions about whether any of the seized goods were purchased via Amazon. Last year CBP intercepted 4,821 packages containing medications illegally imported by Americans without prescriptions at international mail facilities across the country, the agency told me. It conducts its enforcement operations in conjunction with FDA and the Department of Homeland Security. The numbers represent a drop in the ocean.

The type of illegal drug sales on Amazon happens to be well suited for avoiding CBP scrutiny, says James Cannon, president of the Customs and International Trade Bar Association, who spoke with me in his capacity as a partner with Cassidy Levy Kent, a top international trade law firm. “They know they’re going through these massive distribution centers where carriers bring everything in the middle of the night and there’s so much volume it’s very difficult to look at everything. Customs inspects, but it’s more like random sampling,” Cannon told me. Enforcement would work better if there were a “whistle-blower” that called attention to it, and then CBP could go specifically looking.

CBP likely wouldn’t prosecute the individual American consumer, who might not even understand they’d made an unlawful transaction, Cannon adds. The target would need to be Amazon, which created and profits from its marketplace connecting consumers to illegal medical products from around the world. In the case of the clindamycin my wife received from Thailand, Amazon made 15 percent off the sale.

Which federal agency has responsibility for policing Amazon? CBP operates on the ground in shipping facilities and ports. Investigating Amazon’s business practices would be up to the FDA, and that agency would then direct CBP to take any necessary actions on its turf.

I spoke with Gary Yingling, a former FDA attorney who is now a partner with megafirm Morgan Lewis. “In my view there’s no question FDA has jurisdiction because you’re talking about a prescription drug and you’re talking about importing it into the United States,” Yingling says. He points out that FDA has limited resources, and violations are everywhere. A more typical joint FDA and CBP action occurred with one of Cannon’s clients, a multibillion-dollar pharmaceutical company with a factory in Germany. CBP seized one of the German factory’s large U.S. shipments because the factory’s FDA-issued manufacturing license had expired. This was an easy spot for the FDA to flex its muscle: halting a declared shipment on an established trade route from a registered factory. It’s far more difficult, and even impractical, to intercept shipments from all over the world to tens of thousands of individual consumers.

In order to slow this trade, the FDA would have to target a major player in the complex shipping network, Amazon, by issuing a secret “untitled letter” or a public “warning letter” to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. In response to questions about Amazon, the FDA replied to me that Amazon has been the subject of consumer complaints, but that it has not been “the subject of any warning letter or enforcement action.” The FDA did not explain why Amazon has not come under publicly revealed scrutiny and declined to comment on whether Amazon has been the subject of untitled letters, which are not public.

Yingling notes that the FDA must be ready to engage in a fierce legal battle, as “Amazon’s not going to be willing to change their business instantaneously just because I’m the FDA.” The teeth backing up those letters is the threat to seek a court-ordered injunction against the business model, which could lead to a consent decree forcing Amazon to change its business permanently.

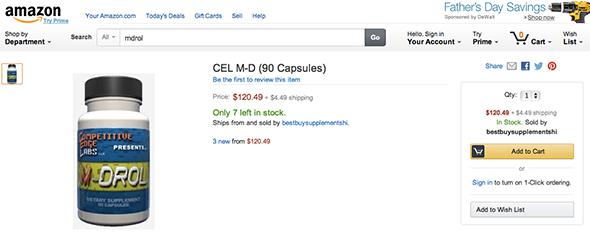

So why does Amazon risk such disruptive and expensive government action that could rock its stock price? A look at the company’s longstanding, profitable business selling anabolic steroids sheds some light on Amazon’s apparent feeling of invincibility. The FDA seems to have a blind spot for the online commerce champion. The agency overlooked sales of the same dangerous products on Amazon when it went after BodyBuilding.com for anabolic steroids in 2012, according to Oliver Catlin, CEO of the Banned Substances Control Group, which tests commercially available supplements for illicit compounds banned in sports, such as anabolic steroids. Catlin provided Slate with screenshots he took of Amazon products dating back to 2010, two years before the FDA levied a $7 million fine against BodyBuilding.com and a separate $600,000 fine against its president. The screenshots reveal Amazon selling M-Drol in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 and P-Plex in 2012, two of the steroids that led the FDA to crack down on BodyBuilding.com.

When BSCG discovered anabolic steroids for sale to anyone on Amazon back in 2011, the Washington Post reported on its findings. Catlin now admits he was naive to think the company would change its ways. “Frankly we’ve been looking behind the scenes for a while and it really bothers me there’s no action,” he says. “From my perspective, for the FDA to go after a distributor the size of BodyBuilding.com and close down that outlet and then leave open America’s largest distributor to sell the very same products is a complete hypocritical application of the law.” He watched dumbfounded as steroid products BSCG had tested and reported in 2011 reappeared on Amazon months later. He now sees little point in continuing the expense of buying and testing the products when the makers boldly list their ingredients. After Forbes picked up BSCG’s most recent report in last fall about the continuing availability of anabolic steroids on Amazon, the company again removed the products he’d highlighted.

I asked Catlin to check if Amazon has allowed the products back yet again. Sure enough, Amazon continues selling dangerous steroids and stimulants banned in sports and at least one drug regulated by the DEA, M-Drol, which contains the anabolic steroid methasterone. It is illegal to sell methasterone without a prescription and a DEA license. The DEA warned about methasterone in 2011, and this specific product has been recalled, yet it keeps making its way back onto Amazon. Amazon also trades in many compounds that are dangerous to the human body and banned by anti-doping agencies but aren’t yet illegal. One example is trenavar, marketed as TR3N, which is a “prohormone” that the body converts into another active compound. That compound is trenbolone, a DEA-controlled anabolic steroid. There’s nothing unusual about prodrugs as pharmaceuticals. We use many prescription prodrugs in daily medical practice, all regulated by the FDA, that become active only when processed inside the human body. That the DEA can’t easily regulate prodrugs of scheduled substances like trenbolone is simply an artifact of the outdated legislation that created the agency.

Screenshot

That’s a situation Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse and Orrin Hatch hope to change with the bipartisan Designer Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2014. The legislation promises to modernize the DEA’s governing rules by empowering it to respond to the exploding supplement industry, which has realized enormous profits by slightly tweaking controlled and prescription-only compounds to elude enforcement. These designer drugs are being marketed on outlets like Amazon before the DEA and FDA can react. “Right now, in order to classify new substances as steroids, the DEA must complete a burdensome and time-consuming series of chemical and pharmacological testing,” Sen. Whitehouse told me. He says the law would permit DEA to temporarily schedule new designer steroids as controlled substances, proactively protecting consumers from companies that are exploiting a loophole in current law.

Yet Amazon is already selling prescription drugs and at least one scheduled substance in violation of current laws. It’s unclear whether the new bill will do anything more than add to a growing list of unlawful commerce on the site, should it generate similar respect as current law. If the DEA and FDA only conduct flashy package intercepts like Operation Pangea, they won’t be doing much to stop the root problem, the Amazon marketplace itself. Yet unlike some of the fly-by-night companies federal agencies have targeted in the past, Amazon is listed on the NASDAQ. It has the capacity to reform its business model and operate on the straight and narrow.

The Center for Safe Internet Pharmacies represents a coalition of payment processors, shippers, and online service providers including Google, UPS, Visa, and MasterCard that all understand their platforms are being used for illegal pharmaceutical commerce. The organization believes that by banding together and sharing strategies to combat this criminal activity, they’re an important complement to the work of the FDA and DEA. The organization provides consumers a searchable database to check if a given website is a legal pharmacy. It shouldn’t surprise readers at this point that Amazon is not listed. The organization is proud of the fact that last year alone its member companies blocked or removed more than 5 million websites that illegally distribute prescription drugs, says Marjorie Clifton, CSIP’s executive director. “We want and invite companies like Amazon to join us,” Clifton says, adding that for Amazon to do so it will need to “sign on to a principles of participation document that outlines how our member companies interact in this space.” She wants Amazon to know that it is not alone in coming to terms with the fact that their platform is facilitating illegal drug sales. “All our partners have had to face this at one time or another.”

I asked Amazon public relations manager Erik Fairleigh a number of specific questions about how illegal products make it through to the site to end up being sold to Amazon customers. I wanted to know if Amazon employees manually review each product before it is listed, why products are removed following reporting like this only to reappear later on the site, and if Amazon considers itself protected from liability when third-party distributors are selling illegal products to Amazon’s customers. Fairleigh declined to answer these questions, but he did point me to Amazon’s policy on counterfeiting, which attempts to distance the company from the third-party sellers in its marketplace by saying “it is each seller’s responsibility to source and sell only authentic products.” The policy goes on to state that, “if we determine that a seller account has been used to engage in fraud or other illegal activity, remittances and payments may be withheld or forfeited.”

Thanks to work by people like Oliver Catlin, organizations like CSIP, and FDA actions against companies like BodyBuilding.com, Amazon is well aware that it operates a marketplace where illegal drugs are sold to American consumers. This report adds prescription antibiotics and muscle relaxants to the mix. The inaction of Amazon itself may be easier to explain than the inaction of federal regulators. As one of the first successful online businesses, Amazon had no qualms about exploiting a tax loophole that allowed it to sell goods for less than brick-and-mortar stores. It profits enormously from creating a platform for third-party sellers where anything that can be shipped can be sold, and Amazon will react after the fact by removing products or suspending sellers if there’s a serious problem. That strategy makes more sense for an auctioneer like eBay, where the seller handles the transaction, but Amazon’s sellers all have close business relationships with the company, which handles the customer relationship, processes all payments, and charges a percentage of sales that varies with the type of item.

In some cases, like TR3N, Amazon handles fulfillment as well, meaning this legal prodrug of an illegal steroid is shipped direct from an Amazon warehouse. Recently USA Today reported on Dutch research showing that another Amazon item, Dexaprine XR, causes vomiting, chest pain, and elevated heart rates that could be life-threatening due to its amphetamine-like ingredients. The manufacturer, iForce, pled criminally guilty in 2011 to putting synthetic steroids in its products. You won’t find this product at GNC, but Amazon gladly ships this poison out of its warehouse direct to your doorstep. Just because a product has escaped regulatory scrutiny so far doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to sell it or ingest it.

The blunt way Amazon wields its market dominance is well-known to publishers, especially Hachette. The literary world is up in arms about the way Amazon conducts its book selling business. A New Yorker editor recently tweeted that he made an online purchase via Walmart to “support the underdog.” But a far more serious consequence of the company’s power may be the way it has pushed out local shops run by people who knew what they were selling. Amazon has replaced that quaint notion with a robot-powered emporium that exposes American consumers to a world of dangerous products.