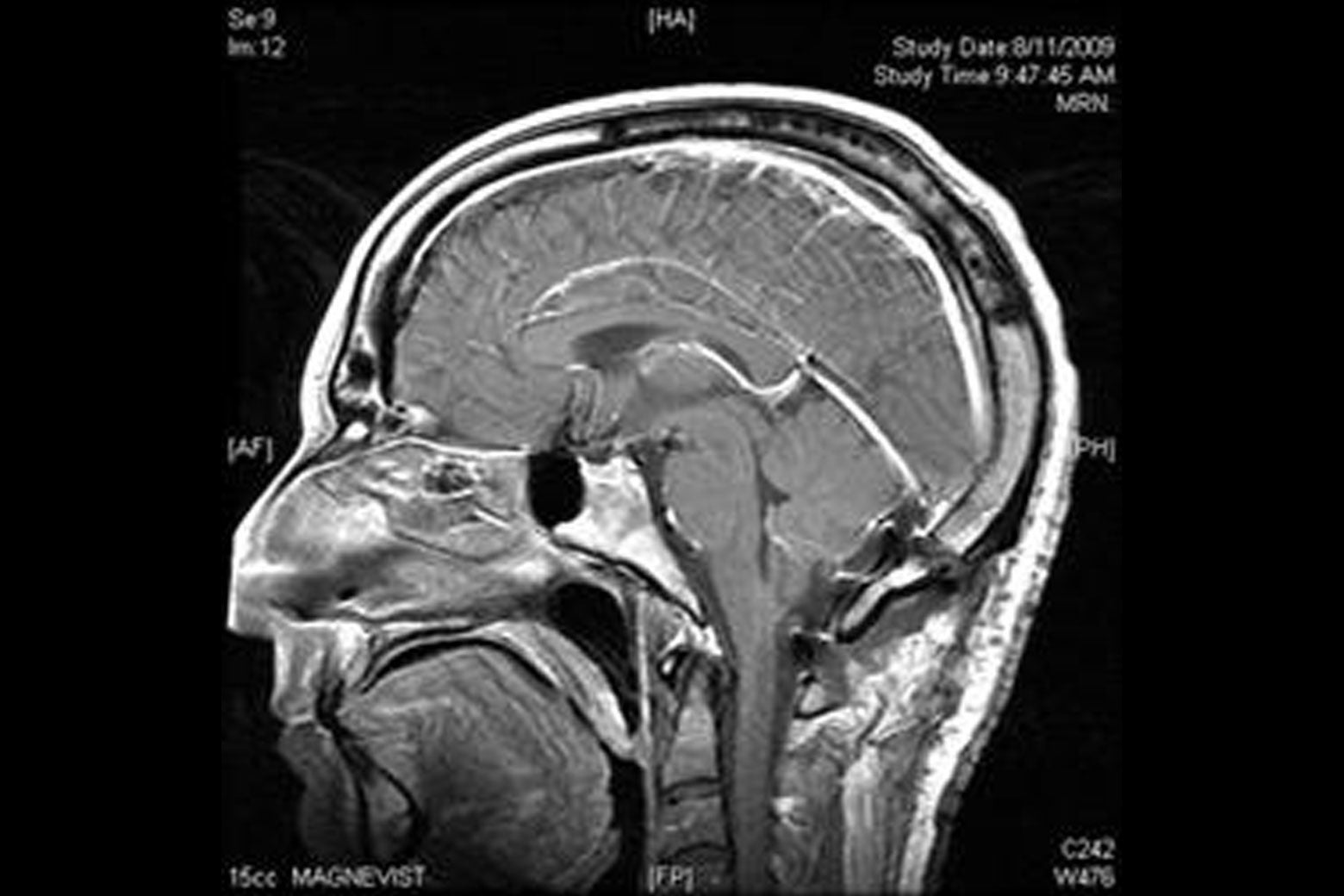

I used to consider brain tumors a misfortune that befell other people, like typhoons or train wrecks. But in early July, I underwent a routine MRI, ordered as part of a minor eye procedure, that uncovered the presence of a 2-centimeter “suspicious hyperdense lesion” in a small, fluid-filled nook behind my cerebellum, nudged against my brain stem like a cranial house cat. It’s unrelated to my ocular problem, and I’m completely asymptomatic, so in the argot of radiology, the finding was “incidental.” To me, it was anything but.

Is this shocking diagnosis an early blessing in disguise or a worrisome red herring? It depends whom you ask. The doctors think the tumor, located at the floor of my fourth ventricle, is either a choroid plexus papilloma or an ependymoma. The latter is worse, but thankfully both tend to be slow-growing and benign; of course, tend to leaves open the frightening possibility of malignancy. And even benign tumors can do serious damage, especially in the cramped spot where mine is. Unfortunately, pathology and potential for harm can be determined only by removing the mass, which requires a pedigreed surgeon to drill a hole in my skull and poke around inside.

At the moment, the tumor isn’t causing any functional issues. I feel great, and my only awareness of it is courtesy of grainy film images. (Tumors are like a Bigfoot sighting in this way.) I won’t die from it—not this baseball season, anyway. But what about a year from now? Or five? In 2029? The best answer I’ve received is that there is no certain answer at all.

The vagueness is troubling. It might grow, or it might stay the same size. It might be new, or it might have been there since my birth. It might someday block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (which leads to hydrocephalus and, eventually, death), or it might not. The most troubling aspect is the tumor’s proximity to my brain stem, through which sensory and motor-skill nerve connections pass to the rest of the body. But here again the neurosurgeons are operating in—forgive the pun—a gray area. MRIs provide many miraculous views of the brain, but they cannot peer upward from the direction of the chin toward the scalp, making it impossible to determine whether this valuable real estate has been invaded by the tumor. There are only best guesses, which often feel downright lousy.

As a result, every potential prognosis is theoretical, leaving me to decide whether to operate now or sit tight while monitoring the tumor’s development, as if it were a tropical storm with the potential to make landfall. The former requires suiting up for a suboccipital craniotomy to correct a problem I can’t feel. Is it advisable to undertake something so risky, psychologically terrifying, and difficult to recover from in order to correct what may become a problem? That’s to say nothing of the costs that surgeries of this nature place on our shaky trillion-dollar health care system—including diagnostic testing, the surgeon’s fee, anesthesia, and the hospital stay, this will likely be a $100,000-plus procedure. Conversely, the wait-and-see approach means living with the knowledge that the other shoe may drop with a terrific boom.

As one neurosurgeon with the bedside manner of a casino pit boss told me, “I’d want this tumor to really declare itself before I went in.” I wanted to sock him in the nose, since “declaration” would take the form of intense migraines, seizures, and brain-bruising intracranial pressure. On the other hand, while I’m lucky to be symptom-free, pain would at least make surgery a form of relief and thus an easier call.

This quandary is troubling but, in the age of the over-testing and ever-improving diagnostic technologies, increasingly common. Studies suggest that early screening doesn’t save near enough lives to justify the costs. (The most noteworthy recent example is prostate cancer.) Yet those who can afford them clamor for pricey “executive physicals” at blue-chip institutions like the Mayo Clinic for two days of intensive examination. Scan your entire body and you’re likely to find something. But the anxiety created by awareness is often worse than the maladies that are discovered.

So what is the best course for an otherwise healthy, asymptomatic 41-year-old white male with a posterior fossa brain tumor? It varies. Of the five doctors who weighed in on my case, even the four who felt certain that I should do the procedure now were careful to hedge. Each cautioned that this wasn’t an emergency (though it feels urgent to me), and none of these board-certified men of steel would do the thing I desperately wanted them to: tell me that I had no choice. Where was the arrogant sureness that comes of years of rigorous training? How could these know-it-alls leave the decision in the hands of a humanities major barely able to apply a styptic pencil?

I turned the process into a journalistic distraction, showing up to doctor’s appointments with four pages of typewritten questions, a digital recorder, and a backup stenographer in the form of my anxious but strong wife. I interviewed brain surgery survivors and read obscure neurosurgical journals from Turkey. I tried to divine confidence from the fact that brain surgery (in the form of trepanning) dates to 7000 B.C. and that the first successful brain-tumor excision was performed by a Scottish surgeon in 1879, a year before Thomas Edison was granted a patent for the incandescent light bulb. I even waded into the messy world of brain-tumor chat rooms, which left me feeling relatively fortunate (and sane). The more I learned, the less scary it all became. But anatomical charts and WebMD entries couldn’t make the decision for me.

The tumor episode’s darkest hour came the night I sat up pondering the letter I would write to my 13-month-old son, Nathaniel, to be read when he reached whatever age is appropriate for a boy to memorialize his late father. The next morning I decided that taking risky, possibly unnecessary action was better than doing nothing. I owed my family the opportunity to avert future catastrophe along with the gnawing uncertainty that accompanies waiting for bad news.

Allowing myself to be scared made me realize that I’m not a person who can live with a tumor in his head, benign or otherwise. If the world breaks down into two types, I’m in the camp that would prefer not to learn what hydrocephalus feels like, even if that means a difficult operation and months of recovery. If I don’t do it, I’ll ascribe every ache and pain to the massive tumor no doubt swallowing my brain.

It’s never a great time to have your noggin cut open by a Harvard man, but avoiding it won’t make the procedure any easier in the future, though it could make it harder. Coming to this decision has provided welcome relief, though I still have to face the knife. More importantly, it has freed up mental space for the really important choices, like whether to shave my head Travis Bickle-style before I do this and what my first recovery room wisecrack will be. It’s a tossup between “Actually, it was brain surgery” and “I needed that like I need a hole in the head.”

The preceding was written while I still had a brain tumor. On Aug. 10, my wife and I drove to New York Presbyterian Hospital at dawn. As with international travel, I was ordered to arrive three hours before departure. Just before 8:30 a.m., I was wheeled into an operating room by a gray-haired orderly who assured me Jesus would be watching. I was happy to have the extra attention.

The last thing I recall is signing the consent forms, though my surgeon insists that I asked about the vacation from which he’d just returned. Six hours later, he informed my family that the surgery had been a success: They removed the entire tumor, it did not involve the brain stem, and it appeared to have been a benign choroid plexus papilloma (which was later confirmed via a formal pathology).

I’d been cured.

My first night was a fever dream of blunt head pain, monitor beeps, distant screams, a parched throat, and the numbing effects of an opioid 10 times stronger than morphine. But three evenings later I was home, having spent fewer than 85 hours at the hospital. Based on what I witnessed during my brief stay in the neurological ward, I made it out relatively unscathed.

As I continue my recovery, I’m baffled by how normal I have felt. There is minor residual pain, and I’m still aware of the 5-inch scar (which bisects the back of my head from the neckline to the crown and looked, with the stitches, like a deflated football), but it’ll soon be covered by hair. And while I’m not quite back to fighting form, my brain feels exactly as it did before the operation. I have, in other words, the same unremarkable mind I started with, albeit one that appreciates life a little more.

So did I make the right decision? Given the near perfect outcome (and the fact that I’m fortunate enough to have health care coverage), absolutely. In my view I was going to have to deal with this at some point, and I chose not to wait until it was made more difficult by growth. While there is a very remote chance the tumor might never have changed in size, I did not undergo voluntary brain surgery. I simply happened to have a half-day craniotomy and tumor removal at a moment when the circumstances were favorable. There’s no better time to do something as complicated as brain surgery.