When I worked in finance, I had a generous health plan. Now I can’t afford to pay the state-subsidized annual insurance premium of $6,924 (six months’ rent) myself. Despite my good health, my appendix could become inflamed at any time. Appendix removal surgery costs an average of $33,000 (house down payment). Any medical problem that can’t be fixed with a pill could bankrupt me.

My friend Tikka exposed me to a more frugal solution. Tikka spends his days and limited money traveling Asia by foot or bicycle, and when he got a hernia, he flew to India to have it repaired. There he paid $300 (groceries for a month) for a surgery that would cost $29,880 (six acres of farmland) here. He was a medical tourist—a patient who travels abroad for cost-effective treatment for cancer, cosmetic surgery, or any large yet time-insensitive medical need. Some people travel to Belgium for hip replacement surgery, for example, because the same implant that is sold for $4,000 in Belgium can go for as much as $39,000 here. The savings are significant enough that U.S. citizens are willing to brave unfamiliar hospitals and recuperate from serious procedures away from their family and friends.

Of course, for some Americans, discounted foreign medical care is available close to home. San Diego residents can drive 20 minutes to Tijuana, Mexico, for 60 percent off tummy tucks and cheap dental crowns. Some cross the border nursing broken bones. If the rest of the country were just an hour away from more affordable international care instead of a day’s flight from it, medical tourism would be feasible for not only time-insensitive health problems, but for emergencies and minor procedures, too.

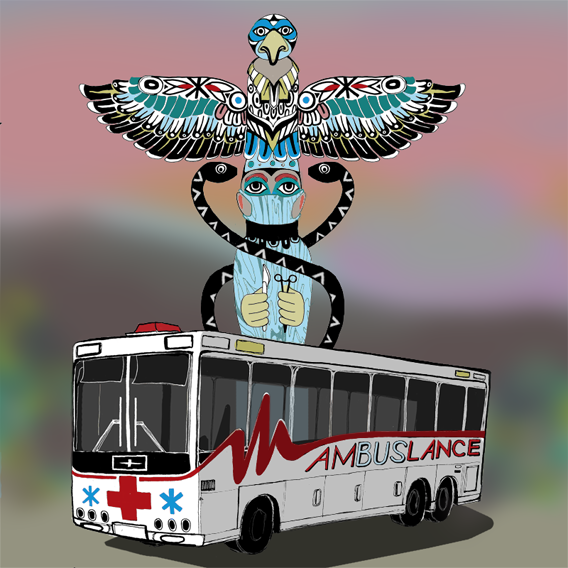

So here’s a proposal: What if those Indian doctors came to us? Foreign doctors can’t operate on U.S. soil without extensive recertification, but they can work in any country that transfers their qualifications. Doctors from India already work abroad in the Middle East; they treat Qataris and Kuwaitis for a fraction of what these patients would have to pay here. What if some of those doctors set up shop in our nearest semi-autonomous states: Native American reservations, some of which already administer their own health care programs. The Mohegan tribe, for example, is only 128 miles from New York City.

This free-market solution, which the Republican-controlled House should love, requires no changes to our existing state or federal law. The government needs only to stay out of the way of the Asian-Indian-run medical facilities on American-Indian reservations. Buses would leave from Chinatown. Nurses would triage patients at the bus-ticket counter and assign appointment times as they boarded. For more urgent cases, the patients could dial 777-7777 and pay the $278 livery car fare (the cost of a Barbie Jeep), which is still cheaper than an across-town ambulance ride at $704 (1988 Jeep). The three-hour ride might be uncomfortable, but the savings would make the journey worth it. Poorer citizens would rejoice: affordable care at last.

Surely a few people would die on the 128-mile drive. Yet President Obama could in good faith dismiss the few unfortunate deaths en route as the cost of business of bringing affordable health care to the 48.6 million uninsured Americans. The physician and hospital associations would complain that people were receiving poor care. Such interest groups would likely file lawsuits challenging the American Indians’ autonomy and ability to determine their own medical systems. These challengers would explain that they are only thinking about their patients, and they wouldn’t be lying. They just wouldn’t appreciate that the poor and middle class aren’t their patients. They cannot afford to be. They just don’t have $29,880 (a year’s college tuition) to patch up their hernias.

I can’t afford to be their patient. Last year, when a marble-sized lump beside my shoulder blade grew to the size of a plump grape, I called a dermatologist. “Diagnosis is $150 (7 ounces of silver),” he said. He then explained that the diagnosis fee is discounted from what he’d charge for a sebaceous cyst removal: $3,000 (Tiffany 18-karat gold and diamond ring).

I decided to do it myself. While amateur self-surgery on your own back may sound difficult, it looked easy on YouTube. The video-surgeon only took four minutes and 53 seconds to make one clean incision. I understood scarring was likely and an infection was possible. But taping the wound closed with butterfly strips and disinfecting my equipment would probably prevent complications. I sanitized a new razor blade with rubbing alcohol, took a shower, and scrubbed my back. I enlisted my wife and she sliced it out.

A month later my wound has healed nicely and the bulge on my back is gone. The scar is larger than it might have been had a doctor sewn it up. Overall the experience wasn’t bad, but I would have preferred a skilled hand. The nationality of that hand wouldn’t matter. I checked: The price for cyst removal in Mumbai is only $50 (my account balance).