Forty percent of Americans are evangelical Christians, and many of them reject evolution. Jeff Hardin, chairman of the University of Wisconsin’s zoology department, takes this personally. Hardin is an evangelical, but much of his evangelism is directed at his fellow believers. He wants to persuade them that evolution and Christianity are compatible.

Hardin didn’t grow up in a Christian household. His father was an engineer. As an adolescent, Hardin had a religious experience and joined a church. Christianity spoke to his heart, but it didn’t change the love of science he had learned from his dad. When Hardin became a biologist and met students who thought they had to choose between faith and science, it tore him apart. He wanted to help them stay whole.

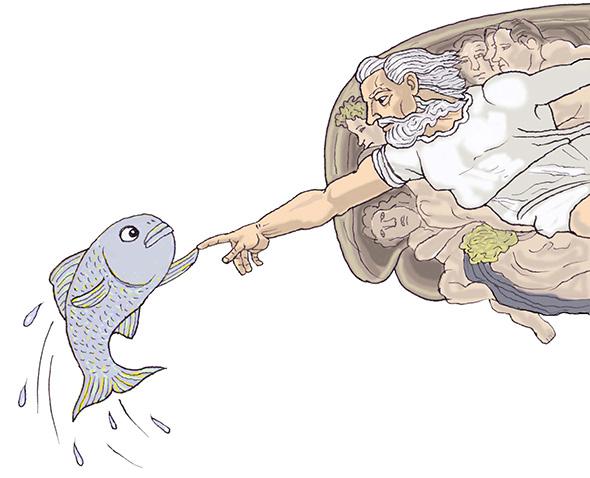

Today, Hardin speaks for an emerging school of Christian thinkers. They call themselves evolutionary creationists. They believe that God authored the emergence of life and humankind but that evolution explains how this process unfolded. They accept what science has established: The Earth is billions of years old, and all species, including ours, have evolved from other species.

Hardin understands why many Christians recoil from evolution. But to believe in a young Earth, he says, you have to reject so much science that you can’t do research in related fields. “Intelligent design” tries to be more sophisticated, but you can’t build science around it, because it makes no testable predictions.

To learn and work in science, Hardin says, you have to follow its rules. Those rules are limited—they govern laboratories, not love—but they’re spectacularly successful. One of the rules is often called methodological naturalism. At a Faith Angle Forum last month, Hardin explained what this means: In science, you can’t make supernatural claims. That’s because supernatural causes aren’t repeatable. You can believe that God parted the Red Sea, but you can’t test that process experimentally or use it to predict the behavior of other bodies of water.

That doesn’t mean science explains everything. Hardin distinguishes methodological naturalism from metaphysical naturalism, which denies the existence of the supernatural. The two ideas are often confused. Hardin wants to clarify the differences and calm evangelicals’ anxiety about the scope of science. He wants Christians to understand that mainstream science is theologically safe.

Hardin’s first message to believers is that they don’t have to choose between mechanical explanation and teleology, the idea that things work toward a goal. You can recognize the ruthless dynamics of evolution, as Hardin does, while maintaining that it follows a divine plan. “God created the world with the intention that we would be here and that we would one day be capable of interacting with him,” says Hardin. To illustrate this paradox, he cites Proverbs 16: “The lot is cast into the lap, but its every decision is from the Lord.” Each natural event seems random, but the overall pattern advances a purpose.

Second, Hardin wants evangelicals to trust God. If God made the world, they shouldn’t be afraid to see his creation as it is. Hardin approaches science with serene faith. He believes that the evidence he encounters—what Francis Bacon called the “Book of God’s Works”—will be compatible with the Bible.

Hardin recognizes, crucially, that when the two books don’t seem to match, the error might be in his own understanding of the Bible. Rather than reject what science has discovered, he asks how Scripture can be understood better so that it fits the scientific evidence.

This requires humility. “Truth and absolute certitude are not the same,” says Hardin. The proper Christian attitude is that truth resides in Jesus. The believer’s job is to follow Jesus, not to assume that the believer knows the route. Hardin cites the Apostle Paul’s counsel that God “works in you to will and to act in order to fulfill his good purpose.” One way God works in people is through science. They learn that their initial conclusions from Scripture—computing the age of humanity, for example, from the number of generations recounted since Adam—are clumsy and naive. To allow God to work in them, Christians must remain, in Hardin’s words, “epistemically open.”

Christians who believe that the world was created in six days, or that the Earth is only a few thousand years old, think they’re reading the Bible literally. But in reality, they’re projecting modern notions of time and narration onto their ancestors. Hardin shares their aspiration to be faithful to the Bible, but he argues that to achieve this, one must approach the text the way one approaches science: with empirical rigor. Scripture is a real thing. It was written and preached for a lay audience in a historical context. Those people weren’t scientists or journalists. So it makes no sense to treat the text as a tight chronology, nailing down timelines or the process of speciation. Instead, evolutionary creationists advocate what Hardin calls “literary-cultural analysis”—asking, in layman’s terms, what each passage was meant to convey to an ancient Hebrew.

Take the story of Adam and Eve. The standard interpretation is that God miraculously created this couple, and the rest of us descended from them. But that account runs into problems: for instance, the genetic evidence that the population of Homo sapiens was never smaller than 10,000. Evolutionary creationists such as National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins and Cambridge molecular biologist Denis Alexander believe there are ways to reconcile the Bible with the data. One option is that Adam and Eve, while not the first humans, were progenitors of the people whose stories are told in Genesis. As for the biblical description of Adam’s creation—“God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life”— ancient Hebrews wouldn’t have read this as a recipe. The message is simply that God made us.

Hardin asks atheists to be humble about what science can tell us. In his view, it can’t resolve whether God exists. But at the same time, he asks Christians to be humble about what science can’t tell us. When creationists use God to explain gaps in scientific knowledge, such as the development of “irreducibly complex” traits, Hardin points out that science has often left gaps that were later filled in. Adjustments in planetary orbits, which Newton attributed to God, turned out to be explicable by interplanetary gravity.

There’s plenty of wisdom in what Hardin says. But for many Christians, the messenger is more important. They listen to Hardin because he’s one of them. He’s family. Ultimately, what he wants to cultivate isn’t a theory of human origins, but a way of thinking. “I want to be a self-critical reader of the Scriptures,” he says. Students who learn the right habits—humility, perspective, epistemic openness—won’t just become better scientists. They’ll become better people.

You can read Jeff Hardin’s remarks at the November 2014 Faith Angle Forum here. Or you can listen to the audio here. The Ethics and Public Policy Center has also posted audio of his responses to questions (part 1, part 2, and part 3) as well as his slide presentation on science and evolutionary creationism.