One of the juiciest, most heated, and ultimately most productive rivalries in the recent history of science was the race to sequence the human genome. On one side was a methodical, massive, publicly funded international project managed by the National Institutes of Health. On the other side was a lean, speedy, profit-driven company run by a brash scientist who came up with a method for sequencing DNA that ran circles around the NIH technique. The public consortium, led by Francis Collins, now head of the National Institutes of Health, criticized the company, Celera, for trying to turn a profit off the genome. J. Craig Venter, who ran Celera, had quit the public effort in frustration at its slow pace. His company’s slogan was “Speed Matters.” Members of the two teams despised one another. It was delicious.

Self-interest trumped rivalry for a brief time in June 2000, when the two teams called a truce and shook hands at a White House ceremony. They announced that they each had a working draft of the human genome and would soon publish their independent sequence maps jointly and reveal what they had discovered about life’s code.

The peace ended a few weeks later as they raced to piece together their sequences. The public consortium tried to prevent Science from publishing Celera’s genome over questions of how the data would be made available. (Disclosure: I worked for Science’s news department at the time.) And its scientists spent the days leading up to publication telling science reporters that Celera’s method had failed. (It hadn’t.)

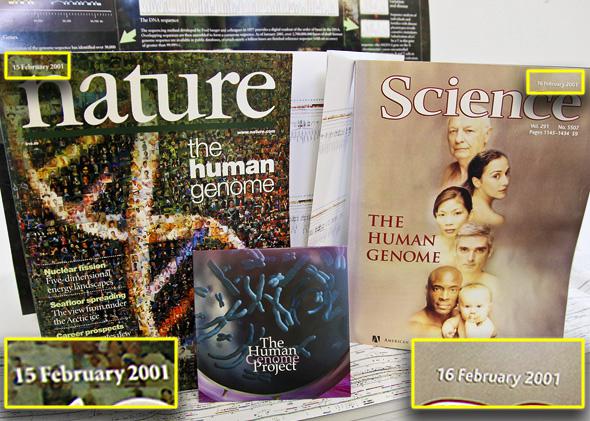

After an exhausting final sprint by thousands of scientists, the two sequences of the human genome were revealed to the world on Feb. 12, 2001, to great acclaim, in Science and Nature (themselves archrivals). There were press conferences and celebrations and headlines around the world. The New York Times said the publications opened “a new era in human biology and medicine.” Eric Lander, one of the leaders of the public consortium, said, “We are standing at an extraordinary moment in scientific history. It’s as though we have climbed to the top of the Himalayas. We can for the first time see the breathtaking vista of the human genome.” Collins wrote that “the publications in February 2001 carried with them the kind of satisfying scientific significance that laborers in the genome fields had longed for.” He told Science, “There’s a long list of things that blew my socks off,” such as the unexpectedly low number of genes. Venter, still reeling over the concerted effort to discredit his genome, told the New York Times, “If we weren’t resistant and somewhat defiant this never would have gotten done,” and Don Kennedy, editor of Science, told the paper, “There is no doubt the world is getting [the human genome sequence] well before it otherwise would have if Venter had not entered the race.”

The genome sequences were accompanied in Science and Nature by dozens of analysis papers each from the two teams, wall-size posters of human chromosomes with their genetic sequences spelled out, timelines, and CD-ROMs. Scientists celebrated with Champagne, teary speeches, and blowout parties, including one at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. Francis Collins was there: He performed onstage with his band. (They were called the Directors because the band members all directed NIH divisions, and everybody played lead guitar.) That date, again, was February 2001.

So why in the world are the National Institutes of Health and the Smithsonian Institution celebrating the 10th anniversary of the sequencing of the human genome this year?

They didn’t miss a deadline or mess up the math. By designating 2003 as the year the genome was sequenced, the NIH is still fighting against Celera. It’s laying exclusive claim for credit and trying to push its rival out of the history books. It’s trying to give the leaders of the public consortium an edge in the battle for the inevitable Nobel Prize.The Celera genome paper had more than 200 authors, and the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium’s paper listed more than 300, from 25 institutions. The Nobel Prize can be split only three ways.

In 2001 both teams clearly acknowledged that their sequences were first drafts. The maps had some gaps and fuzzy bits, but the main structure was known. Scientists could tally genes and place them in the correct positions on chromosomes. The two teams proved that their techniques for assembling 3 billion base pairs could work. They compared the human genomes with the genomes of other species. (We’re much more mouselike than anyone anticipated.)

After the dueling sequences were published, Celera shifted its focus from genome sequencing to drug development. The public consortium spiffed up its sequence and published the “complete” human genome in Nature in April 2003. This publication didn’t get a lot of attention, and it didn’t make major changes to the analyses from 2001.

I asked the National Human Genome Research Institute why it celebrated 2003 rather than 2001, and a spokesman replied (emphasis mine): “This is because 2003 marked the final release of the genome sequence, and the research the institute does now is widely based off of it. You’re right by saying that the 2001 papers were extremely important and groundbreaking, but 2003 marks the year that the Human Genome Project was completed and the completed genome sequence was released. There was still a little more research to be done to complete the sequence after the 2001 sequence was released.”

The NIH has been hosting anniversary events all year, but the most galling anniversary claim is made in an exhibit that opened this year at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, the second-most-visited museum in the world. (Dang that Louvre.) It’s called “Genome: Unlocking Life’s Code,” and the promotional materials claim, “It took nearly a decade, three billion dollars, and thousands of scientists to sequence the human genome in 2003.” (Disclosure: I worked for Smithsonian magazine while the exhibition, produced in partnership with the NIH, was being planned, and I consulted very informally with the curators. That is, we had lunch and I warned them they were being played.) To be clear, I’m delighted that the Smithsonian has an exhibit on the human genome. And I’m a huge fan of the NIH. (To its credit, the NIH did host an anniversary symposium in 2011.) But the Smithsonian exhibit enshrines the 2003 date in the country’s museum of record and minimizes the great drama and triumph of 2001.

Celebrating 2003 rather than 2001 as the most important date in the sequencing of the human genome is like celebrating the anniversary of the final Apollo mission rather than the first one to land on the moon. Just this once, don’t listen to the NIH. Remember the thrills and rivalries and breathtaking accomplishments of 2001. And happy 12th anniversary of the sequencing of the human genome.