In case you missed it, Oct. 7–13 was designated Naturopathic Medicine Week, according to a Senate resolution sponsored by Sen. Barbara Mikulski and passed by the Senate with unanimous consent. Among the reasons the Senate cited:

- Naturopathic physicians can help address the shortage of primary care providers in the United States.

- The profession of naturopathic medicine is dedicated to providing health care to underserved populations.

- Naturopathic medicine provides consumers in the United States with more choice in health care.

Mikulski and the rest of the Senate may be surprised to learn that they were repeating 60-year-old justifications of Chinese medicine put forward by Chairman Mao. Unlike Mikulski, however, Mao was under no illusion that Chinese medicine—a key component of naturopathic education—actually worked. In The Private Life of Chairman Mao, Li Zhisui, one of Mao’s personal physicians, recounts a conversation they had on the subject. Trained as an M.D. in Western medicine, Li admitted to being baffled by ancient Chinese medical books, especially their theories relating to the five elements. It turns out his employer also found them implausible.

Photo by Leigh Vogel/Getty Images

“Even though I believe we should promote Chinese medicine,” Mao told him, “I personally do not believe in it. I don’t take Chinese medicine.”

Mao’s support of Chinese medicine was inspired by political necessity. In a 1950 speech (unwittingly echoed by the Senate’s concerns about “providing health care to underserved populations”), he said:

Our nation’s health work teams are large. They have to concern themselves with over 500 million people [including the] young, old, and ill. … At present, doctors of Western medicine are few, and thus the broad masses of the people, and in particular the peasants, rely on Chinese medicine to treat illness. Therefore, we must strive for the complete unification of Chinese medicine. (Translations from Kim Taylor’s Chinese Medicine in Early Communist China, 1945-1963: A Medicine of Revolution.)

For Mao, as for the Senate, health care policy also reflected national ideology. While the Senate resolution praised naturopathic medicine as providing “consumers” with “more choice” (does it get more American than that?), Mao emphasized “complete unification,” a grand dialectical Marxist synthesis of Chinese medicine and Western medicine. “This One Medicine,” exulted the president of the Chinese Medical Association in 1952, “will possess a basis in modern natural sciences, will have absorbed the ancient and the new, the Chinese and the foreign, all medical achievements—and will be China’s New Medicine!”

The target audience of this propagandized medical reform wasn’t just domestic. Thanks to Westerners’ starry-eyed romanticization of the mysterious Orient, Chinese medicine stood to improve international relations. A 1955 report from the Chinese Medical Association proudly declared:

Our ancient medicine is … the subject of interest of the medical world in capitalist countries. Soviet experts once especially invited Professor Li Tao to lecture on the history of Chinese medicine, but a delegation of French medical representatives [also] invited the two old Chinese medical practitioners Shi Jinmo and Yuan Hechai to a discussion. These are all evidence of the emphasis which foreign nations place on Chinese medicine.

But exporting Chinese medicine presented a formidable task, not least because there was no such thing as “Chinese medicine.” For thousands of years, healing practices in China had been highly idiosyncratic. Attempts at institutionalizing medical education were largely unsuccessful, and most practitioners drew at will on a mixture of demonology, astrology, yin-yang five phases theory, classic texts, folk wisdom, and personal experience.

Mao knew such medicine would be unappealing to empirically minded Westerners. He knew this because it was also unappealing to empirically minded Chinese people.

In 1923, Lu Xun, China’s most famous man of letters, reflected critically on his father’s visits to a Chinese doctor, visits that bankrupted the family and failed to produce results. “I still remember the doctor’s discussion and prescription,” Lu wrote, “and if I compare them with my knowledge now, I slowly realize that Chinese doctors are no more than a type of swindler, either intentional or unintentional, and I sympathize with deceived sick people and their families.”

Photo by einstraus/Flickr via Creative Commons

There are those who would blame Lu’s skepticism on the Western-style medical education he received in Japan. Rightfully wary of ethnocentrism, some scholars have suggested that negative judgments about Chinese medicine result from the misapplication of “Western” criticisms to “Eastern” thought. In the words of anthropologist Judith Farquhar: “The standards of argument by which we judge our own most rigorous explanations cannot be applied to Chinese medicine.”

But this produces an absurd picture of China as a mysterious place where logic doesn’t—and shouldn’t—apply. In truth, skepticism, empiricism, and logic are not uniquely Western, and we should feel free to apply them to Chinese medicine.

After all, that’s what Wang Qingren did during the Qing Dynasty when he wrote Correcting the Errors of Medical Literature. Wang’s work on the book began in 1797, when an epidemic broke out in his town and killed hundreds of children. The children were buried in shallow graves in a public cemetery, allowing stray dogs to dig them up and devour them, a custom thought to protect the next child in the family from premature death. On daily walks past the graveyard, Wang systematically studied the anatomy of the children’s corpses, discovering significant differences between what he saw and the content of Chinese classics.

And nearly 2,000 years ago, the philosopher Wang Chong mounted a devastating (and hilarious) critique of yin-yang five phases theory: “The horse is connected with wu (fire), the rat with zi (water). If water really conquers fire, [it would be much more convincing if] rats normally attacked horses and drove them away. Then the cock is connected with ya (metal) and the hare with mao (wood). If metal really conquers wood, why do cocks not devour hares?” (The translation of Wang Chong and the account of Wang Qingren come from Paul Unschuld’s Medicine in China: A History of Ideas.)

Mao understood he needed to deal with criticisms like those of Lu Xun, Wang Qingren, and Wang Chong in order for Chinese medicine to be taken seriously, both domestically and internationally. His solution was a two-pronged approach. First, inconsistent texts and idiosyncratic practices had to be standardized. Textbooks were written that portrayed Chinese medicine as a theoretical and practical whole, and they were taught in newly founded academies of so-called “traditional Chinese medicine,” a term that first appeared in English, not Chinese. Needless to say, the academies were anything but traditional, striving valiantly to “scientify” the teachings of classics that often contradicted one another and themselves. Terms such as “holism” (zhengtiguan) and “preventative care” (yufangxing) were used to provide the new system with appealing foundational principles, principles that are now standard fare in arguments about the benefits of alternative medicine. Mao would have been pleased to see how the Senate resolution paid homage to these innovations:

- Naturopathic medicine provides noninvasive, holistic treatments.

- Naturopathic medicine focuses on patient-centered care, the prevention of chronic illnesses, and early intervention in the treatment of chronic illnesses.

- Naturopathic physicians attend four-year, graduate-level programs that are accredited by agencies approved by the Department of Education.

The second part of Mao’s project was to provide Westerners with sensational evidence of Chinese medicine’s efficacy, particularly of acupuncture analgesia. The watershed moment was in 1971, when New York Times editor James Reston wrote an article entitled “Now, Let Me Tell You About My Appendectomy in Peking.” In it, he recounted how Wu Weiran of the Anti-Imperialist Hospital had administered “a standard injection of Xylocain and Bensocain” before removing his appendix. Later, while Reston recovered, acupuncture was used to relieve pain from post-operative gas. Eager to believe in mystical Eastern miracle workers, credulous Westerners misreported the story, claiming that acupuncture had been used as an anesthetic during Reston’s appendectomy, a falsehood that still has currency. Fascination with acupuncture exploded, allowing the Chinese Communist Party to put together a media blitz touting its extraordinary powers, complete with what appear to have been intentionally faked surgeries.

This deception was particularly impressive, given that acupuncture’s utility as a surgical analgesic should have been dubious for any historian of anesthesia or Chinese medicine. Hua Tuo, a legendary physician of the Han Dynasty, was famous for being the first person to perform surgery on an anesthetized patient. Yet despite expertise as an acupuncturist, Hua chose to anesthetize his patient (thankfully!) with what was likely a mixture of cannabis and wine. Similarly, the first modern recorded incidence of surgery using general anesthesia was a partial mastectomy performed by Japanese surgeon Hanaoka Seishu in 1804, who, while familiar with acupuncture, nevertheless followed in Hua’s footsteps and pursued pharmacological approaches to surgical pain relief.

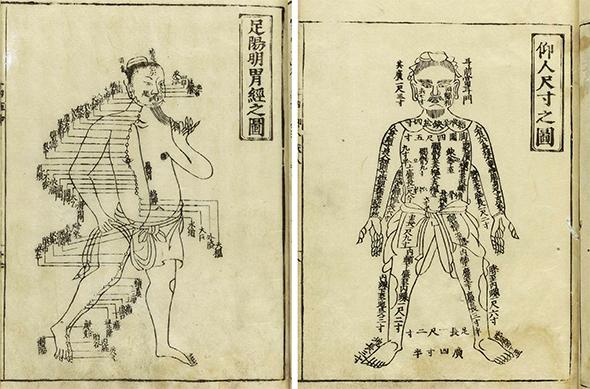

Images courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

No matter. The CCP’s propaganda served its purpose, effectively preying on the human desire for magical solutions to intractable problems. Even prominent scholars such as Joseph Needham were taken in by preposterous demonstrations of open-heart surgery performed with nothing but acupuncture as anesthesia—and, even more implausibly, without any form of artificial respiration. If Chinese medicine could perform one miracle, the public reasoned, surely many more would come: the cure for cancer, perhaps, or relief from “every type of chronic illness and digestive disorder, neurasthenia, swelling of the lower limbs and nervous pain of the fibula,” efficacy ascribed to a single acupuncture point by Ma Jixing in his 1954 book Advanced Teaching Materials for Chinese Medicine.

Photo by Shannon Stapleton/Reuters

Mao’s vision still reigns supreme, and the present state of misinformation about Chinese medicine is staggering, even in what appear to be trustworthy sources. Cancer.gov, for instance, states that “the oldest medical book known, written in China 4,000 years ago, describes the use of acupuncture to treat medical problems.” In fact, the oldest excavated Chinese medical text is no more than 2,300 years old and makes no mention of acupuncture at all—though it does include numerous exorcistic cures, a common element in ancient Chinese medicine that the popularizers of traditional Chinese medicine did well to forget. (Unfortunately, they did not forget about extracting bile from live bears, a practice easily justified by postulating the presence of qi, or life force, in living animals.)

None of this conclusively discredits Chinese medicine, just as L. Ron Hubbard’s previous career as a science fiction author doesn’t conclusively discredit Scientology. Some aspects of Chinese medicine are undeniably effective (a prominent American authority on Chinese medicine now heads up Harvard’s program in placebo studies), and some elements of Scientology are probably sound advice. Rather, what we learn from Mao is why some people who would scoff at Christian faith healing are still willing to defend the metaphysical basis of Chinese medicine. Both traditions assume the existence of undetectable causal phenomena—qi, in the case of Chinese medicine, and God’s power in the case of Christian Scientists. But mainstream secular philosophers speculate endlessly about whether “qi energy” will someday enjoy the status of once hypothetical entities such as genes and the Higgs boson, a possibility they are less likely to entertain about divine healing.

The reason so many people take Chinese medicine seriously, at least in part, is that it was reinvented by one of the most powerful propaganda machines of all time and then consciously marketed to a West disillusioned by its own spiritual traditions. The timing couldn’t have been better. Postmodernism was sweeping the academy, its valuable insights quickly degrading into naïve relativism. Thomas Kuhn had just published his theory of paradigm shifts and scientific revolutions, a brilliant (and controversial) analysis perennially abused by climate-change deniers and creation-scientists, who take him to have said that there’s no way to distinguish kooks from Galileo. Alan Watts was introducing hippies to mind-blowing Eastern philosophy; Joseph Campbell was preaching the power of myth. Sick of Christianity and guilty about past imperialist sins, the West was ready to be healed by Mao’s sanitized version of Chinese medicine.

Photo by Tom Mooring/Flickr via Creative Commons

Ultimately, however, the existence of qi, acupuncture meridians, and the Triple Energizer is no more inherently plausible than that of demons, the four humors, or the healing power of God. It’s just that Mao swindled us, taking advantage of a principle identified by G.K. Chesterton in 1925:

I am convinced that if we could tell the supernatural story of Christ word for word as of a Chinese hero, call him the Son of Heaven instead of the Son of God, and trace his rayed nimbus in the gold thread of Chinese embroideries or the gold lacquer of Chinese pottery, instead of in the gold leaf of our own old Catholic paintings, there would be a unanimous testimony to the spiritual purity of the story.

There is indeed a shortage of primary care providers in America, along with an appallingly large underserved population. But as Mao realized, solving such problems is a daunting task. In America it would require increased funding for medical care, unpopular regulation of the medical industry, and substantive lifestyle changes. It’s easier to believe in miracles, panaceas, and natural healing powers. Nowadays one of the most popular alternative solutions, enshrined in the Senate resolution, is a gift from Chairman Mao.