People may vote with their pocketbooks, but more often than not, they revolt with their bellies. If you want to predict where political instability, revolution, coups d’etat, or interstate warfare will occur, the best factor to keep an eye on is not GDP, the human development index, or energy prices.

“If I were to pick a single indicator—economic, political, social—that I think will tell us more than any other, it would be the price of grain,” says Lester Brown, president of the Earth Policy Institute, who has been writing about the politics and economics of food since the 1950s.

Food, of course, is never the sole driver of instability or uprising. Corruption, a lack of democracy, ethnic tension—these better known factors may be critical—but food is often the difference between an unhappy but quiescent population and one in revolt.

Take Venezuela, where a toxic combination of gas subsidies, currency controls, and hoarding have led to chronic food shortages—a major factor motivating the anti-government protests that have wracked the country since the beginning of this year.

It’s not always high prices that are to blame. Behind the ongoing protests against Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra in Thailand, in addition to concerns over corruption and a debate on the future of the country’s democracy, is a probe over a controversial rice-hoarding scheme that has led to a global glut.

This idea isn’t exactly new. “We’ve known since the times of the Roman poet Juvenal”—he of bread and circuses fame—“that food is an inherently political commodity,” says Cullen Hendrix, a political scientist at the University of Denver’s Korbel School of International Relations and a leading authority on the relationship between food and conflict.

Two events have renewed interest among scholars in the relationship between food prices and political instability. The first was the 2007–08 food crisis, which triggered food riots in countries from Haiti to Bangladesh to Mozambique.

The second was the Arab Spring, the first signs of which were riots in response to high food prices in Algeria and Tunisia. The revolutions that swept the Middle East that year were, of course, primarily the result of a population frustrated by decades of dictatorship and corruption, but according to Hendrix, Egypt’s revolution, in particular, is impossible to fully understand without taking into account the role of food.

Autocratic governments have a habit of keeping food and fuel prices artificially low through subsidies and price controls. As Hendrix puts it, “Rational leaders have an incentive to cater to the preferences of urbanites. They are closer to the center of power, they face lower costs for collective action, they live in dense environments in which protests are particularly threatening to a leader. So what do these urbanites want? They want cheap food.”

If you’re the dictator of a small, rich country, you can theoretically feed your population indefinitely. In 2011, for instance, while revolutions were sweeping the region, oil-rich Kuwait announced that it would commemorate the anniversary of the country’s liberation from Iraq by giving every citizen a grant of 1,000 dinars ($3,545) and free food for 13 months. The message to citizens was pretty clear.

Egypt is the most populous country in the Arab world and is not blessed with a significant amount of arable land or oil reserves; its rulers don’t have options like Kuwait’s. Egypt has a history of food-based instability. In 1977, under pressure from the World Bank, Anwar Sadat severely curtailed food subsidies. In the resulting “bread intifada,” strikes and rioting lasted for two days and around 800 people were killed.

By 2011, food and fuel subsidies accounted for a staggering 8 percent of Egypt’s GDP. Hosni Mubarak’s government could no longer afford to feed his population into submission. Even with subsidies, grain prices jumped 30 percent in Egypt between 2010 and 2011, and the uprising began in January 2011.

The Arab Spring may become the textbook example of the geopolitics of food prices—the food riots and subsequent revolutions transfixed the world. But shifts in food price may be responsible for an even more profound reordering of global power. Food may explain why everything changed during the 1980s.

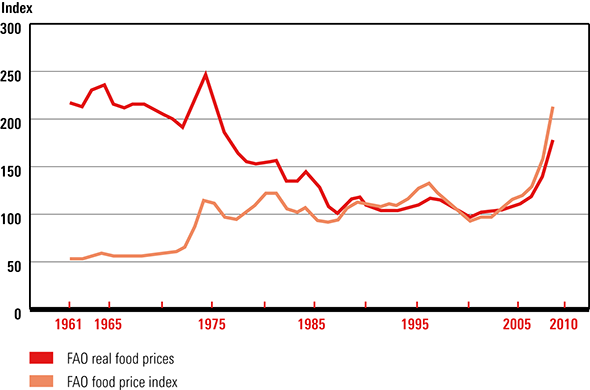

After a price shock in the late 1970s, food prices underwent a slump during the early and mid-1980s. A confluence of factors included slowing economic growth; the spread of the “green revolution,” which improved the efficiency of agriculture in developing countries; and the falling price of oil.

This slump played a role in many of the larger geopolitical trends of the era, according to Argentinian economist Eugenio Diaz-Bonilla. The Soviet Union, which was a net exporter of commodities, was hit hard economically, and by the end of the decade was near collapse. Growth was sluggish throughout the decade in Latin America, where most economies are based on agriculture. Dictatorships were overthrown in Ecuador, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Chile. African countries entered a period of economic stagnation and civil strife that the continent only recently started to recover from. The emerging tigers of East Asia, meanwhile, such as China and South Korea, benefited from low prices on the food they import.

In the 1990s, food prices began to rise and have continued increasing ever since, with the exception of a brief blip during the global economic crisis in the late 2000s. Overall, the food price index as measured by the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization is twice what it was in 1991. There’s little to suggest they’re going to fall any time soon.

Brown argues that today’s high prices are fundamentally different than spikes of the past. For one thing, demand is being driven today less by growing populations than by an increasing number of a people “moving up the food chain,” adopting middle-class lifestyles with middle-class diets, including more meat and dairy. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the global middle class will grow from 1.8 billion people in 2009 to 3.2 billion by 2020 and 4.9 billion by 2030. That’s great news for human well-being, but it will inevitably put pressure on food supplies. (The average American currently eats 50 percent more calories per day than the average Indian.)

Then there’s the fact that we seem to have maxed out the amount of food we can grow on the land we’re currently cultivating. Corn yields per acre in the United States, for instance, haven’t gone up significantly since the mid-2000s. Rice yields in China have flat-lined for longer than that. Barring another technological breakthrough on the level of the green revolution or a global economic collapse, we may be stuck with the food supply we’ve got for the foreseeable future.

Global warming complicates the food picture by both disrupting growing seasons and exacerbating water shortages. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change addresses the issue of food security specifically, predicting that “Global temperature increases of 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit or more above late-20th-century levels, combined with increasing food demand, would pose large risks to food security globally and regionally.”

So what does a world of permanently expensive food mean for global politics? Likely a lot more global instability in countries that are already among the world’s conflict hotspots. As a recent World Food Program report, co-authored by Hendrix, points out, “Sixty-five percent of the world’s food-insecure people live in seven countries: India, China, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Ethiopia, of which all but China have experienced civil conflict in the past decade, with DRC, Ethiopia, India, and Pakistan currently embroiled in civil conflicts.” And China, it should be pointed out, hasn’t been all that quiet. With about 180,000 protests per year, the government now spends about $125 billion annually on riot control.

China’s growing demand for food is a political issue not just for Beijing but for other governments as well. For years, the Chinese Communist Party has maintained an ideological commitment to grain self-sufficiency, a policy it has only recently begun to back away from—a shift that affects markets around the world.

China has also been at the forefront of the trend of buying large tracts of land in developing countries to meet demand for grain back home, a practice denounced by critics as “land grabs.” State-connected Chinese firms have purchased a swath of farmland the size of Luxembourg in Argentina as well as about 5 percent of Ukraine’s territory.

Purchases on this scale bring up obvious concerns over sovereignty. Anger over the purchase of half of Madagascar’s arable land by the South Korean conglomerate Daewoo was a major precipitating factor in the overthrow of Madagascar’s government in 2009.

Asked what countries might be sites of food-driven insecurity in the near future, Brown points to Nigeria, a nation roughly the size of Texas that could have more people than the United States by 2050. Nigeria has ample farmland, but like most countries in West Africa, it imports most of the food it consumes, making it extremely sensitive to global price fluctuations. Attempts to cut the country’s longstanding fuel subsidies have sparked riots, and a steep change in food prices could do the same.

In general, countries in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa will likely be most sensitive to food insecurity. Food shortage and conflict can also be mutually reinforcing, as in the war-torn Central African Republic where prices in stores have skyrocketed in recent weeks after Muslim shopkeepers fled ethnic violence.

If there’s a winner in a world of scarce and expensive food, it’s likely to be the United States. America is the world’s undisputed food superpower, the Saudi Arabia of grain. Brown notes that Iowa alone grows more grain than all of Canada*. The United States as a whole grows more soybeans than China. And due to generous federal subsidies for ethanol, the United States isn’t even growing nearly the amount of food it could. Forty percent of our corn is going into fuel.

Yes, we’re likely to see shortage of imported foods like avocados and limes, and droughts and erratic weather will continue to drive price fluctuations, but the United States is still likely to be one of the last countries to experience the consequences of a hungry planet—and it will be the source of a significant amount of the rest of the world’s food.

Of course, in the long term, a world where an increasing number of people are facing foodless days and an increasing number of countries are facing food-driven instability could be dangerous for everyone.

Correction, April 9, 2014: This article originally misstated that Lester Brown noted that Iowa alone grows more wheat than all of Canada. He noted that Iowa grows more grain than Canada. (Return.)